Shuoyuan Bai Volume 43.1

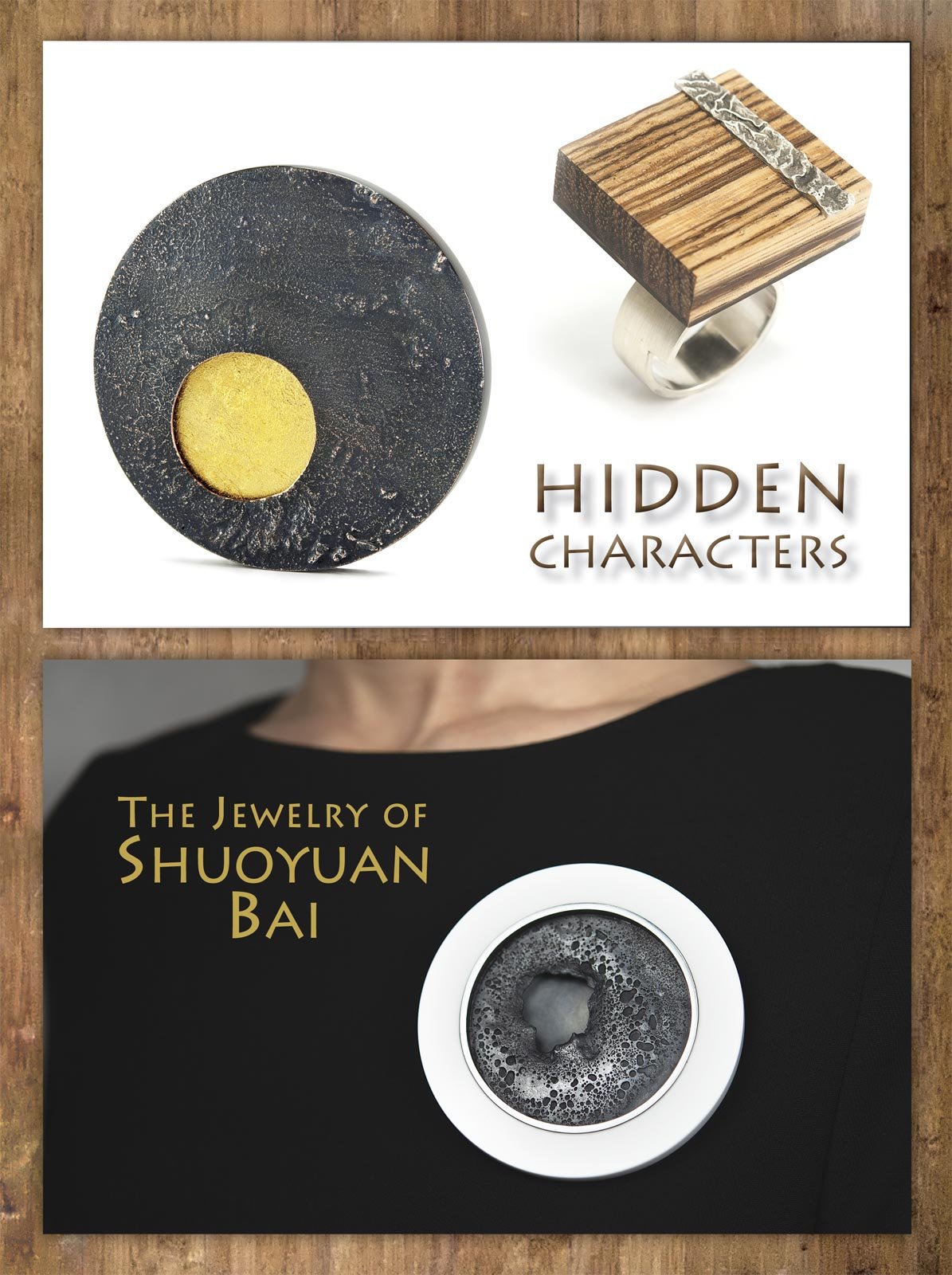

UNTITLED NO. 2 BROOCH of copper, sterling silver, carved acrylic, 23.5 karat gold leaf, stainless steel (pin), 7.0 x 7.0 x 1.3 centimeters, 2018.

RING NO. 4 of zebrawood, reticulated silver, shibuichi, sterling silver, 3.0 x 3.0 x 3.5 centimeters, 2014.

SUNKEN BROOCH of acrylic, copper, sterling silver, stainless steel (pin), 8.0 x 8.0 x 1.0 centimeters, 2019. Photographs by Shuoyuan Bai except where noted.

It’s the dark side of the moon that gets revealed in Shuoyuan Bai’s jewelry. It is erosion and the volcanic earth, of small and bright against large and dark. He plays with contrasts and materials, exhilarating in texture. Like miniature picture frames in a future perfect 1950s style house of crisp plastic and chrome, his brooch surrounds pitted black metal with a flawless white rim. It reminds one of the meteorite jewelry created by Kirk Lang; cold, dark space iron is easy imagery to invoke in the mind’s eye.

OVAL RING of rhodolite garnet, laser etched acrylic, sterling silver, 6.7 x 4.1 x 1.2 centimeters, 2016.

SQUARE BROOCH of laser etched acrylic, 23.5 karat gold leaf, sterling silver, stainless steel (pin), 6.0 x 6.0 x 1.3 centimeters, 2016.

BRIDGE RING of acrylic, 23.5 karat gold leaf, sterling silver, reticulated silver, 6.0 x 5.5 x 1.2 centimeters, 2016.

SHUOYUAN BAI. Photograph by Xun Liu.

That’s just a starting point for the visual voyage Bai brings you on. His A View in Frame series, which includes the stark Sunken Brooch, incorporates acrylic in different roles. Whether used as a frame in the former, or as part of the background, a dimpled white fingerlength bisecting two rust-like, oxidized plates, as is the case for Oval Ring, acrylic performs the accompanying act for the other materials. Untitled No. 2 Brooch conjures a first unusual example of acrylic use. Brushed with gold leaf, a golden disk appears inset, nestled near the rim. In Square Brooch, acrylic’s abilities as the protagonist are tested. Light suddenly becomes an integral element, reflecting off of and illuminating the golden interior of laser etchings.

In Bridge Ring, shadow is now a participant. Carved branches of brilliant gold leaf acrylic cast an inky blackness on a plain white backdrop. It may remind you of Chinese scholar rocks; perhaps arms of coral, or of the light cast through the windows of the Forbidden City. Environment and architecture are big influences for Bai, who is from Shenzhen, China. His parents were encouraging and open-minded, and from an early age he knew he was interested in the arts. Extracurricular activities are part and parcel of student life in China, and Bai was provided with a drawing teacher each weekend. For primary school education, Bai had the opportunity to study in the United States, and his artistic interests found fertile ground there. His high school introduction to craft started in Bethel, Maine, where he took silversmithing in high school, in a tiny cottage that held the tools and torches. It was a big transition, from being a Southern Chinese city boy to the wilds of Maine, and Bai was taken from a hot, southern environment to his first introduction to snow. After graduating, an encounter at a Boston college fair led him to a booth, chaired by a metalsmith adorned with silver rings, from the Pratt Institute. The young Bai was blown away by the jewelrymaker’s handiwork, and the fact that he had made them himself. After several years in New York and finding his urban roots again, his high school mentorship led him to SCAD at its Savannah campus. His Maine silversmithing teacher had gone for a school visit at SCAD right around the time the college was revamping its jewelry department, and had been impressed by the inventory of tools and workspaces available to them. But at the time, the call of New York was too alluring. It was only after the formative period at Pratt that Bai was ready to pursue the new experience at SCAD.

Each residence contributed fertile ground for growth. At Pratt, the jewelry department was right below the furniture-making department, and so for his bachelor’s thesis, Bai used leftover wood that had been discarded for his brooches and rings. In this series, The Grain, he was drawn to the flaws and irregularities in the wood. So often these pieces were the detritus of the furniture department, since they compromised structural integrity, yet as a simple block for a brooch or bracelet, suddenly the complexity of the wood’s scar became a rich visual element. Bai pairs these focal points with raw semiprecious stones, like aquamarine and amethyst, prong-set and at most gently etched. The wildness of the stone and wood’s surface harks back to the unshaped primordial form of the scholar’s rock, and a connection is shared. In this small corner, where imperfections are beheld, life begins its dance.

Bai lives for the creative journey inherent in following the process. Until things get physical and he’s actually touching tools and material, the work is all theoretical. “There’s only so much you can do with your imagination, but then for us, especially we who work with our hands extensively, a lot of our thinking actually happens on our fingertips,” he laughs. He recalls his own path towards becoming an artist, and thinking with one’s fingertips is a concept that holds great attraction for him.

“I was very interested in how things work. That ultimately led me to working with my own hands. Because a lot of the big jobs, the more practical jobs, are very computer based, very office based, and I never felt that was part of me. And art, as a very general term, I think for me is about doing what you enjoy, but also find meaning within it. Like at the end of it, you want to find some sense of fulfillment. It doesn’t matter where that part comes from. You want to feel like you’ve spent your time creating something worthwhile.”

This deep reverence for the handmade belies Bai’s very inquisitive perspective. He seeks to create a modern Chinese aesthetic that fits in the contemporary sphere, and this quest leads him to question and seek new applications for the materials he is working with. “Traditional techniques used in traditional jewelry form, they are very fully developed. How can I say it... they’re kind of limiting, because you have to take a traditional material and using modern technology to combine it to make something new. But if you’re using a traditional technique, and traditional material, it’s hard to get out of that limitation. So I think it’s a mixture of something that’s from the past and something that is new. So for me I look at the aesthetic part of other things, other than jewelry, and specifically architecture. And trying to translate that into materials. I think I took the traditional aesthetic, using modern materials, and tried to work with that.”

Click for Captions

This careful appraisal and management of tradition, of expressing itself quietly without loud dynamics, leads to a certain sublimity in Bai’s work. The rawness and experimental nature of The Grain, with its inquiries into the material of wood, play upon a similar focus on a point of contrast as Bai’s A View in Frame. In the latter, a quiet potentiality, provided by the metal, is the backdrop to a small exception, a slight dissonance in the piece’s order. These visual exceptions, whether it’s a splash of gold on oxidized silver and copper, right along the crease of a junction, or a tear giving the viewer a glimpse into the interior, draw the observer in until their curiosity is satisfied.

His reflections on contemporary art jewelry in China are realistic. Bai sees interesting work emerging and more momentum in the Chinese contemporary jewelry scene, but it is only now beginning to pierce the public consciousness. It has taken a while for the teaching of contemporary jewelrymaking to become embedded in Chinese education, and as there are more Chinese students learning in the United States and more traveling abroad, that wave is building.

As a pilgrim finishing his journey back at the beginning, Bai has recently returned to New York City. Here to find new prospects and reconnect with the busy, fast-paced life of the big city, Bai is eager to see what his fingertips dream up next.

You can see more of Shuoyuan’s work at www.shuoyuanbai.com.

Patrick Benesh-Liu is Coeditor of Ornament and a lifelong participant in his parents’ creative journey. From growing up in the Ornament office on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles to his first administrative work in the Vista, California building during high school, Benesh-Liu has had the fortune of being immersed in craft, culture and wearable art. Now as one of the two guiding editors for the magazine, he continues to reflect on the vital work his mother and father have done in advancing the historical chronicling of jewelry and clothing artists for over forty-eight years. He contributes to this issue an examination of the work of Shuoyuan Bai, a Chinese contemporary jewelry artist whose artistic education from high school onwards was in the United States. An MFA graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design, Bai was introduced to Benesh-Liu by Jay Song, the Chair of the jewelry department at SCAD while at the Smithsonian Craft Show. Benesh-Liu was immediately taken by the quiet beauty and excellent craftsmanship of Bai’s jewelry. After a recent book was published on contemporary Chinese jewelry, he decided to interview Bai, whose work is a promising addition to the art jewelry scene. He also pens a new department called Destinations, reporting on contemporary wearable art galleries around the country.