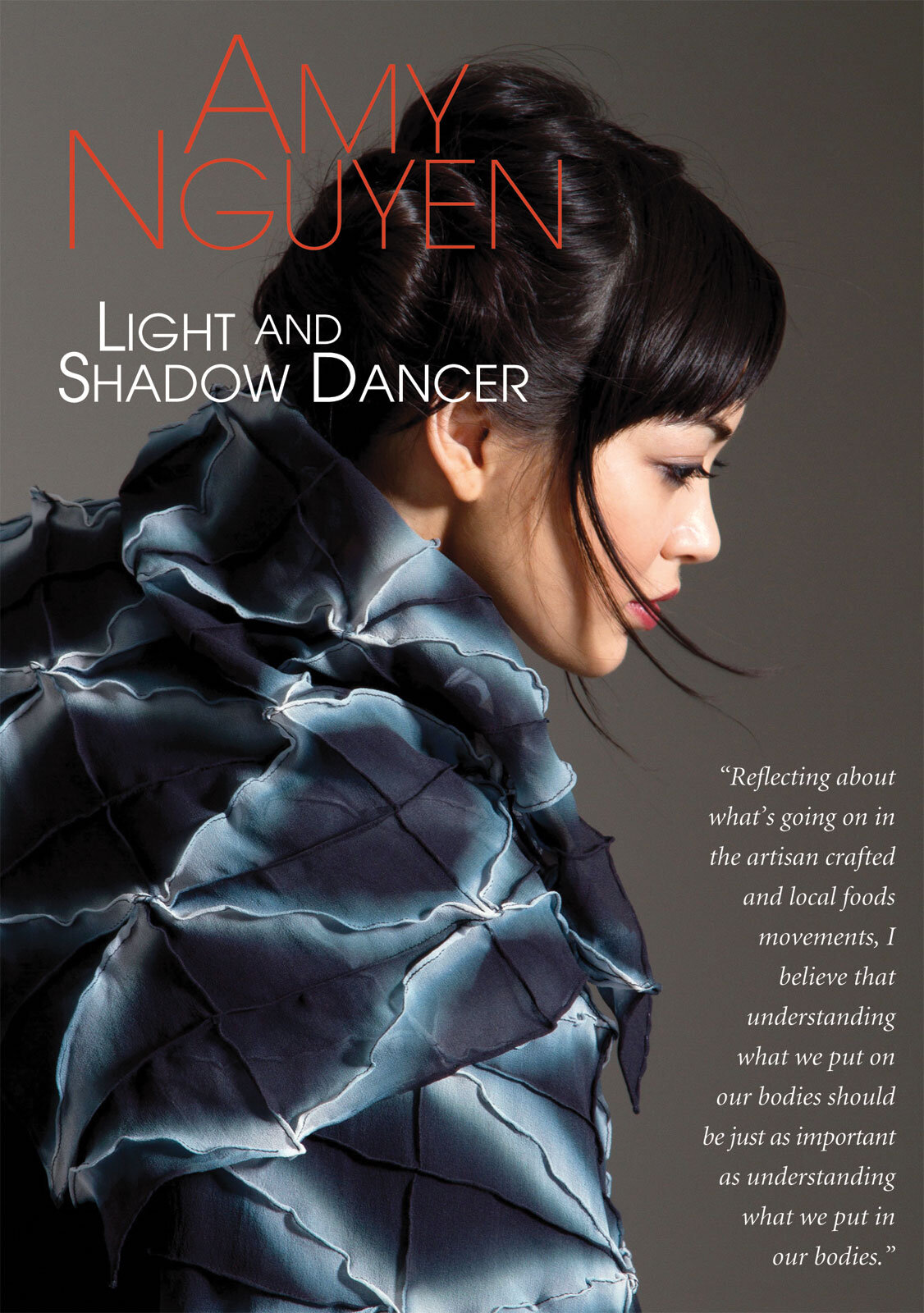

Amy Nguyen

3D SIGNATURE SCARF of silk chiffon; hand-dyed itajime shibori, formed, stitched, 2011. Photographs by Bob Packert.

Amy Nguyen’s path in life seems to be like the surface of a lake mirroring the sky above, a reflection of her ever-evolving aesthetic expression. That expression seems rooted in the balance between light and dark, finding the thin line of harmonious juxtaposition of two opposing elements. Finding and treading that middle ground, whether through the artistic or in her daily routines, is the most salient aspect of Nguyen’s character.

In several sacred traditions, it is the trinity or a duality which is the emanation of the divine. Whether Hinduism’s triune of the Creator, Preserver and Destroyer, or Daoism’s Yin and Yang, East Asian epistemologies in particular point to the necessity of balancing various essential forces, rather than the Western Judeo-Christian ethos of a monopolar spirituality, a world of opposites in conflict.

This is the thread that ties itself throughout Nguyen’s work and into the way she approaches her life. Never settling into a single mode of being, always incorporating that which seems opposed into a harmonic whole, a clear lesson to be learned from Nguyen is that we can reconcile the seemingly contradictory aspects of our world, to great and transformative effect. Whether it is working her Buddhist meditation and yoga into her long days working at the studio, getting a strenuous physical workout from her shibori dyeing, or flirting with the interplay between black and white in her flowing coats and vests, one can easily trace the trend of putting seeming opposites together into one.

Nguyen’s creative journey follows that organic process many artists can relate to. Her mother, a teacher and a quilter, was Nguyen’s first introduction to textiles. Nguyen’s recollection evocatively conveys her mother’s propensity for organization. “As a child, I remember admiring the colored spools of thread arranged by my mother for quilting and sewing. The spools were arranged by color and I could stare at those colors for hours—the silk-covered cotton threads I continue to use today.” One can imagine threads of crimson, dark greens, bright yellows, and subtle burgundies hanging off a spool board. Due to this early influence, Nguyen has been sewing “for as far back as I can remember.” The progression was straightforward: stuffed animals, pillows and quilts, then on to her own clothing. “I poured over fashion magazines looking for inspiration. I sketched designs. I remember staying up late to finish sewing outfits for special occasions at school—mostly dresses and accessories.”

The procession from teddy bears to dresses proceeded eventually to profession. Nguyen received a degree in studio art from the College of Charleston, South Carolina, with a minor in art history and theater, where she would be employed as the college’s costume shop supervisor. After that, she began freelancing, supported by additional income from music and art store jobs. Her freelancing work in sewing and fashion design brought her into contact with Mary Edna Fraser. Fraser, an adept batik artist, saw some of Nguyen’s paintings and suggested transferring them to fabric. “I am ever so grateful for her encouragement,” Nguyen remarks. “So I began to dabble in silk painting—I had access to supplies at the art store where I worked—gutta and liquid dyes. I fell in love. I began to explore other dyeing techniques and when I moved to New York City shortly after, I continued my dyeing on cloth.”

SHIBORI DYEING PROCESS showing linen fabrics after an over-dye, in its final rinse.

ASYMMETRICAL VEST of paper-like silk organza; hand-dyed itajime, deconstructed, pieced, stitched, 2011.

AMY NGUYEN.

Nguyen’s artistic path divides and entwines like a helix. At each stage, the past reverberates with the present, and a new development adds to the whole. From her mother to sewing, from Fraser to cloth dyeing, and then on to the New York University’s Department of Design for Stage and Film, Chair Susan Hilferty and Japanese fashion. Hilferty often wore Issey Miyake’s sculptural dresses, and these structural, gravity-defying pieces were a delight to Nguyen. Working there also introduced Nguyen to another famous Japanese clothing artist, Itchiku Kubota (see Ornament Vol. 32, No. 1). Because of her interest in Japanese fashion, and having access to the formidable costume archives of Hilferty, Nguyen found a book on kimono artist Kubota.

Kubota’s transcendent waterfalls of color and hue captured the young artist’s imagination, and particularly aimed her towards shibori. Kubota, whose stunning kimonos perhaps represent the apex of Japanese color expression through textiles, was the first step towards a new direction in Nguyen’s artistic career. Drawn into the research of shibori, Nguyen spent several years experimenting with the dyeing technique on her own. Eventually, she learned of Yoshiko Wada, the president of the World Shibori Network, who was offering classes at the Penland School of Crafts. Taking Wada’s course in 2004 opened up a new world for the artist, as Wada’s focus on concepts taught Nguyen to think in new ways. “She pushed you to think about what this ‘force and resist’ really can be. For example, I remember a story she told about trees in Japan which are wrapped and when unwrapped the growth of the bark is a type of shibori. Footsteps embedded in fresh sand is a type of shibori,” Nguyen explains enthusiastically. Wada succeeded through these examples in expressing the elemental simplicity of shibori, positive and negative. During this time Nguyen also studied with Joy Boutrup. Where Wada taught Nguyen to perceive in new ways, Boutrup laid down foundational knowledge. Nguyen has an incisive nature in examining herself and her life, able to clearly identify pivotal points. In her list of mentors and influences, she sums up each one as carefully as if their contribution to her life elevated her to a new plateau of understanding. “Yoshiko Wada introduced me to thinking outside of the box in terms of textiles. Joy Boutrup instilled in me the need for safety when working with dyes. Jason Pollen’s best advice was to carve out a small bit of time each day to experiment with no outcome in mind. This has helped me to see failures as part of the process—a big help in the process of creating.” One can see each person’s lesson as being extremely salient in Nguyen’s mind. Like seeing a video of a piece of origami being made in reverse, each fold of the paper could represent a gem of wisdom imparted by Nguyen’s mentors.

And how does all this culminate? The answer is in an ever-evolving aesthetic blended from increasing complexity that is eventually resolved into sublime simplicity. It is this careful collection of threads that converges to create well-informed, finely crafted and diversely influenced majesties of silk, light and shadow. Nguyen’s most recent work is highly coherent; the theme she plays with is flawlessly incorporated across all her numerous garments. One can see how her earlier work was a seamless prelude to her current series. Layering, quilting, the distinctive forms of circles and squares laid against contrasting backgrounds, these traits can be seen in subtly tweaked reiteration in her most recent work. The palette has shifted, with fewer colors in evidence, just a variegation between bright and dark. In her distinctive and mesmerizing layered coats, strips of dyed cloth are cut and restitched to create a shimmering wall of shibori. Using black or deep navy blue contrasting with white, subtly fading from one color to the other within one strip, and vibrating from one strip to the next, sometimes creating patches of dark or light, or alternating stripes, the end result is nearly a reverberation of sensation. “People wonder why I would rip and cut perfectly dyed cloth. It is this second layer that is so important to my work,” Nguyen explains. “It’s part of what differentiates my shibori. Deconstructing the cloth allows me to push further. It allows for beautiful dimension and an interplay between two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality.”

For her layered pieces, Nguyen sheds further light on their creation. “I first hand-dye itajime shibori on silk chiffon. The surface is then deconstructed by hand-cutting thin strips. I layer and piece these lines, deliberately designing the surface. I am creating a textured fabric from a single piece of flat silk chiffon. This cloth then is cut, edged, finished, and stitched to complete a garment.”

QUILTED COAT of paper-like silk organza; hand-dyed arashi shibori, deconstructed, pieced, quilted with fine denier microfiber, stitched, 2011.

Shibori has no direct translation in English, but is essentially a form of shaped-resist dyeing that has incredible depth due to many techniques. This means that the cloth is tied, crumpled or manipulated in any manner of ways, and then dyed and unfurled. The dye most heavily saturates the unshaped areas, while those parts of the cloth which were shaped are blocked from receiving the dye, forming patterns according to these reserved areas. There are many different shibori techniques, and itajime shibori is done by taking two pieces of wood and sandwiching folded and bundled cloth in between, which is then tightly bound with either cords or a vise, and dyed. The parts of the fabric not protected by the boards receive the dye; afterwards, the cloth bears patterns depending on how it was folded. In Nguyen’s work, this often forms square-like or circular patterns, although it is by no means limited to that. Graphic patterning and clean lines are the telltale. In contrast, arashi shibori produces stripes and wavy lines, testimony to the pole-wrapping technique where the cloth is wrapped diagonally on a pole, then scrunched to become a series of pleats. The pole is then submerged in the dye, and the areas between the pleats are reserved, forming the distinctive patterning.

The stitched method is her signature work. Itajime shibori is again used, either on silk chiffon, or paper-like silk organza. Piecing, folding and stitching are used to create the complete piece. “The stitching is such an important element as it adds weight to create the drape of the cloth I’m seeking. I have the control to create the size and shape of the piece I want to end up with.” This can be seen with the dimensional scarves Nguyen has made since before this current iteration of work. The stitch puckers the cloth, allowing it to drape while maintaining crimps that often reiterate the pattern of the dye. This process allows the scarf to possess a form of its own, standing daringly away from the wearer’s body.

The recursive theme illuminated in Nguyen is absorption and submersion. Her artistic process is tied into her Buddhist practice. The physical exertion of her dyeing is merely an outgrowth of her concern for her health and body. Synergy, mutual application, what Nguyen does is balance the artistic with the spiritual and the physical. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and provides stability in various walks of life. Her spiritual practice helps reduce the occasional nerve-wracking results of working as a craftsperson on the show circuit, and that peace of mind brings more easily the creative flow state.

“Buddhism was introduced to me by my father,” Nguyen explains. “He is a retired Presbyterian minister who went to Princeton Seminary and is a thinker and avid reader of all religions—a very open-minded man. He has introduced me to the ideas of Alan Watts, Thich Nhat Hanh, Pema Chödrön to name a few and to Zen Buddhism.” The idea of meditation was particularly intriguing to Nguyen. In the highly stimulated life of the modern American world, being able to calm oneself and find a place of stability and quiet from which to work on her art is invaluable. Nguyen’s work days can go for at least fourteen hours, and keeping limber through yoga, as well as recentering the mind help make the artistic process less physically stressful. Having grown up with Juvenile Type 1 Diabetes has made Nguyen mindful of her own health and body. “I notice that when I’m physically feeling my best, I’m able to create my strongest work. Similarly, I’ve learned not to work on a piece when I’m angry or upset—inevitably, something will go terribly wrong with the cloth. Instead, I go for a walk, or find another way to clear my mind. I believe the mind has to be still and at peace when creating.”

The shibori artist’s relationship to Asian aesthetics and concepts extends to family. Her husband Ky is Vietnamese, and he will often assist Nguyen at the craft shows, as well as in the studio. His family practices Buddhism, and as in most East Asian cultures the religion has deep roots. “There is great respect for ancestry,” Nguyen explains. “I think of how much I respect the age-old textile traditions and techniques and yet I create my work with a modern aesthetic. The roots are most important, though: blending the old and new.”

SHEER FIT CIRCLE COAT of paper-like silk organza; hand-dyed two-patterned shibori, formed, pieced, stitched, 2011.

Nguyen credits innumerable influences as having impacted both her life and her work. Japanese fashion designers certainly have their due, such as Yoshiki Hishinuma, Akihiko Izukura, Yohji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo, as well as Hilferty’s beloved Issey Miyake. Nguyen was very appreciative of Alexander McQueen’s exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Vionnet’s bias, Dior’s details, Yeohlee’s minimalism, Worth’s silk draping, Delaunay’s geometry—they all inspire me in different ways. It’s so hard to list only a few.”

Nguyen is not only an artist, but a fervent thinker who considers craft as a form of social activism. Matter-of-factly, it can be pointed out that not so long ago, all clothing was made by hand, often using local materials. “I feel a responsibility to continue and grow craft in my community. I feel it’s important to keep future generations making and collecting textiles,” she states. “Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, by Elizabeth Wayland Barber, gives us a sense of how important cloth is to society. Clothing made locally, with great care and the attention on the sourcing of materials, should be of utmost importance in our society. Made-by-hand items, requiring years of studying and refinement of craft, should be collected, treasured and pursued.” Nguyen’s goals for the future are as much craft activism as they are personal interests. Going back to her confluence of art and health, she expresses a desire to create textile installations for use in healing centers. “Tactile art reaches us in ways that can’t be described. I’d utilize my exploration with color and my understanding of how the human mind reacts to it. A recent exhibit by Motoi Yamamoto, Saltworks: Return to the Sea, featured at the Halsey Gallery at the College of Charleston, inspired me greatly. It helped me see a direction of my own current work in larger scale.

“These are some of my goals and visions. They change over time but these have been written for some time now on a list that is very important to me. There are personal goals on this list as well, and the reason they are all listed together is because I consider my textiles a part of my life, a part of who I am. What doesn’t change is the most important thread through all of this—creating a sustainable textile business through which I am educating, collaborating and eventually teaching, all while working in the studio on my own textile creations.

“Educating the public about textile crafts in the United States is a high level priority of mine,” Nguyen explains. “Reflecting about what’s going on in the artisan crafted and local foods movements, I believe that understanding what we put on our bodies should be just as important as understanding what we put in our bodies. For instance, where does the fabric come from and what is its content? Whose hands have worked on it? Who has dyed it and how do they work with dyes? Who has created the garment?” These basic questions are certainly not in most of our minds when purchasing clothes, even though they are perhaps present when buying organic produce.

“I really believe small artists, like myself, are invaluable not only to the future of textiles, but to the future of community in this country. I am beginning to see more and more that the ‘slow textile’ movement is imperative to our society’s survival. Fast is not always better. By endeavoring to handmake what we produce as local small business owners, we are able to positively impact our communities in sincere and personal ways. People connect with one another in a more meaningful way, are more present with each other, and inevitably this leads to a deeper sense of respect and appreciation.” Each artisan, thus embedded in the local community, takes root and grows vital, acting just as plants do to prevent erosion. For what is implicitly expressed in Nguyen’s call is the obvious; buying local keeps money in America. But that pragmatic reason is only part of the larger picture, one in which Nguyen is working to find her place within, as a contributing member to and creator of beauty for a healthier, humane and more balanced economy.

Click for Captions

Related Reading

The Creative Miracle

Marketplace For the Future

Patrick R. Benesh-Liu is now Coeditor of Ornament and grew up in the office on La Cienaga Street in Los Angeles. A mixed use property with the Benesh-Liu family house in front and a two story office building separated by a small lawn served as the young boy’s proverbial daycare. An old spiral staircase separated his mother’s groundfloor office from the upper level, where the rest of the staff worked. He would return again to work for the magazine during high school and shortly after returning home from college. Benesh-Liu accompanied Carolyn on many of her craft show voyages, and through the time spent with his parents has developed a deep understanding of contemporary craft. He contributed this article on contemporary shibori artist Amy Nguyen back in 2012, when he was still an Assistant Editor.