Aaron Macsai & Frances Kite 44.2

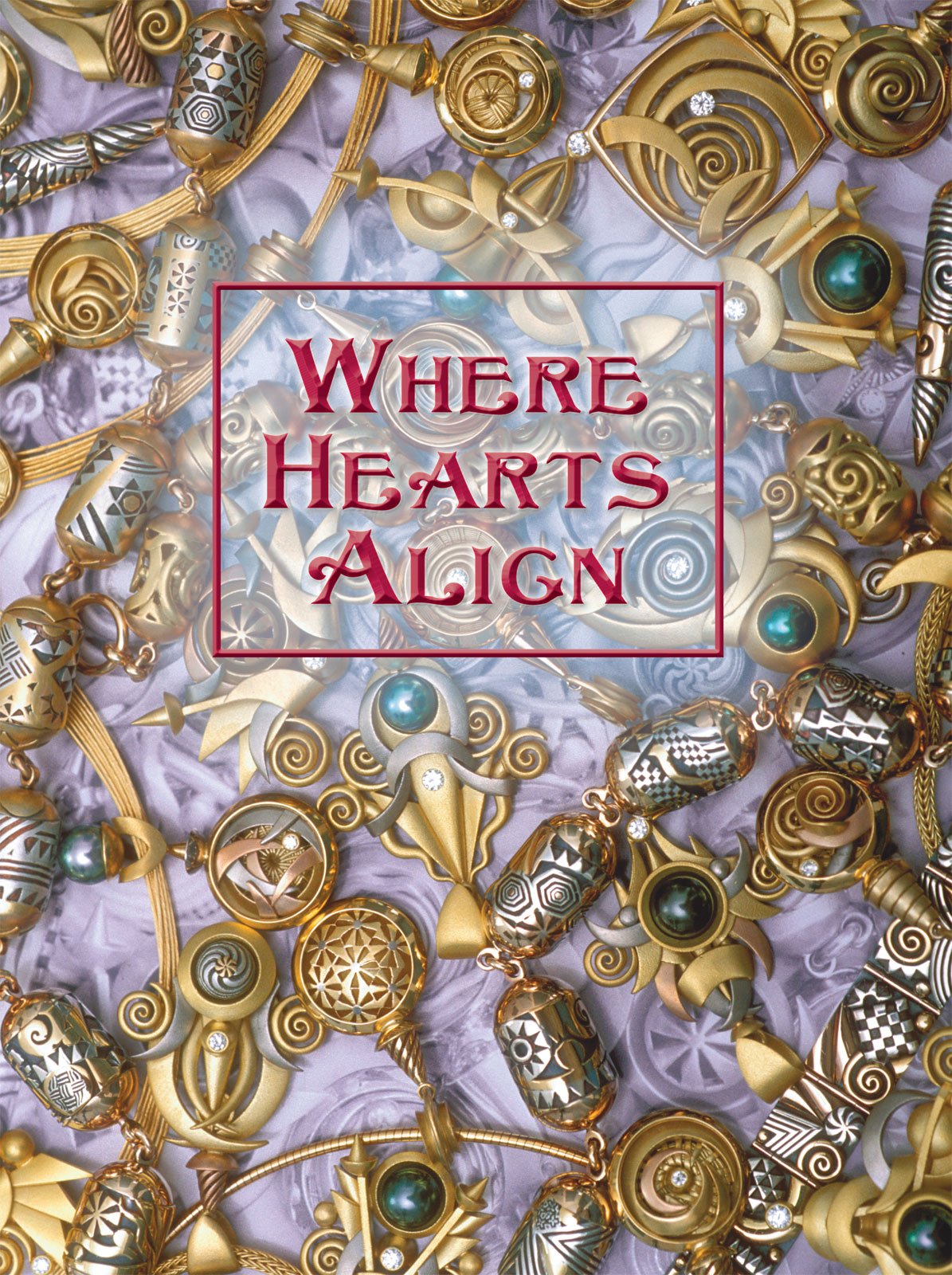

PHOTOGRAPHY COLLAGE by Aaron Macsai, 2008. Macsai photographed the pieces of jewelry, printed the image in black and white, placed the pieces on top of the photograph, and photographed them again. Photographs by Aaron Macsai.

AARON & FRANCES in Aaron’s corner of their shared studio, 2023.

Some days, everything goes wrong. Early one morning in 2011, Aaron Macsai set out from Chicago with a van full of display cases and his exquisitely crafted gold jewelry for the Paradise City Arts Festival in Massachusetts. He decided to take the route through Canada, so he crossed the border in Detroit. Much to his surprise and dismay, the Canadian border agent would not let him enter the country without either leaving much of his work at the border uninsured or paying a $20,000 bond. After half a day of answering questions and having his van searched, Macsai, frustrated, turned around and headed back over the bridge to the United States, planning to drive south of Lake Eerie instead. However, the presence of two fancy pocketknives (a gift for a fellow artist) on his dashboard caused the U.S. border agent to ask him if he had any other weapons and to please pull over to the side. After a few more hours of delay, Macsai, worn out and distraught, called the organizer of the craft show and said that he would not be able to make it. She persuaded him to try again, though, and by late that evening he was sitting forlornly in his assigned area with a pile of unpacked boxes.

Some days, everything goes right. Frances Kite made it to the same arts festival on time and was ready to share and sell her colorful cloisonné jewelry. It was an unfamiliar venue, and after wandering off for a snack, she took a wrong turn while heading back to her booth and ran into her long-time craft fair friend Aaron Macsai. Over the previous three decades they had developed a great respect for each other’s work and enjoyed visiting together every few months or couple of years in different parts of the country as their paths crossed at craft events. They were married people, and it was all very proper. This time they began with the customary pleasantries, and Macsai asked Kite about her husband, to which she replied, “Well, we’re divorced.” He asked her to repeat that. Kite recalls, “[He] got this big smile on [his] face, and… said, ‘I am, too,’ and I swear, I felt the universe shift.” She was flustered. Macsai adds, “It took us all night to set up; she was no help. We just talked and talked and talked….We were like high school kids with a total crush.” Kite picks up the story, “You brought me coffee in the morning and java chip ice cream in the afternoon and asked me to dinner.” They went to dinner together each evening, then returned to their homes, Kite to Kansas and Macsai to Illinois, after the show. Pretty soon, though, they started dating, and she moved to Chicago. Macsai sums it up: “We’re the two luckiest people in the world.”

HEARTS & FIRE of cloisonné enamel collaborative pendant, 18 & 24 karat gold, fine silver, .12 ct diamond; individually fabricated components, soldered, then sandblasted, with a final fiberglass brushing, 2.5 x 2.5 X 0.6 centimeters, 2019.

Frances Kite grew up in a small town in rural Nebraska on a wooded hillside, the youngest of three children. She enjoyed collecting interesting stones in her driveway and learning to look at nature with her mother. On the rare days when she was home sick from school, her mother would get out a jewelry box and share stories about the ancestors who used to own each piece. “I would get to know my family through the jewelry.” Kite went to college at the University of Kansas, where she studied jewelrymaking. One of the requirements was an enameling class, which got off to a rough start. “The first few days we worked with copper, and we were sprinkling on enamel, and I thought, ugh, this is so messy, I hate this.” But, when the teacher introduced cloisonné, she realized that she could do enamel and keep everything “perfectly neat and tidy.” With this ancient process, small wires or strips—often of gold—are attached to the base and used as little walls to divide the enamel into discrete compartments. Kite was hooked; this was in 1977, and she has been working with cloisonné ever since.

Aaron Macsai grew up in Chicago with three sisters. As a child, he loved going on sunrise walks with his father, to find shells when they visited Florida or fossils in strip mine piles near Lake Michigan. They went to museums—Aaron was mesmerized by the miniature worlds of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Thorne Rooms and fascinated by the cylinder seals at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute (now the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures). His father, John Macsai, was a volunteer archeologist and took Aaron with him on a summer dig in Israel when he was thirteen, as a Bar Mitzvah gift. By profession, though, John was an architect, contributing several modernist towers to the lakefront, so they also toured many Frank Lloyd Wright houses, looked through design books and observed buildings together. John taught architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Aaron recalls that “he didn’t stand for any mistakes, craftsmanship was important to him,” and adds, “part of me was always trying to please him.” John Macsai also was a Holocaust survivor—he was from Hungary and was liberated from Mauthausen concentration camp at the end of the war. Though John did not talk about this part of his life while his children were growing up, Aaron was always aware of it.

Aaron Macsai attended Southern Illinois University at Carbondale in the mid-1970s where he studied with Brent Kington, whose passion was blacksmithing. Kington taught him metalsmithing techniques appropriate to blacksmithing and told him that if he wanted to make jewelry, he should use found materials. Though an undergraduate, Macsai was skilled enough for Kington to allow him a graduate studio space, and he enjoyed the camaraderie of the older students. After college, Macsai spent a year apprenticing with a goldsmith in Chicago, where he learned to make gold jewelry. He then began his career as an independent artist.

Click to Enlarge

PANELS OF MOVEMENT of various colors of 18 karat gold, 14 karat yellow gold, sterling silver, 19.1 x 2.5 x 0.6 centimeters, 1996. This pattern metal bracelet illustrates the meticulous process Aaron follows. He creates cross-section slices of extruded patterns using silver, gold and copper. He solders these elements to the silver rectangular blanks. He then solders on various 18 karat gold elements that he has fabricated, trimming any excess metal. He solders on 14 karat gold tubing for the hinges. Then he paints everything except for the patterns with asphaltum, so that the copper is etched deeply to accentuate the design. Finally, he oxidizes the entire piece and polishes the highlights.

FIRESTARTER of cloisonné enamel collaborative pendant, 18 & 24 karat gold, fine silver (cloisonné panel), .15 ct & .06 ct diamond, 4.4 x 3.0 x 0.6 centimeters, 2019.

MONET ECHOS of 14, 18, & 20 karat gold, boulder opal, .15 ct diamond, 6.4 x 3.2 x 0.6 centimeters, 2004.

When Macsai first saw Kite’s work at the 57th Street Art Fair in Chicago in the early 1980s, he liked her fluid design aesthetic and how she blended organic and geometric elements. He also appreciated how giving she was with her knowledge. Curious about enamels, he had called many leading enamel artists for information, but none would give him straight answers about their supply sources and techniques. He notes that Kite, however, “spent hours on the phone with me telling me exactly where to get what I needed—when I had a problem, how to fix it, and guided me without any hesitation—total sharing.” He moved on from cloisonné within a year, but emerged with “a whole new level of respect for Frances.”

TOP HAT GOLDEN FIGURE pin/pendant of various alloys and colors of gold, 14, 18, 20, 22, and 24 karat gold, diamond, 8.3 x 3.8 x 1.3 centimeters, 2004. The arms and legs rotate and flex forward and backward.

Kite approaches her designs with inspiration from nature and a positive outlook. She often seeks to convey the peaceful movements of air or water and to provide a sense of upward motion in her compositions. She and Macsai raise Monarch butterflies in their garden, and the moment of greatest beauty for her is in the few hours before the pupa hatches, when it starts to become transparent, and the golden wings become visible. This observation, akin almost to living enamel, is the magic she desires to celebrate through her work.

When Kite first saw Macsai’s jewelry, she admired his sense of design, his compositions, the variety of what he was making, and the fact that every element was handmade—nothing was cast or stamped. “I thought it was the most interesting jewelry out there that I was seeing at the art fairs.” His early work was heavily inspired by Art Deco designs. Guided by his architectural experiences with his father, he believed in the concept that if you are going to make an object, it should have elegance in its design. Macsai explains that Art Deco is technically difficult to fabricate in jewelry, with its mix of hard-edge lines and graceful curves, but he finds the style balanced, sleek and beautiful. Eventually, though, he grew exhausted with the demanding symmetry and the high polish he used to prefer, and began including softer, more fluid elements and matte surfaces for an appealing contrast. His jewelry is full of robust spirals, grids, cones, curving zig zags, undulating tendrils, dynamic movement, and occasionally a glittering round diamond. He alloys his own gold and has a reputation as a master technical engineer of small-scale metal. “I think in metal. I create little worlds that are precious. Whatever you see in my booth, I made from scratch.”

Macsai calls one technique that is unique to his practice “pattern metal.” Using a power rolling mill, a collection of vintage draw plates (pierced rectangular steel plates through which you pull wire to make it into smaller diameters or different profiles), and copper, silver, and gold, he creates rods that contain patterns in their cross sections (like millefiori glass canes). He began by soldering together square silver and copper wires and slicing the resulting rod to make a checkerboard flag for a racecar-themed commission, and his pattern metal has become ever more intricate over the last twenty years.

Now often using bits of scrap metal from other projects, he solders, extrudes, twists, and resolders the patterns multiple times. He has accumulated quite a collection of pattern metal that he uses in his jewelry in a variety of ways. Most recently he has included pattern metal elements (and details developed through his experiments with the manipulation of pattern metal) in his delicate gold and gemstone bead necklaces.

Though Kite and Macsai focus on different techniques and came to their ideas about craft and design by different routes, they have much in common as jewelry artists. They both believe that jewelry should be wearable, and that craftsmanship is paramount. They value precision, elegance and harmony. Kite, thinking about time spent talking with her mother about family heirlooms, says, “I want my pieces to be passed on through generations, too.” And Macsai realized recently that his desire to create precious objects that will outlive him is fueled in part by the museum objects he marveled at as a kid. These sympathies in artistic outlook now allow them to work together on jewelry. In Sea of Dance, Kite loves how the lines move seamlessly back and forth between her enamel and his goldwork. “We are both meticulous with our craftsmanship. I didn’t want [the lines] to be kind of close, I wanted [them] to really meet up.” In this work and Hearts & Fire, Kite used gold foil that Macsai made for her, cutting it with miniature tools he made for her; conventional gold foil falls apart like tissue, but his slightly thicker material allows her to introduce a whole new design element to her enamel. Their collaborations are not without moments of contention, but they both find the experiences rewarding. When asked what Kite’s work adds to his, Macsai states simply, “She gives it new life.” And Kite marvels, “It’s just incredible what we can come up with together.” She explains, “We put our love of life, our love of our experiences, our love of our talent into our work and we fill it with good energy and a positive approach to life.” Macsai adds with impassioned sincerity, “and we both believe it stays with the piece.”

RUNNING RAPIDS of various colors of 18 karat gold, 14 karat yellow gold, sterling silver, 19.1 x 1.9 x 0.6 centimeters, 1998. This is another pattern metal bracelet, utilizing the same techniques found in Panels of Movement.

“Though Kite and Macsai focus on different techniques and came to their ideas about craft and design by different routes, they have much in common as jewelry artists. They both believe that jewelry should be wearable, and that craftsmanship is paramount. They value precision, elegance and harmony. Kite, thinking about time spent talking with her mother about family heirlooms, says, ‘I want my pieces to be passed on through generations, too.’ ”

DREAMCATCHER NECKLACE of 18 karat yellow & green gold, .10 ct diamond, 5.1 x 1.9 x 0.6 centimeters, 2019. The six center linear elements are fused together and coiled to establish the focus, all other elements are fabricated separately and soldered together.

In 2015, with his father’s health deteriorating, Macsai and Kite quickly planned a wedding. They put together bits of gold from multiple generations of each of their families, and Macsai made rings with a simple triangle pattern around them. (He notes that they are nothing like what he eventually wants to make them and describes how pleased he is with the much more intricate rings he made for his son and son-in-law’s wedding.) Macsai adds that his dad “just loved Frances,” and looking at a photograph of his dad’s smile from that happy day brings tears to his eyes. He muses, “We’re entering a time in life, where we both know we have less rather than more years to explore new techniques, new work, new avenues, and it’s wonderful to have a partner that really gets it, that’s lived the life you live.”

During their careers, they both have received notable recognitions. In particular Kite was thrilled when curator Kenneth Trapp purchased a work of hers, Traveling on the Edge Brooch (which she made in memory of her mother), for the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, and Macsai is honored to have his Remember to Love panel (made in late 2001 as part of a 9/11 memorial) in the Museum of Arts and Design. But, they were especially touched to receive the 2023 Smithsonian Craft Show Excellence in Jewelry Award (selected by Patrick R. Benesh-Liu and Robert K. Liu in memory of Carolyn L.E. Benesh) as a couple, together. Attending craft shows is their preferred venue for selling work because of the personal interactions and the opportunities to talk about how their work is made, and they love being in a single booth: “We share with people in a genuine way, and we get back in return the fuel we need as artists to move on and create more pieces.”

SUGGESTED READING

Higher Education Channel and the Saint Louis Art Fair, “Meet the Artist: Aaron Macsai” video, June 30, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KHW_Xx_xTAI.

Le Van, Marthe, curator, Hemachandra, Ray, ed. Masters. Gold: Major Works by Leading Artists. New York: Lark Books, 2009.

Searle, Karen. “Aaron Macsai: An Exquisite Vocabulary,” Ornament Magazine: Vol. 16, No. 2, Winter 1992.

Click For Captions

PATTERN METAL CYLINDER BEAD NECKLACE of 18 & 14 karat gold, silver and copper; each bead is approximately 2.5 x 1.3-1.9 centimeters, 2023. These individual beads are cross-section slices of patterns Aaron fabricates in silver & copper, or gold & copper, and soldered together with 18 karat gold onto a silver backing sheet.

Ashley Callahan is an independent scholar and curator in Athens, Georgia, with a specialty in modern and contemporary American decorative arts. She has an undergraduate degree from Sewanee and a master’s degree in the history of American decorative arts from the Smithsonian and Parsons. Her publications include Frankie Welch’s Americana: Fashion, Scarves, and Politics (UGA Press, 2022), Southern Tufts: The Regional Origins and National Craze for Chenille Fashion (UGA Press, 2015), and, as co-author, Crafting History: Textiles, Metals, and Ceramics at the University of Georgia (Georgia Museum of Art, 2018). She enjoys every opportunity to learn about, talk about, wear, and write about contemporary jewelry. In this issue she shares the story of Frances Kite and Aaron Macsai, accomplished jewelry artists and soulmates.