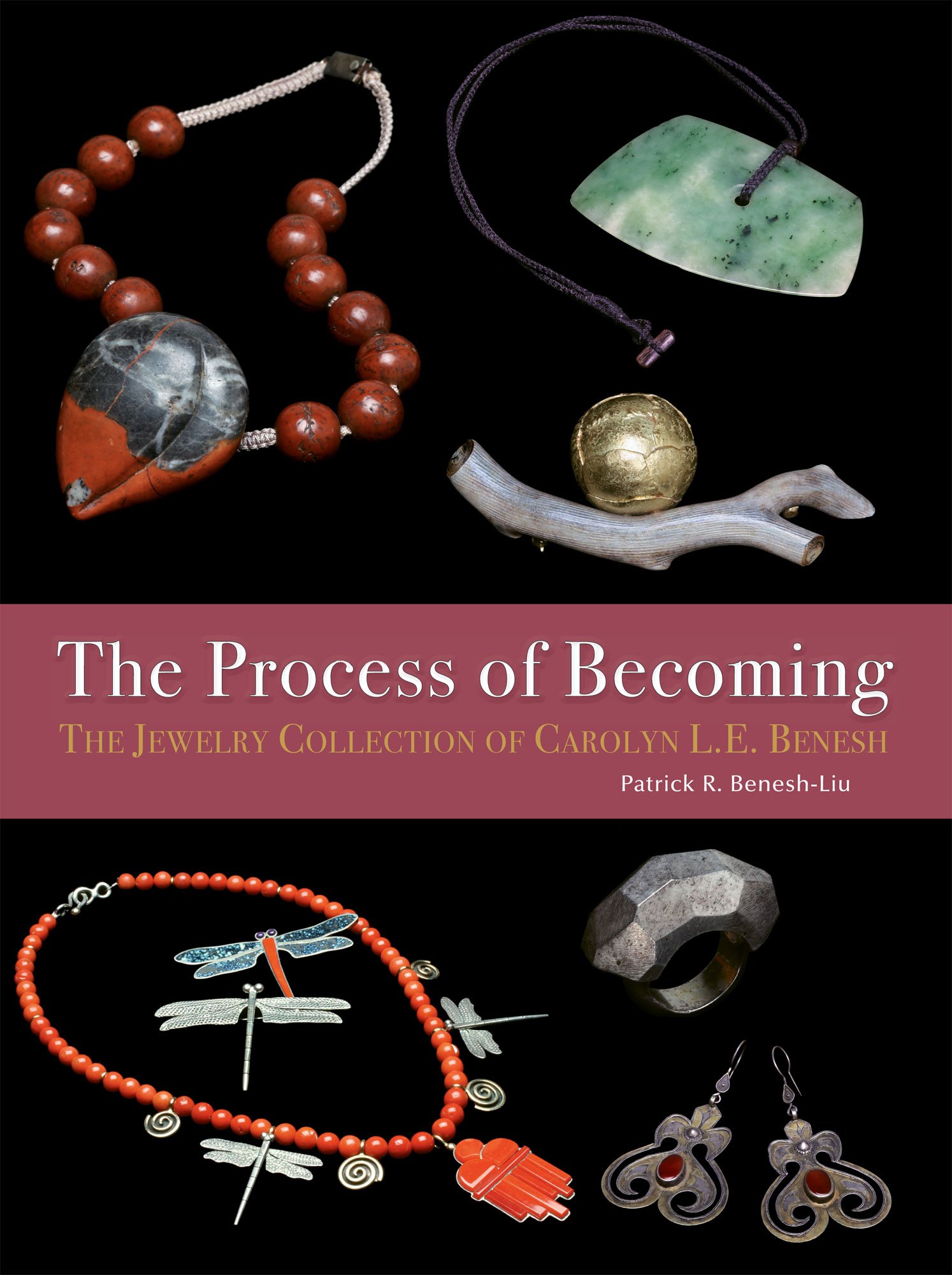

The Process of Becoming 42.4

Clockwise: NECKLACE by Fumiko Ukai of seed beads, agate peach pendant, 4.3 x 1.0 centimeters. CARVED PENDANT by Steven Myhre of green jade, hand-braided cord, goat horn clasp, 3.5 x 0.3 centimeters. BROOCH by Ken Loeber & Dona Look of eighteen karat gold, fossilized coral; fabricated, 3.0 x 1.3 centimeters. RING by SB (artist unknown, initials are carved on the ring) of silver; fabricated, faceted, 1.5 X 1.0 centimeters. This was a favorite ring. PAKISTANI EARRINGS of silver, carnelian; gilded. Photographs by Patrick R. Benesh-Liu except where noted. CLOUD NECKLACE by Christina Anna Eustace (Cochiti-Zuni Pueblo) of coral, sterling silver, fourteen karat gold; 4.3 x 0.3 centimeters. DRAGONFLY BROOCHES of sterling silver, or coral, sugilite, turquoise; 2.5 x 0.3 centimeters. Photograph by Robert K. Liu/Ornament.

CAROLYN L.E. BENESH while interviewing jeweler Genevieve Yang at her mother’s home in Northern California in 2016; here you can see her wearing a brooch by Reiko Ishiyama. Photograph by Robert K. Liu/Ornament.

It’s hard to sum up the immense personality, grit and spirit of the late Ornament Coeditor, Carolyn Louise Eva Benesh. Many people remember her for her warm smile, which seemed to radiate and embrace those in her presence like the sun’s rays warm the earth, or for her laughter, which would ring out across a crowded craft show hall. Yet to reduce her to just these traits would be a mistake. She was stubborn, smart, resilient, incisive, brave, curious, explorative, joyful, and wise. Seeing only the surface dismisses the deep reserves of strength and complexity that roiled below, with layers upon layers of insight and contemplation that had been hard won through a life fully lived.

If you spoke to those who became friends with Carolyn they would likely have given different reasons as to why they were drawn to her. A beneficence of spirit would be a common one; the way she made you feel is another. In truth, what she did was make space for you to be who you actually were, and she made room for the misfits, the shy and introverted, those who had seemingly tough skin but who in reality were big softies underneath. She listened; that was the key component in her magic. At a craft show, where artists have to stand for hours, often times with no one present, she was there to stand with them, to fill the silence with laughter, and to pay attention, to receive the worries and anxieties that we all have, to listen gravely and with due concern. One was part of something larger in her presence, a shared humanity that was connective and hopeful.

My mother was an optimist, with an unshakable faith in humankind’s ability to learn and grow. What was so remarkable about this faith was that it wasn’t grounded in wishful thinking. Carolyn was clear-eyed about the world and the fullness of its flawed nature, but this same clarity of vision gave her access to a perspective cynics often find obscured, and that is the grace and generosity that people are also capable of. She saw this in people of all stripes, and she made new friends easily, whether that was a taxi driver, a hotel porter or a waitress at a sit-in diner. Or, as the case may have been, a jewelry artist.

Whenever Carolyn purchased a piece of jewelry from somebody, it was never just a transaction; it was a reciprocal exchange of respect and recognition. Sometimes only a few words were imparted, at other times, a whole conversation preceded the final purchase. This happened whether the maker she was acquiring the newest piece in her collection from was an old acquaintance or someone she had just met. It didn’t matter. The same understanding that led her to found the Bead Journal with my father, Robert K. Liu, grounded her in each interaction, which was this; that a handmade object was expressed through a human hand, and a human heart. She treated both the object and the person who made it as if they were one and the same.

YEMENI PRAYER SCROLL PENDANT of silver on chain; fabricated, granulated, appliqué. ENAMEL BROOCH by Barbara Minor of fabricated silver, enamel on copper, dry screen printed enamel, twenty-four karat gold leaf on black enamel, 2007. Carolyn eyed a similar piece by Minor at the ACC Baltimore show one year, and asked Barbara to make one in black and red. EARRINGS by Heinz Brummel of fabricated, oxidized silver, resin, onyx, gold earwire; accompanied in box by artist design sketch, 1993.

A bit of background is in order, as the surface is never so sweet as the tumultuous layers. Ornament Magazine began as the Bead Journal in Los Angeles, and after a few years my parents purchased a duplex on La Cienega Boulevard, with financial help from her mother and father, Kathryn and Peter Benesh. Peter had created his own company, Benesh Incorporated, from the ground up, thanks to his education at the Henry Ford Trade School as an adolescent, and it delighted both he and Kathryn that their daughter had taken up the mantle of entrepreneurship. For both my parents, they were an indispensable source of support.

That duplex on La Cienega became more than just home and workplace. During those heady first years, it would host an array of guests from around the world; bead traders, ethnographic dealers, artists, family, and more. The parties that were held there brought a vivacious cross-section of people who were involved in beads, jewelry and wearable art. It was at this nexus that Carolyn’s collection began to take shape.

Many of these visitors stayed in the guest bedroom; sometimes, they would live there for weeks or even months. Some made jewelry in Ornament’s workshop, a part of the duplex that was outside of my little world of the house and the office. The community that Robert and Carolyn warmly embraced were an extended family of humanity.

EARRINGS inscribed with the initials DC of silver, enamel and copper, 1992. CARVED WOOD BROOCH by unknown artist of tropical wood. This elegant teardrop shape made from a single material is an example of Carolyn’s appreciation for beautiful simplicity.

This helps explain how my mother interacted with the artists she met and befriended throughout the years. After we moved away from the roar of Los Angeles to a sleepy San Diego suburb named San Marcos (scouted, again, by Kathryn and Peter, who didn’t want their grandson growing up in the air pollution that was still endemic to LA at the time), opportunities to meet the people she was so fond of changed and shifted. Travel to shows, whether it was the Indian Market in Santa Fe, or the Philadelphia Museum of Art Craft Show and Smithsonian Craft Show in Washington, D.C., became the venue for connection.

One of my favorite childhood destinations was the Southwestern states of Arizona and New Mexico, as they always heralded a visit to a Native American exhibition or fair. Indian Market in Santa Fe was an education; the narrow streets filling up with booths stretching in every direction was just so much busyness for a young mind. Later on we would visit the Heard Indian Fair and Market in Phoenix, and in both places, Carolyn was in her element. She spoke with many artists, and while their contact was limited to this once-a-year visit, somehow it seemed like they’d known each other forever. She was particularly close with the Lovato family, a sprawling collection of grandmother, father and sons who all made jewelry. She purchased several tufa-cast bracelets and rings from Anthony Lovato himself, who always had a quick wit and broad smile to match her own.

Anthony’s mother, Mary Coriz Lovato, was another artist who made her way into the Carolyn fan club. Her mosaic inlay hand brooches are iconic, with little details like coral fingernails and a metal wire spiral set in the wrist. These simple elements transformed a base representation into a spiritual symbol. Carolyn had a great appreciation for the hand; I often remember her commenting on how beautiful someone’s hands were, including mine. This reflected an intimate understanding of what the human hand was capable of, not only in the making of jewelry, but as the manipulator of the pen and the keyboard, the tools of her craft.

BRACELET by Anthony Lovato (Santo Domingo Pueblo) of silver and rutilated quartz; tufa-cast, 2.5 x 2.5 centimeters, 2004. This and another ring by Anthony were frequent appearances on my mother’s wrist and finger. CROSS PENDANT of sterling silver, mother of pearl, turquoise, tufa cast; 2.0 x 0.5 centimeters. PENDANT by Mary Coriz Lovato (Santo Domingo Pueblo) of cow bone, turquoise, coral, spiny oyster, onyx, 2.0 x 1.5 centimeters. HAND BROOCH of silver, mosaic onyx or jet and coral; 2.5 x 0.5 centimeters. SPIDERWEB CUFF by Joel Pajarito (Santo Domingo Pueblo) of silver, turquoise; tufa-cast, 2016. Another favorite of my mother’s. DRAGONFLY BROOCH by Aldrich Arts (Caucasian) of sterling silver, sugilite, turquoise, and opal, 2.75 x 0.5 centimeters, 1994.

One of Carolyn’s favorite stories was that of Bartleby the Scrivener by Herman Melville. A copyist who is hired by an elderly lawyer, Bartleby eventually stops doing any work at all, replying calmly to each entreaty with the words “I would prefer not to.” My mother took her own interpretation away from this short piece of fiction (another illustration of how art so often escapes the intentions of its maker). In Bartleby, she saw a strange revolutionary, a misbegotten soul who refused to be a cog in the machine. This passive stance of rebellion struck such a chord with her that she took the pencil as her personal talisman. A fitting development in her life of transformation, since she had formerly wielded the brush as an aspiring painter in art school.

Stories like these, which are the building blocks of the self, are often the seeds for the objects we find ourselves drawn to. That’s true for any possession, whether it’s a bit of kitsch that we might buy in a pawn shop, or a ring passed down to us by our mother. The difference with a piece of jewelry is that it is worn, and thus more than any object aside from clothing is a part of us. In indigenous and tribal cultures, the adornment that people wear is their public identity. But we have more layers than an onion, and sometimes that which is publicly worn has a private, secret life that only the wearer knows.

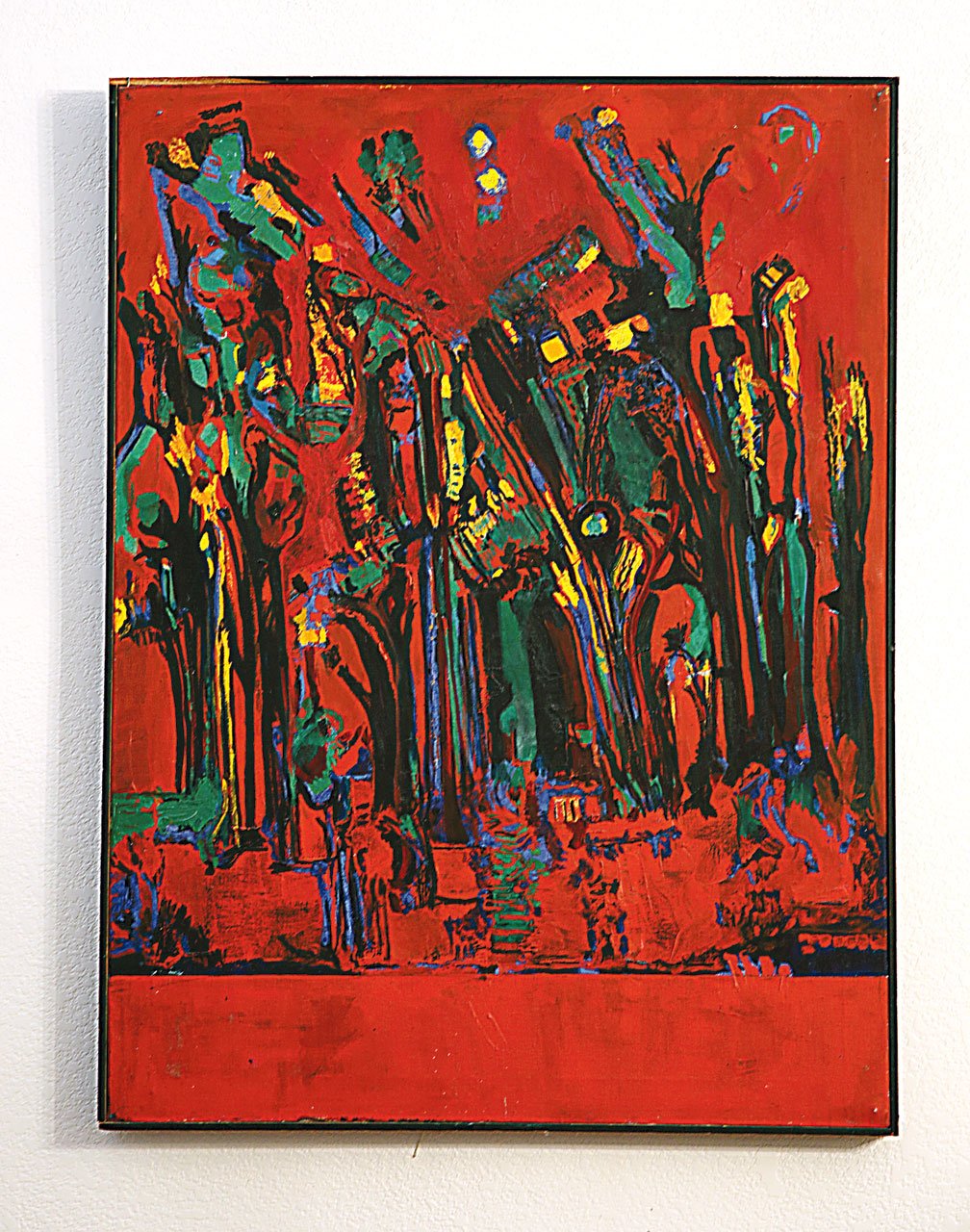

CAROLYN AT LA POSADA HOTEL in Winslow, Arizona, during a 2017 trip to the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe. This strange and wonderful inn was a favorite stop of hers. SILVERPOINT pendant by Roberta and David Williamson of sterling silver; fabricated, cast. UNTITLED PAINTING done by Carolyn L.E. Benesh during the 1960s when she was a student at the Art Department of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Photograph by Robert K. Liu/Ornament.

BEAST BROOCH by unknown artist of sterling silver; fabricated, engraved, patinated, 1991.

Well-made jewelry reveals the secret heart of our imagination, and as one meanders through Carolyn’s jewelry collection the sheer depth and breadth of that realm is laid bare. My mother never discriminated as to the source for her jewelry, apart from the requirements of authenticity, quality, ingenuity, and a sense of humor. So antique Native American cuffs and pins commingle with pieces purchased from extant artists at the Heard Indian Fair & Market; Middle Eastern jewelry from Yemen and Afghanistan, likely bought at an ethnographic dealer, thrives alongside magnificent East Indian bangles and necklaces procured during her culinary tour in India. There are dozens of works from contemporary jewelry artists, most of whom have been featured in Ornament. But simply relating the dazzling variety misses the point. It’s not about numbers, it’s about the thoughtfulness imbued into each and every piece she owned. She never purchased something unless it added something unique to her collection.

Jewelry is a language that differs from all others, even that of other wearable art such as clothing. This is because it can be small, and regardless of size, is always of an intimate nature. The comparison is often made of jewelry being miniature sculpture, and for some artists this analogy is embraced and appropriate. However sculpture does not belong to someone; it stands on its own, while jewelry is always incomplete without a wearer. From ancient times to the present day it is a method of communicating, a dialogue between the person who has pinned that brooch to their lapel, and the curious onlooker who strolls up and says, “What is that?”

LITTLE FRIEND RING by Roberta and David Williamson of vintage monkey print, sterling silver; fabricated.

There is no doubt that this implicit necessity of interaction was a reason behind Carolyn choosing to cover jewelry in Ornament. In the work she purchased one could also see a canny gaze that selected pieces that were provocative. An unknown bronzed brooch, stark and wild, encases a perched bird on a branch within a nest of words: Desire. Want. Need. Outside of this protective barrier paces a feline, thick, bushy whiskers and an irritable countenance speaking to deep, predatory instincts denied. No precious materials exist here beyond the repoussed and etched metal, yet the primal emotions at play beat out like a heart out of control. There is an air of dark humor that plays about this piece, and while at first glance we derive bubbling mirth, a prolonged contemplation finds one teetering on the abyss.

My mother loved cats, and she herself was a Leo, a fact she justifiably was proud of. While not putting much stock into astrology, she did comment from time to time on how fittingly a zodiac sign matched a friend, and when her fellow Leos had a birthday bash there was cause for much rejoicing and celebration. Monkeys also figured prominently into her collection, with the majority coming from the poignant artistry of Roberta and David Williamson. Carolyn’s Chinese zodiac sign was that of the monkey, the trickster, and between her two birth signs she found all the representation she could ask for.

BROOCHES by Kim Kelzer & Marcia Macdonald of painted wood, sterling silver, silver granules; fabricated.

The Williamsons represented part of another select group, whose friendships existed in the luminous space of the craft show circuit. She would see these artists perhaps once, at most twice, a year, on her annual voyages to Washington D.C. and Pennsylvania for the Smithsonian and Philadelphia Museum of Art Craft Shows. It may seem silly to say that deep bonds can be forged under such circumstances, but participating in the repetitive rhythm of life can create strong connections. Of course many had known her for years and years before the shows; the first article on Roberta and David was in Ornament in 1984. But it was there, in the great cavern of the National Building Museum and the halls of the Pennsylvania Convention Center that joyous reunions took place yearly.

These contemporary jewelers find their apex under the tension of having to sell their work to the public. Friends like Ken Loeber and Dona Look produce breathtaking distillations of the natural world. Loeber experienced a stroke in the early 2000s which paralyzed half his body, and so Look, who is an accomplished basketmaker herself, began to assist in making the production jewelry, the bread and butter of sales. Now, examine one of Ken’s one-of-a-kind brooches. A branch of fossilized coral possesses a melancholy grace. While it resembles the outstretched limb of a tree, somehow its ancient underwater origins suffuse the senses. A golden orb sits atop this venerable bough, bringing to mind all manner of associations. Is it the sun, shining softly through? Perhaps it is a bird, perched and preening. Could it be a nest of some kind, harboring the young of a new generation? The mind’s eye plays through the possibilities.

Another bosom buddy of my mother is Judith Kinghorn, whose jewelry is similarly inspired by the boundless beauty of nature. The two of them could always be found at a craft show on Preview Night, off giggling away at a quiet table, or conversing at Judith’s booth, enjoying the back and forth exchange of memories and ideas. Kinghorn’s approach is more representational than Loeber’s quiet abstraction, boisterous and jubilant in its depiction of flora. Her secret garden expresses the essential nature of her specimens, rather than seeking a literal translation of their being. Somehow, it seems more real that way. The Lichen brooch my mother purchased is simple, yet it evokes the heady pleasure of the deep forest.

The net of friendship was cast far and wide for Carolyn, with another hub of connection being through Freehand Gallery in Los Angeles. Its owner, and now also the Executive Director of Craft in America, Carol Sauvion, was her partner-in-crime. Both woman had a baby boy around the same time; Noah Reitman and I grew up together for the first few years of our lives, spending our childhood years playing at the Sauvion household. One of the artists who sold at Freehand, Steven Myhre from New Zealand, found in Carolyn and Robert fertile ground for community. His work encompasses the carving of bone, shell and stone.

LIFE SERIES NECKLACE by Myung Urso of sewn silk, sterling silver, 2007.

Myhre hails from that strange lineage of the self-taught artist, although he also spent time learning from native Tongans that helped cement the authenticity of his craft. His carved pendants are beloved by the whole Benesh-Liu family for their grace and eloquence, and Carolyn was a prolific purchaser. In those heady early days, Myhre spent three weeks in our workshop, carving bone and putting up in the guest bedroom. His wife, Mary-Anne Crompton, worked for the New Zealand foreign service, and was a close confidant of my mother’s. Due to her diplomatic privileges they traveled often, and were a welcome visitor to the Ornament offices. There was always a ritual involved in these visits, where Myhre took the felt blanket containing his latest creations and unfurled it slowly, revealing jade earrings, spiral cow bone pendants, and the luminescent glow of New Zealand nephrite.

This slow and steady drumbeat of connection nurtured our lives. When viewing the jewelry Carolyn collected, one realizes that each piece represented a precious milestone of shared experience, and an appreciation for the intricate perspectives held by that artist. Myhre’s sublime carvings hold a grave respect for the traditions of the Maori people, and those of other Polynesians, for their connection to the spiritual and to Mother Earth. The polymer jewelry by Steven Ford and David Forlano, reviewed by Ornament way back in the day when they were still called Citizen Cane, are part of a great experiment these two artists began in collaboration and teamwork. Polymer clay was a novel medium in the 1990s, and Ford and Forlano went a step further in the creative endeavor by taking a leap of faith with each other. When Carolyn purchased that pin, which incorporated additional materials in the form of silver, she was acknowledging the worth of their newest exploratory mission.

PAPER BROOCH/PENDANT by Nel Linssen of folded paper, elastic (allowing expansion), 1991. MAP BROOCH by unknown artist of sterling silver, copper, pearls, map of the former Yugoslavia (undoubtedly a reason for her purchasing it, due to her Serbo-Croatian heritage); fabricated, stamped, oxidized. BRACELET by Coen Mulder of forged anodized aluminum, pre-2000s. HYDRO TOP PIN by Steven Ford and David Forlano of multi-color polymer, sterling silver; fabricated, die-formed, roller-printed, 2002. BROOCH by Biba Schutz of fabricated copper, woven silver wire, silver granules. LICHEN PIN by Judith Kinghorn of oxidized sterling silver and gold; fabricated, 2009.

Not all of my mother’s collection came from artists she met face to face. Her extensive collection of ethnographic and antique jewelry reflected her appreciation for astute craftsmanship, wherever and whomever it came from. She particularly loved jewelry from India and China, the former because of the rich lineage of personal adornment that touches every corner of society, the latter for similar reasons, but also a feeling of kinship with the people from her husband’s homeland (notwithstanding the fact he himself was born in Rome!).

Focusing on her as a collector obscures what was most amazing about my Mom. For forty-six years, she published a magazine that recorded the stories of hundreds of artists, and educated people about wearable art traditions from around the world. She knew that jewelry and clothing coverage was underrepresented in the field, and that many of these incredible craftspeople would have gone unnoticed except for a few footnotes in a research paper or book. Carolyn fundamentally understood that jewelry and clothing were the most personal of artforms because they are inextricably intertwined with our bodies and identities.

She also realized that there’s a practical, pragmatic side to the arts, and that despite the romanticization of the starving artist, there is no real glory to be had if the path of the arts requires a vow of poverty. While she supported craft professionally through her documenting the lives and stories of artists, there was also the financial aspect. This wasn’t some form of charity, either; it was an implicit recognition of the vital importance of exchange. By giving and receiving, we ebb and flow, making movement. Life is about movement, and growth. With each piece of jewelry she collected, Carolyn paid tribute to this essential truth.

INDIAN BRACELET of silver; fabricated, with exceptional chainwork, probably purchased when she was on a culinary tour of India. ART SAVES LIVES PIN by Maria C. Moya of resin, paint, imitation crystal; 2.0 x 0.3 centimeters, 1988. ELEPHANT CUFF by Bhagwan Das Soni, from Jaisalmer, India of silver; formed, repoussed, chased. Bought at a Fowler Museum trunk show in 2017 by Patrick R. Benesh-Liu as a gift for his mother. MIAO SILVER FISH TORQUE from China; fabricated, forged, engraved, wire-work, purchased from her friends Paddy Kan and Anne Lee at Leekan Designs in New York. DO IT: DON’T DO IT PIN by F. Dagg of ceramic. SEEDS & POLLEN SERIES NECKLACE by Kathleen Dustin of pierced 3d printed resin or nylon beads; 8.0 x 0.8 centimeters.

You Might Also Like

A Luxurious Metamorphosis

Patrick R. Benesh-Liu is now Coeditor of Ornament and a lifelong participant in his parents’ creative journey. From growing up in the Ornament office on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles to his first administrative work in the Vista, California building during high school, Benesh-Liu has had the fortune of being immersed in craft, culture and wearable art. Now as one of the two guiding editors for the magazine, he continues to reflect on the vital work his mother and father have done in advancing the historical chronicling of jewelry and clothing artists for over forty-eight years. In this special edition he contributes a review of the Craft in America Jewelry episode, where both he and Robert K. Liu were interviewed amongst several jewelry artists, all of whom have been covered in the magazine. He also writes about his mother’s extraordinary collection of jewelry, which was the subject of an exhibition at the Wayne Art Center in Wayne, Pennsylvania.