Bead Dictionary Letter C

Introduction

In the late 1990s, Penny Diamanti, Joyce Diamanti and Robert K. Liu started working on a Bead Dictionary. Around 2009, after much work by the Diamantis, the Bead Dictionary was posted on the Beadazzled website. Through the years, additions were made by Beadazzled. In the summer of 2018, when the Washington DC Beadazzled store and its website closed, the Bead Dictionary was offered to Ornament. This is a unique resource, especially rich for information on beads of ethnographic and ancient origins. As Ornament has only a staff of three, we are slowly reposting it on our website, updating or expanding some of the entries and are adding search features, links and references as time permits. The Bead Dictionary covers primarily beads and other perforated ornaments, but also tools and materials used by those who make jewelry utilizing beads. Photographs from the Ornament archives are being added, as well as new images taken expressly for the Bead Dictionary and others are being brought up to current standards, as many of these images are almost 30 years old. Original photography was by Robert K. Liu, while Cas Webber did additional photos for Beadazzled, noted in the captions as RKL or CW, after first captions.

This Dictionary of Beads is a labor of love and a work in progress. We welcome your comments and suggestions through the Contact link. To navigate, select from the visual index above to jump to the letter you want in the Dictionary, but give the page a little time to load first. To get back to the top and select another letter use the arrow button. We are continuously adding to the Dictionary, so check back often.

To search for keywords in Dictionary headings, use your browser's search function; for example in Internet Explorer use Control+F and in Apple Command+F, then type in your keyword. We hope you enjoy this (not-so-tiny) treasure, and learn more about the vast world of Beads.

Cable Chain

Sterling silver drawn cable chain, characterized by elongated loops. Plain cable chain has round loops. CW

Cable chain is made up of links that are simple round loops. It is available with links of many different diameters. In addition, cable chain comes in both base and precious metal. Drawn cable chain has oval loops.

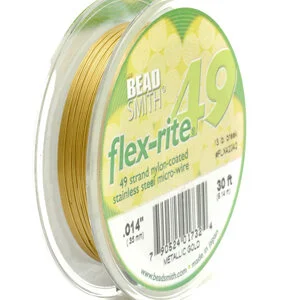

Cable Wire

Cable wire consists of strands of steel wire twined together and coated with nylon, which may be clear or colored. The number and thickness of the individual wire strands determines the diameter, flexibility, and strength of the cable wire. This wire works well for bead stringing because it is strong and resists stretching and fraying The higher the number of strands the less prone to kinking the wire is. Jewelry strung on cable wire should always be finished with crimps.

Cable wire is made by a number of different manufacturers. The more prominent brand names of cable wire include the following:

Beadalon® beading wire comes in 7-, 19-, and 49-strand versions. Flex-Rite® uses state-of-the-art micro-wire technology to produce a cable that is strong, soft, and flexible in a versatile range of colors, materials, diameters, and strand counts. Soft Flex® beading wire comes in diameters of .014 inch (fine), .019 inch (medium), and .024 inch (heavy). Soft Flex cable wire is available in many colors and including a variety of metallics. Soft Touch® beading wire is 50% softer and more flexible than the original Soft Flex wire. It is considered a premium cable wire and comes in four diameters: .010 inch (very fine), .014 inch (fine), .019 inch (medium), and .024 inch (heavy).

Miniature steel cable is an extremely strong yet flexible beading cord. CW

Soft Flex brand cable wire Extreme edition. CW

Flex-rite brand cable wire. CW

Calipers

Brass calipers, with upper measurements in inches, lower in millimeters. CW

Calipers are useful tools to measure the size of items, usually in metric or inches. Most useful are dial calipers in metal or plastic, where measurements are read on a dial, making it easier to read.

Cambay

Many, if not most, of the carnelian beads found round the world originated in Cambay, or Khambat, a stone-working center in Gujarat, in western India, where the exploitation of rich deposits of carnelian as well as onyx and agate dates back more than 6,000 years. As early as 2,500 BC Harappan bead cutters shaped Cambay carnelian into long elegant bicones that were traded to Mesopotamia.

From AD 1300 the lapidary industry flourished in the Cambay area, as craftsmen produced Muslim amulets and prayer strands, and great quantities of carnelian beads for the African market. Arab traders ferried these goods to eastern Africa in monsoon-driven dhows, or carried them to Mecca and Cairo and thence into western Africa via camel caravan.

The 19th century brought competition—first from carnelian beads and ornaments carved in Idar-Oberstein in Germany, then from molded glass imitations made in Bohemia—and the Cambay bead trade declined. But Africa remains the major consumer of the region’s output.

The high iron content of Cambay carnelian accounts for its rich red-orange color, which is brought out by drying the stones in the sun and repeatedly heating them in simple kilns. This process and other techniques and tools used by Indian artisans have changed little over thousands of years. Their beads are less uniform in size and shape, and are drilled with less precision than modern machine-made beads produced in Taiwan and Hong Kong. But the Cambay carnelian beads have the warmth and beauty that comes from being hand crafted. Because of their enduring appeal, Cambay is still one of the largest stone beadworking centers of the world.

See Also: Agate Carnelian Idar-Oberstein: Talhakimt

Carnelian beads from ancient Cambay, India, collected in Africa with some crystal and possibly indigenous granitic beads. RKL

Cameo

A design, often a human head in profile, carved into a layered stone or shell to reveal and make use of the different colored layers for contrast between the foreground and background of the image. The technique was popular in ancient Rome under Augustus and revived during the late Renaissance. Pressed glass cameos acheive a similar effect with far less effort.

See: Stamping

Cane

A long, thin drawn rod of glass used in lampworking for making and decorating beads. Canes are also bundled, fused and sliced to create mosaic cross sections that are applied to glass beads for mosaic or millefiori effects.

See Also: Lampworked Beads Millefiori Beads Venetian Trade Beads Mosaic Beads

Cane Beads

An obsolete name for drawn beads, which are also sometimes called blown beads or furnace glass. Unlike lampworked glass beads that only require a torch (or "lamp") to make and decorate them, drawn beads require a furnace where large quantities of glass can be melted before being drawn out into long tubes, which are then sliced or pinched into beads. Blowing is generally not part of the drawing process, except to insert a bubble of air into the "gather" of molten glass. As the gather is drawn into a tube that can be 100 feet or more long, the bubble is also elongated forming the hole in the center of the tube.

Closeup of Indo-Pacific beads, most likely made in India, using the lada method, and not with a blowpipe. In Africa, these are often called nila beads. Courtesy of the now closed Bead Museum, Washington DC. RKL

Canton

City in southern China (today known as Guangzhou) where beads were made since at least the 18th Century. The name Canton beads has sometimes been erroneously applied to any Chinese glass bead of the 18th or 19th Century.

See Also: Chinese Glass Beads

Capped Beads

Long Carnelian and silver bead from Nepal and capped faux Amber bead from Mali, West Africa. RKL

Sometimes gold caps are permanently applied to the ends of valuable ancient stone beads—such as etched carnelians, dZi, and related banded agates—to conceal damage or reinforce fragile beads. This style has been copied in some contemporary silver-capped beads from Nepal. The new beads most frequently capped in this way include carnelian, amber, turquoise, and some naturally banded agates or imitation dZi.

Capstan Beads

Capstan beads are spool shaped beads. Chinese examples, like those shown below, are actually ear plugs or ear decorations, although how they were worn is not known.

See: Ear Spools—Ancient Chinese Erhtang

Ancient Chinese glass erhtang, or ear spool, probably lapidary-worked; also known as a capstan bead or spool bead. This type dates from the Han Dynasty. See Liu (1991, Ornament 19/1). Courtesy of Dirk Ross. RKL

An assortment of Chinese glass erhtang—also called capstan, or ear spool—beads of the Han Dynasty, courtesy of Dirk Ross. These ear ornaments are also found in Japan and Korea. Earspools of the preceding Zhou Dynasty differ in size and shape. Courtesy of Dirk Ross. RKL

Carat

A unit of weight for precious stones. One carat is equal to 0.2 grams. The term should not be confused with karat, which is a measure of the purity of gold.

See Also: Karat

Carnelian

Various shapes of new Indian carnelian beads. RKL

Carnelian, also spelled cornelian in Britain—from cornaline, the French term for the stone, probably derived from the cornel cherry because of its color. Translucent- to opaque chalcedony with a waxy to vitreous luster and color gradations from creamy flesh tones through rusty orange to dark reddish brown. In the natural variety, from India, the color, caused by iron oxides, is distributed uniformly or in cloudy patches. The color-enhanced variety, which is Brazilian agate dyed in Germany, shows striations when held against the light.

Widely used since antiquity in jewelry and other decorative objects, this stone was particularly popular for seals because wax does not readily adhere to polished carnelian. In addition to India and Brazil, Uruguay and the US boast deposits of this popular stone. Ancient Egyptian warriors wore carnelian amulets to give them the courage and strength to prevail over their enemies. Others, however, have looked to carnelian to still hot blood, foster good feelings, and strengthen the reproductive organs.

See Also: Afghan Ancient Hardstone Beads Cambay Etched Carnelian Beads

An assortment of long bicone carnelian beads, made in Cambay. Only the one with the large perforation is ancient, the others are replicas made so collectors will not buy authentic looted beads. RKL

Vintage Indian carnelian beads carved in traditional shapes. RKL

Carnelian Beads From Africa

Assortment of carnelian beads from the African trade, most probably Indian made, some indigenous African production, and a few Venetian glass beads. Courtesy of Picard Collection. RKL

Assorted shapes and sizes of vintage carnelian beads from the African trade, all products of the Cambay stone industry. RKL

Cased Beads

Contemporary cased glass beads. Clear glass casing adds depth and luster to drawn glass beads. RKL

Due to the cost and difficulty of making red glass, solid red glass beads of any size made before the 20th century are rare. Red or orange overlays or casing over white or yellow cores or matrices was found to be a good substitute. One example shown here is Chinese, probably from early- to mid-20th century and can be as large as 1.8 cm in diameter. Much more common are the various types of Cornaline d’Aleppo beads (commonly called white hearts) made in Venice, using the same techniques but of older vintage, which also have white or yellow cores. Contemporary American glass beadmakers frequently use a clear glass overlay on their drawn beads to add depth and luster to the color. Some also use an inner layer of white glass below the color to enhance brightness.

See Also: White Heart Beads Cornaline d’Aleppo

Antique, cased Chinese glass bead. RKL

Contemporary cased beads with acid-etched matte finish, made by Elizabeth Carey. RKL

Cast Beads

An assortment of American made cast and plated base metal beads. CW

Beads made by the process of casting, where molten metal is poured into a mold of the desired shape. Beads can be individually cast as in the lost wax process where the mold must be broken to release the finished bead, or mass produced in two-part, resusable molds. Although some cast beads are made in sterling silver, most consist of base metal that is often plated. Well-made cast beads can be both attractive and durable although they tend to be heavier than forged or stamped beads. Their relatively low price point and wide variety of shapes, sizes and finishes make them attractive to designers.

Rhode Island has been a center for casting in the US. Until recently mass produced casting of beads was not found in developing bead-producing countires due to the cost of equipment and scale of the operation required. In India, Indonesia and Thialand forging in home workshops remains the norm, while in West Africa lost wax casting of brass remains the traditionl method. However, China has recently emerged as a large scale producer of good quality cast beads. Apparently high volume production methods for making hardware and toys has been adapted to beadmaking with satisfying and profitable results.

See Also: Base Metal

Cat’s Eye

Chrysoberyl or chalcedony that exhibit chatoyance, a linear sheen of light that seems to move over the bead’s surface. Also a name for glass beads of various colors that shimmer with the opalescent cat’s eye effect. The glass cat’s eye beads have also been called "fiber-optic" beads because they are created with by fusing quartz fibers that are also used for fiber-optic cables.

See Also: Chatoyance Tiger’s Eye

Cedar Seed Beads

Found strung into necklaces in the American desert southwest, these beads are actually juniper berries and are used in Native American cleansing ceremonies. They are also known as ghost beads because of their association with the Ghost Dance.

Celtic Ring Beads

Glass ring beads, or ringperlen, are found in the United Kingdom and on the Continent, especially in Celtic sites. These annular beads may date to the late La Tène period of the last two centuries BC. Of pleasing shapes, like well-shaped doughnuts, they are often translucent green to almost clear when trans-illuminated. They range from 1.6 to 2.1 cm in diameter. Their trailed decorations are often feathered, as on the one shown, and the glass is usually in good to excellent condition. See Liu (1995, Collectible Beads).

See Also: Annular Beads Ring Beads Ringperlen

Celtic Ring Beads or Ringperlen, found in the UK and continent and dating to the Late La Tene period of the last two centuries BCE. When transiluminated, they are translucent green, almost clear; 1.6 to 2.1 cm diameters. RKL

Ceramic Beads

Chinese (top), Greek (middle) and Peruvian ceramic beads. CW

This term encompasses several distinct types of beads: those made from clay or earthenware and those made of porcelain as well as faience. China has a long and illustrious history of porcelain-making so it’s not surprising that most of the world’s porcelain beads are Chinese. Perennially popular, they come in traditional blue and white and multicolored patterns as well as brighter contemporary palettes.

Peru also produces porcelain beads, but is more famous for its hand-painted clay beads made primarily in and around Cusco. Additional ceramic bead types include extremely small (2-3 x 10-12mm), ridged tubular clay beads from Mali in West Africa, and clay spindle whorls used as beads, from both Ecuador and West Africa, especially by the Dogon people.

Artisans in the United States, especially Howard Newcomb, have produced some of the most subtle and sophisticated ceramic beads for necklaces, while others have experimented with bright glazes or rolling tubular beads over textured surfaces to make impressions in the beads which are then emphasized with dyes.

See Also: Newcomb, Howard Peruvian Beads Faience Chinese Beads—Contemporary

Contemporary clay and porcelain beads. RKL

Ceylon

Japanese size 8 Pink Ceylon glass Delica seed beads. CW

A pearly luster, usually produced in pastel colors and applied as a surface finish to seed beads and molded glass beads made in the Czech Republic, Japan, Taiwan, and France. There is no connection to the island of Sri Lanka, formerly known as Ceylon.

See Also: Seed Beads

Chain

Silver cable chain. CW

A flexible series of connected metal links. In beaded jewelry design links are often interspersed with beads or beads are dangled from links of chain. Chain can also form an adjustable extender or closure at the back of a necklace allowing it to be worn at different lengths to match a variety of necklines, or neck sizes.

See: Ball Chain Bead Chain Cable Chain Curb Chain Drawn Cable Chain Figaro Chain Long-and-Short Chain Omega Chain Rolo Chain Snake Chain

Chain Beads

Alternate term for glass snake beads, that have a zig-zag profile and interlock like snake vertabrae. Many, but not all, were made by the Prosser method.

See Also: Snake Beads Prosser Beads

Chain Nose Pliers

Chain nose pliers used for bending wire, crimping, and more. CW

These jewelry tools feature smaller and finer jaws than similar hardware store versions. Available with smooth or serrated jaws, which have half-round tips, they serve many functions.

Smooth jaws are handy for opening and closing jump rings, straightening out loops made with round nose pliers, flattening crimps (although crimping pliers create a more streamlined and secure finish), and many other uses. Smooth jaws have the advantage that they don’t leave marks on your work.

Personal preferences, budget, environmental conditions, and the type and amount of work you do will determine which pliers are best for you. Carbon steel is strongest, but will rust if not protected from moisture. Drop-forged and box-jointed tools stand up to more stress than die-cast and lap-jointed versions. Ergonomic handles and spring-action joints can reduce strain if you use your tools extensively. Size also matters. Tools with the same size jaws can have handles varying several inches in length. Choose the ones that fit your hands best. Mini tools find favor with children and beaders on the move.

Chalcedony

Translucent ancient chalcedony tabular beads. RKL

Chalcedony is the microcrystalline, or cryptocrystalline, form of the quartz group of gemstones. That is, it is made up of “microscopic,” or “hidden,” crystals, so small they are not visible to the naked eye, unlike macrocrystalline quartz, such as amethyst, which is composed of large crystals. Chalcedony occurs worldwide and has been prized since prehistoric times. It was probably named after Chalcedon, an ancient Greek port on the Bosporus, which may have been a transit point on a trade route that carried chalcedony to the Mediterranean region from sources to the east—Iran, Afghanistan, and India.

Today, these countries remain important suppliers of microcrystalline quartz as well as many other gem-grade minerals, both rough and finished. In Roman times, the area around Idar-Oberstein, in present-day Germany, provided raw agate and jasper to the classical world. In the 15th century a lapidary industry was established there to finish these materials. It grew and flourished until the mines were depleted in the 19th century. The major modern sources of chalcedony being exploited today lie in Brazil and Uruguay, who ship much of their output, mostly drab and colorless raw material, to Germany for processing in Idar-Oberstein, which has become a world-class lapidary center renowned for its sophisticated techniques for coloring, cutting, and polishing gemstones.

Chalcedony has many varieties, which can be divided into two types, those that are fine-grained and fibrous in structure and those that are granular. In addition to being the name of the species, chalcedony is the name of its purest variety, which ranges from a milky white to a beautiful pale lavender-blue in color. This “blue chalcedony,” as it is often called, is typically translucent with a waxy luster and displays no banding or other distinctive markings.

Other varieties owe their colors and patterns to mineral impurities. In addition, chalcedony tends to be porous, except for white layers, so most varieties can be, and often are, easily stained or otherwise treated to alter or enhance their natural coloration. Today methods that go back to antiquity as well as new techniques are widely used and are long-accepted practice in the gemstone world. Indeed, dZi beads, which have been revered in Asia for thousands of years and today are highly valued by collectors worldwide, are artificially altered agate.

The largest variety of chalcedony is agate, which has numerous subvarieties that are distinguished by parallel to concentric banding; they occur in a spectrum of many different colors, transparent to almost opaque. Onyx, though often misconstrued to be all black, has contrasting parallel layers of black or dark brown, alternating with white. Sardonyx exhibits similar layers of dark brownish red with white or cream. Iron oxides in carnelian create its range of hues from translucent pale yellowish orange to dark reddish brown. The apple green of chrysoprase is due to its nickel content; the leek green of prase comes from chlorite inclusions; and green agate gets its color from chromium. Moss agate contains mineral inclusions that form dark mossy flecks and fronds in a matrix of clear colorless chalcedony. Bloodstone gets its name from the splotches of red jasper spattered throughout its dark green core.

Jasper is also a microcrystalline quartz, and gemologists usually consider it a variety of chalcedony. But because jasper is granular, lacks distinctive patterning, and contains up to 20% foreign matter (making it the least pure form of chalcedony), jasper is sometimes classified as a separate species of quartz, which in turn has numerous varieties. They are generally opaque and, for the most part, red to ochre, but they also occur in shades of yellow and brown, green and gray blue. Some varieties are monochrome, some are striped (riband jasper) or have a circular eye-like pattern (orbicular jasper), and some display a crazy quilt of contrasting colors.

Chalcedony’s multitude of glorious colors and endlessly fascinating patterns attracted even our earliest ancestors. Agate found in France in association with Stone Age human remains provides evidence that the use of chalcedony for adornment goes back to the Paleolithic period. The mining of rich deposits of carnelian, onyx, agates, jasper, and other quartz minerals in the Narmada Valley in India dates back more than 6000 years. Around 2500 BC bead cutters of the Indus Civilization fashioned carnelian from this region into elegant long bicones, which they exported from Harappa (in present-day Pakistan) to the Royal House of Ur (in present-day Iraq).

The Egyptians have a long history of using many varieties of chalcedony before 3000 BC. Agate, carnelian, and chrysoprase were favorites for making beads and pendants to construct elaborate jewelry. In the 2nd millennium, the Mycenaeans and Assyrians used sard in articles of personal adornment. And in the 1st millennium, the Greeks often chose prase, a dark leek green variety, with chlorite inclusions, which is rarely used in jewelry today. Carnelian and sard were among the varieties of chalcedony preferred by Roman lapidaries.

The frequent choice of chalcedony for personal adornment is partly due to its tough fibrous structure, which makes it very durable and able to withstand the toll of wear and tear on jewelry. But the main reason for its popularity is the attractiveness of its colors and patterns. These attributes usually determine the value of a stone. Among the well-known varieties of chalcedony used in jewelry, chrysoprase is the rarest and most expensive. Translucency is also an important attribute in chrysoprase, as well as carnelian and many types of agate.

Virtually all varieties of chalcedony make excellent beads that are beautiful but sturdy, of all shapes and sizes in a rainbow of colors, monochrome or patterned, smooth or faceted. Polished slices of chalcedony with concentric banding, such as fortification agate, or with dendritic inclusions, such as landscape agate, make striking pendants. Cutting fire agate en cabochon brings out its shimmering iridescence to enhance rings, brooches, and necklace components.

Ancient chalcedony beads. RKL

Chalcedony’s fine-grained texture and hardness (7 on the Mohs’ scale), as well as its fibrous structure, also make it an ideal stone for carving. In the ancient world it was often used for seals because it could be incised with detailed designs that would make sharp, distinctive impressions. In addition, hot wax did not adhere to chalcedony’s fine-grained surface, and it was durable. Chalcedony seals dating to the 2nd millennium BC have been found at the Minoan Palace of Knossos, in Crete. For those same qualities, ancient Egyptian craftsmen often chose chalcedony for carving amulets. Muslim merchants have traditionally favored seals made of carnelian, and the Prophet Muhammed, himself, is said to have owned one.

Throughout history, chalcedony’s fine grain has also made it the gemstone of choice for carving fine intricate designs for cameos and intaglio pieces. Varieties that exhibit sharply contrasting parallel layers are especially desirable—in particular, onyx with its bold bands of black and white, and sardonyx, with its alternating layers of dark red and cream. While the dark layer serves as the background, the raised relief of a cameo or the incised design in intaglio work is carved in the light layer—or sometimes the reverse.

Age-old legends and New Age beliefs have extended chalcedony’s virtues from the stone to the owner or wearer of the stone, from the world of rocks and minerals to one’s personal physical and psychic realm. Thus chalcedony’s strength, hardness, toughness, and durability endow the believer with physical energy, fortitude, stamina, and endurance. In classical Greece and Rome, Olympian athletes and Caesar’s centurions carried or wore this stone as a talisman in the hope it would make them invincible. In medieval times, cups and other vessels were carved from chalcedony not only because of the stone’s beauty but because it was believed to have the power to counteract poisons.

Chalcedony’s many varieties have different attributes that are thought to give them various powers to protect or heal a person, to ward off evil or bring one good fortune. For example, carnelian is believed to give one courage, whether one is going into battle or taking a new uncharted path. Bloodstone is said to protect a person from deception and sorcery. Chrysoprase is thought to strengthen one’s eyesight and, by extension, to shield one from the forces of darkness.

Stones of blue chalcedony were considered sacred by Native Americans, who used them in ceremonies and healing rituals. The cool, placid hues of blue chalcedony are easily translated into the power to calm anxiety and soothe emotions, to alleviate fears and feelings of anger; to eliminate stress and clear the mind, to help one center and restore balance; to become serene and more conscious in thought and speech, and thus improve communication with one’s inner being, the outer world, and the invisible; to become at peace with oneself and all that is around one.

Champleve

An enamel technique, similar to cloisonné, where powdered glass fills depressions in a metal bead, which is then fired to fuse the glass to the metal.

See Also: Enamel Beads Cloisonné Beads

Chandelier

Copper chandelier finding with six loops for dangles. CW

A term used for elaborate earrings or earring components that are reminiscent of fancy light fixtures with multiple shimmering dangles attached to loops and branches.

Charlotte Beads

Also known as "one-cuts" or "true-cuts" these small European seed beads have a single facet. The name generally refers to seed beads size 13 and smaller although it has also been applied to larger seed beads.

Charm Case

A container, usually of metal or leather, which holds a written charm, sacred scripture, or magical substance. Worn throughout India, the Himalayan countries and the Middle East, these containers have also been called amulet cases or prayer rolls, but rarely contain prayers.

See Also: Amulets

Charms

Small dangles such as those used on charm bracelets. Alternately, an objcet believed to influence the spirits or fate. Many beads have functioned as charms throughout history.

See Also: Amulets Talismans

Charoite

Charoite beads. CW

Named after the Charo River in Siberia, this stone is a complex mineral that ranges in color from pale lilac to deep purple. It sometimes occurs with black or gold inclusions and measures 6 on the Mohs scale of hardness. In crystal healing Charoite is known for its ability to help purge inner negativity, dispel bad dreams, and protect from psychic attack. It facilitates the release of unconscious fears and serves as a catalyst for healing.

Chasing

Chasing is a decorative process that involves applying pressure to the front of a metal piece by using a hammer and variously shaped punches to create linear designs on the surface of flat or shaped metal. A smith also uses it to sharpen details and define the design in repoussé work and metal castings.

Chasing is the opposite of repoussé, in that in repoussé work the smith generally applies pressure to the back of the metal in order to raise designs in relief. Chasing is similar to stamping, except that in stamping the smith uses a stamp or a punch with a pattern or texture that he impresses into the metal with a single sharp blow of his hammer. Chasing differs from engraving in that no metal is removed, as it is in the engraving process. A sharp metal instruement is used to cut into the metal. When making hollow metal beads, the smith must complete all work that requires hammering before soldering the two halves of the bead together.

See Also: Engraving Repoussé Stamping

Closeup photography of a Taureg amulet, showing their very exacting chasing with handheld gravers. See Ornament 40/4, 2018. RKL

Chasing Hammer

Chasing hammer used for flattening and texturing wire, as well as riveting. CW

A hammer with a two-sided steel head and a wooden handle. One side of the hammer’s head is a flat disk, which has a broad surface for flattening wire. The other side of the head consists of a ball, which is used for riveting and chasing. High-quality hammers have a handle that is equal to the weight of the head, which gives balance to the tool. You can use a chasing hammer with an anvil or a bench block when working with wire or sheet metal.

See Also: Anvil Bench Block

Chatoyance

From the French for "to shimmer" (and possibly also related to the french for cat) this term referes to a reflected band of light caused by alligned inclusions in stone or glass beads. The common name for this effect and beads that exhibit is is cat’s eye.

See Also: Cat’s Eye Tiger’s Eye

Chequer Beads

Alternate name for early Roman, European, and Islamic mosaic cane beads with square elements folded or fused together.

See Also: Mosaic Beads

Chequer beads, not weathered, possibly same dating as image to the right. Courtesy of B. Elias. RKL

Chequer bead, ca. 100 BCE-100 CE, 2.2 cm long, weathered. Courtesy of Lost Cities. RKL

Cherry Quartz

A pink or reddish dyed quartz or glass that imitates stone. Generally stone names that have two parts are an indication that the material is not what it might seem to be.

Cherry Tomato Beads

Trade name for red European made glass beads popular in East Africa.

European glass beads collected in Kenya from the Masai; those with seed beads were used as earrings? Courtesy of Stephen Cohn. RKL

Chevron Beadmaking

The process of grinding chevron canes to expose the chevron pattern.

Stages in process of wet grinding of chevron glass canes into a chevron beads. RKL

Chevron Beads

Classic antique Venetian chevron bead from the African trade. RKL

Chevron beads are classic examples of the drawing technique used to make glass beads. These beads consist of several layers that are built up before the tube is drawn. Their Italian name, rosetta, refers to the cross section, which looks like a flower or a star as a result of the molten gather being pressed into a mold. After being drawn out, the ends are either pinched, or ground off to show the zig-zag pattern of the original layers. The result is a bead with an star-like chevron pattern of layered colors on each end.

The first chevrons (with seven layers and faceted ends) are believed to have been made in Venice 1480-1580. They were later copied by the French and the Dutch after some Venetian glass beadmakers were enticed to share their trade secrets. More recent copies can be identified by looking for characteristic markings of the molds and by checking which colors of glass fluoresce under a UV lamp.

The most common colors in genuine chevron beads are blue, red and white or green, red and white. More recent chevrons can be found in a much wider variety of color schemes. Chevron beads are still popular collectors’ items in present day West Africa. They indicate prestige and are worn in various ceremonies. They are sometimes even buried with the dead. Alternate names include Paternoster, Rosetta, Star, Sun, and Watermelon.

See Also: Chevron Beads—Contemporary Chevron Beadmaking Chevron Beads From Americas Watermelon Beads

Indian chevron beads before they improved their technique. There are now also Chinese made chevron beads of good quality. RKL

A selection of contemporary Venetian chevrons. RKL

Chevron Beads From The Americas

Small seven layer roughly-ground classic chevron beads from Peru mixed with striped chevrons. These beads were traded by the Spanish throughout the Americas in the 16th century. RKL

Small seven layer chevron beads are increasingly being used to date and map European contact sites in the Americas. They have been found in Florida, Peru and most recently have been used by East Carolina University archeologists to follow Hernando de Soto expeditions thorughout the southest in 1539-41. Beads and other artifacts that have been recovered from excavations related to de Soto’s travels are housed in the Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia.

Chevron Beads—Contemporary

Collection of contemporary chevrons in various color combinations. RKL

A number of American glass bead artists now make chevrons, like Art Seymour and Heron Glass, as well as Venetian artists.

Contemporary chevron bead by Mary Mullaney of Heron Glass. RKL

Chevron Beads—Imitations

Contemporary polymer chevron replica (left) and Prosser imitation chevron, very worn, from the African trade (2.2 cm long). RKL

Since Venetian glass chevron beads were one of the most important trade beads, many attempts have been made to imitate them. The most common method was to lampwork the chevron design onto a wound glass bead. The six small imitation glass chevrons with the design trailed on (shown here) were most likelly made in China. They were in use in Kalimantan, Borneo.

A rare type of imitation used the Prosser method of pressing cold paste in a mold under high pressure, then firing the molded item. The main manufacturer was the French firm of Bapterosses, which began using this technique in the 19th century and also licensed it to bead and button makers in other countries. As is apparent from the bead on the right in the second image, the design is only on the surface. It has become worn on this example from the African trade. The other bead is an imitation made of polymer in the mid-1990s, by the artist Jacqueline Janes.

See Also: Replicas and Reproductions Simulations and Copies Interpretations of Beads

Lampworked imitation chevron beads, possibly Chinese-made, from Kalimantan, Borneo (0.65 to 1.0 cm diameters). RKL

Chinese Beads—Contemporary

Contemporary Chinese porcelain and, on the last three rows, cinnabar beads. All are beads from the 1980s. RKL

In the early 1970s, when trade between the U.S. and China resumed, a wave of vintage beads and ornaments reached our shores. Composed mostly of jewelry and components from the early Qing to just post World War II era, these pieces delighted collectors and designers alike. As the vintage material become scarce, newer beads began appearing. Most repeated traditional designs in materials historically used in China including porcelain, wood, cinnabar, cloisonné and enameled metal, along with some stone and a little glass. By the beginning of the 21st China was exporting massive quantities of manufactured goods all over the world and communist ideology was giving way to capitalist entrepreneurial spirit. Possibly influenced by bead traders who started venturing into China after collecting expeditions to India, Indonesia, and Thailand, the Chinese also began mass-producing beads. They soon eclipsed the Indians as the purveyors of inexpensive lampworked beads that imitated European, Indian, Indonesian, and African designs. By the 1990s the Chinese were also producing intricate mosaic beads and impressive looking chevrons. Blown glass beads and foil glass beads soon followed, crushing the market for the Venetian originals.

A few problems remain to be solved for this industry to truly thrive. Through lack of understanding of the process or due to excessive pressure to produce, Chinese beads are usually not annealed properly. The failure to cool the glass down slowly under controlled conditions creates stresses in the glass that cause a lot of Chinese glass beads to break. The producers could also benefit from some advice on color combining. Finally, many attractive Chinese glass beads have dropped out of production after just a year or two because the vendors flood the market with each new design at ever lower prices thus devaluing the product in the eyes of the buyers and destroying any profit margin for producers and vendors. Slightly higher prices and more limited supply could have kept many styles of beads profitable and in demand indefinitely. The Chinese manufacturers apparently have not yet understood the difference between the market for beads and the market for plastic buckets or cheap electronics where price matters more than quality. The lesson may be being learned with cast metal beads that have begun appearing around 2009-10. Quality appears to be as good or better than many American manufacturers’ and designs are often more appealing to a contemporary audience. Unfettered by any tradition in this arena, shapes and patterns reflect popular designs from Africa, Asia, and Native American traditions along with contemporary influences. Meanwhile, Hong Kong factories churn out literally boat loads of gemstone beads in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes. The perceived intrinsic value of the stones, combined with ever-changing shapes and finishes, along with relatively low prices keeps this segment of the industry perennially interesting.

China has also long since overtaken Japan as the main exporter of freshwater pearls. Clearly China has the resources, technology and manpower to remain a major producer of wide variety of beads for a long time. The question is whether issues of quality and supply can be managed appropriately and whether they can move from effective copying of beads developed by others to evolving original designs.

See Also: Cinnabar, Cloisonne, Porcelain

Chinese Eye Beads

See: Warring States Beads—Ancient Chinese Warring States Beads—Glass Imitations

Chinese Faience Beads

Faience beads were made in China about 1000 BCE, during the early Zhou Dynasty. Later, these evolved to glassy faience beads, examples of which can be seen under bicone beads.

Ancient Chinese faience beads, in bicone and cylindrical shapes, from the early Zhou Dynasty. See Ornament 38/4, 2015. Courtesy of D. Ross. RKL

Chinese Glass Beads

Glass came to China about 500 BCE. Coiled and monochorme Chinese glass beads were widely traded from about 1200 CE to just before WW II. The beads shown here are from the Qing Dynasty and Republic period. Ornament 36/4, 2013 and 37/3, 2014 have good articles on vintage Chinese glass.

Large blue Chinese “Peking Glass” bead, of the type that were traded to Alaska and the Northwest US. RKL

Contemporary Chinese glass beads, which are completely different from vintage Chinese glass. CW

Lapidary-worked Chinese glass, that were Court Necklace components, often of high quality. RKL

Chinese Glass Ornaments

The Chinese glass industry not only produced beads, but also large number of other ornaments, like toggles, archer’s rings and counter weights, which makes Chinese glass such a rich area for research and collecting.

Part of the same vintage Qing Dynasty Mandaring Court Necklace, showing portion of the counterweight. RKL

Large assortment of vintage Chinese glass beads, toggles, archers’ rings, Mandarin hat and court necklace components, a molded belt buckle imitating mutton fat jade and various molded glass ornaments. These objects employed a range of manufacturing processes, including disposable molds, kiln working and lapidary grinding. Note the cased beads and crackle glass bead. Courtesy of Leekan Designs, David K. Liu, the Liu family and Ornament collections. See Ornament 37/3, 2014. RKL

Qing Dynasty glass counterweight from a Mandarin court necklace, that has been drilled and lapidary ground. RKL

Chinese Stone Beads

Chinese jade imitations and carnelian beads and ornaments in traditional shapes. One of the jade imitation is in the shape of Chinese money, at least three are toggles used by men, and the others are probably used for dangles, including two shaped as money. At least four are paneled carnelian beads. RKL

There is a range of Chinese stone beads, of which the most frequently seen are jade, jade imitations, agates, carnelian and turquoise.

Choker

A short necklace worn close to the neck. Length for women is 14-16" and for men about 18".

Christmas Beads

“Christmas beads” from the African trade. Long strands of seed beads and other small striped and monochrome glass beads. RKL

African "Christmas beads." CW

When the African traders who sell these beads are asked why they call them Christmas Beads, the usual response is that they don’t know. Some have proposed that it’s because their bright multi-colors evoke happy and celebratory feelings, so the name remains a mystery.

The beads themselves are not. Typically 36 inches long, the strands include a mix of old and new, plain and striped, seed beads, tile beads, pressed glass round and oval beads, and other small European glass beads of mostly Czech and Venetian origin. In the late 70s and early 80s small chevrons, watermelon beads, whitehearts, greenhearts, and other, more complex early trade beads could be found on some Christmas bead strands. As time goes by and trade networks expand, new beads increasingly predominate, with a few Indian seed beads also beginning to replace some European ones. Although most strands tend heavily towards yellow (an auspicious and desirable color for beads in Africa and China among other places), some tend more towards red and a very few have significant numbers of blue beads. Some strands consist of mostly size 8° seed beads, while others also contain at least 50% size 6° seed beads and other larger monochrome and striped beads.

The term Love Beads is a misnomer when applied to these African strands. Although Love Beads, popular in the 1960s and 70s among the counter culture generation, were also longish strands of mostly small beads, they were created by the wearers and their friends as tokens of love, not bought from African traders who did not begin to arrive on the scene in significant numbers until the mid-1970s. Love Beads, often worn in multiples and sometimes with pendants also tended to be shorter, more monochrome (favoring blues and purples as well as the warmer colors), and included silver lined beads, bugle beads, and other beads not traded to Africa or incorporated into Christmas Beads.

We welcome any additional information about the history of Christmas Beads and their name.

Chrysocolla

An opaque green to blue stone that sometimes looks like very vibrantly colored greenish turquoise. This hydrous silicate of copper is sometimes inter-grown with quartz, malachite, or turquoise. Eilat stone, found north of Eilat in Israel, is chrysocolla inter-grown with both turquoise and malachite.

Chrysocolla occurs in association with malachite in Zaire as well as in Israel. Other deposits are found in Chile, Russia, and in Arizona and Nevada in the US.

Credited with curative powers, chrysocolla was once used for purification.

Chrysoprase

Australian chrysoprase beads. CW

Chrysoprase come from the Greek for “golden leek,” because of its bright spring green color. The vivid coloring of this translucent to opaque form of chalcedony comes from the presence of nickel silicate. Sometimes it also displays inclusions of brown or white matrix. Comparatively rare and valuable, fine quality chrysoprase may be mistaken for jade. Often cut as cabochons and carved into ornamental objects, chrysoprase has also been used in the interior decor of churches and castles.

Mined in Poland since the 14th century, those chrysoprase deposits are now worked out. Today the best stones come from Queensland in Australia. Other deposits are found in Brazil, India, the Malagasy Republic, South Africa, Russia, and the western US.

A medieval poet claimed that chrysoprase held under the tongue of a condemned thief would enable him to escape execution, presumably by rendering him invisible. Holding a quite different view, a theologian associated chrysoprase with Christ’s sternness toward sinners. Since antiquity, however, this bright green stone has commonly been thought to be lucky and bring success. On his eastern campaigns, Alexander the Great carried a “prase” in his belt as a victory talisman.

Cinnabar

Cinnabar is mercury sulfide, which is rarely made into beads. Chinese beads sold as cinnabar are actually lacquer beads colored with the red pigment. Cinnabar beads come in various sizes of round beads carved with auspicious or decorative symbolism and characters. In addition large coin-shaped beads and beads depicting fish, dragons and other creatures can be used as beads or pendants. Recently, all of these styles have begun appearing in blue, green, yellow, brown, and black and off-white in addition to the traditional bright red.

Detailed close up of contemporary large Chinese cinnabar bead. CW

Non-traditional blue colored cinnabar. CW

Various shapes of contemporary cinnabar beads. CW

Citrine

Citrine nuggets beads. CW

Citrine is named for its lemon yellow color. It’s a transparent quartz ranging from lemon yellow through flame orange to golden brown. Natural citrine is rare and usually very pale yellow. Heat-treated stones, which are mostly amethyst, tend to have a reddish hue. The best deposits are found in Madagascar; the biggest, in Brazil; others, in the US, Spain, France, Scotland, and Russia.

Thought to aid digestion and relieve stomach, liver, and gall bladder problems. Also dispels mental blocks and promotes courage, confidence, creativity, clear thinking, and a cheerful outlook.

City Zen Cane

The former name of well-known collaborative team of Stephen Ford and David Forlano, who make polymer jewelry.

See Also: Fimo

Some early mosaic Fimo beads made by City Zen Cane. RKL

Clamp

A clamp can be anything that is used to hold components while making jewelry. It can hold wire while you are using other tools, or it can simply hold the ends of your string to secure your beads when you are in the middle of a project.

Clamshell Disk Beads

Thin, flat, round beads, or disk beads, are crafted from the shells of clams and other marine and freshwater bivalve and gastropod mollusks by peoples around the world using a technique that dates back more than 20,000 years. First, roughly circular bead blanks are chipped from the shell and individually perforated with a sharp stone, an awl, or a bow drill. Then, using a simple mass production system, the beads are strung tightly together on a fiber cord or sinew (or, today, on wire) and rolled against an abrasive stone until they are round and smooth and uniform in diameter.

Clamshell disk beads and beads of other materials that are made by the same method are also broadly called heishi, a Native American term for shell disk beads, which have been made in the American Southwest since prehistoric times when Hohokam trading parties trekked marine shells inland from the Gulf of California by foot. Marine shells from the Florida gulf and Atlantic coasts as well as freshwater clams from the Mississippi were traded hundreds of miles north and westward and made into disk beads by Indian cultures in the Ohio and Illinois river valleys. Similarly some of the earliest beads found in China, India, and eastern Europe are disk beads made of marine shells from distant sources.

Africans make disk beads from various kinds of shell: ostrich eggshell, coconut shell, and the shells of giant land snails as well as the shells of several species of bivalve mollusks. West African beads made from freshwater clams (Unio sp.) are typically about 6 mm. to 12 mm. in diameter and range from beige and pale gray to almost white in color. Traders call them coco blanc (French), in contrast to coco noir, the charcoal to black disk beads made from coconut shell. While many African still make many disk beads by hand, today the rich marine resources of the Philippines are being harvested to produce shell disk beads commercially in a wide variety of sizes in natural and dyed colors.

Clamshell heishi of various sizes from the African trade, some of which are made from the giant land snails of Africa. RKL

Claw Beads

Most claw beads seen on the market are molded Bohemian glass, made for the African trade to represent feline claws, although none are meant to be accurate representations. They may be imitating either actural claws or indigenous-made claws in stone or other materials.

Bohemian molded glass beads for the African trade imitating indigenous pendants of animal claws; one is a glass replica of an agate or carnelian claw. RKL

Claws

Portion of bear claw necklace, Mesquaki culture, Iowa, c. 1865. Note the Venetian glass trade beads used as spacers. Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts. RKL

Claws are widely believed to be extremely powerful amulets, endowing the wearer with the qualities of the animal they come from. In India tradition dictated that the claws be immediately removed from freshly killed tigers to prevent the vengeful return of the animal as a tiger demon that could retaliate against its killer. Tigers bare their claws when attacking, and the Naga warriors and hunters of India displayed their trophy claws as symbols of their strength, courage, and superiority over wild animals. Tiger claws were set in necklaces, and among the Kalyo-Kengyu Nagas, they were attached to the chin straps of helmets to frame the wearer’s face. Claws of pangolins (Indian anteaters) were also used in necklaces that served as powerful protective amulets for Naga shamans.

Throughout India pairs of tigers’ claws were worn as amuletic pendants. They were traditionally set in metal, with their bases joined together at the top and their tips below, pointing away from the center. Depending on the wearer’s financial resources, the setting of these amulets might be made of gold, silver, or base metal, and they might be further embellished with pearls and precious gems, or glass imitations. If genuine tiger claws were not available, they could be represented in metal, then sanctified, and the amulet’s power would be activated with a ceremony. In all these examples, the main function of tiger claw amulets was to deflect any evil spirit that might attempt to harm the wearer. In both north and south India, representations of such amulets adorn stone and metal statues of Hindu deities dating back to at least the 5th century AD. During the late 19th century tiger claw necklaces of less elaborate design also became popular in Great Britain as a type of trophy jewelry.

Bear claws have been worn as ornaments and amulets by Native Americans. Although claws in African adornment are rare today, they were no doubt prized in earlier times. Indigenous peoples have mimicked claws in numerous materials, including wood, bone, horn, and shell. Europeans introduced molded glass replicas as trade beads, which have proved to have enduring appeal. Glass-making centers in Europe sent agents to Africa, India, and the Middle East to bring back samples and information about popular beads forms, which were then replicated and exported to eager consumers in the regions where the forms were familiar.

Clear Quartz

See: Rock Crystal

Cloisonné

Contemporary Chinese cloisonné bead. CW

The cloisonné technique involves creating a design with small cells bounded by soldered wire that keep the colors separate. The individual cells are filled with various colors of moistened pulverized glass, which is then fused to the metal surface of the bead. Grinding and polishing produces a smooth surface. As many as six or more steps are required to produce each bead. China has been, and remains, the main producer of cloisonné beads although the technique was also known in Europe.

See Also: Cloisonné Beads—Antique Chinese Enamel Beads

Various contemporary cloisonné beads, probably of Asian origin. CW

Cloisonné Beads—Antique Chinese

Antique Chinese open-work cloisonné bead. RKL

Among the most desirable Chinese beads are antique cloisonné and enameled ones, especially tabular examples. These round flat beads have dragons and phoenixes on their obverse and reverse sides. Cloisonné beads are shown in both closed- and openwork versions, which are rarer. The surfaces without enamel are plated with silver. As seen in the image, there are four primary shapes. In size, the beads range from 1.9 to 5.1 cm long.

The beads shown here are most likely of pre-World War II vintage. They can easily be distinguished from contemporary beads, made in the People’s Republic of China or Taiwan, by the poorer workmanship the more recent beads. All Chinese cloisonné beads are made entirely of copper, including the cloisonné wire, unlike Western cloisonné work, which usually uses precious metal wire. The Chinese do, however, sometimes gild the metal wire after the bead is completed. The blue bead with the gold dragon is an enameled bead, whereas the raised dragon was made by the repoussé or stamping technique.

See Also: Cloisonné Beads Enamel Beads

Antique tabular Chinese cloisonné bead with image of phoenix. RKL

An array of antique tabular and spherical Chinese cloisonné and enamel beads. Courtesy of Ornament Collection. RKL

Cloves

Cloves are among the materials used in scented beads. Around the Persian Gulf, cloves are strung and worn as necklaces by brides.

Vintage necklace from Morocco of imitation glass coral, vintage Chinese glass beads and cloves, partially restrung. Courtesy of the late M.K. Liu. RKL

Cobalt

Cobalt blue Russian Blue beads, which are facetted drawn beads. These were important trade beads in Northwest US. RKL

A mineral used to create a deep rich blue color in glass beads, also used to color faience.

Cobalt blue pressed glass beads from the Czech Republic. RKL

Coconut Shell Disk Beads

Dyed coconut shell heishi strands from the Philippines. RKL

The hard smooth shell of coconuts are used for disk beads in various parts of the world, now mostly in the Philippines.

Coconut shell disc or heishi beads from West Africa. CW

Coil Beads

Vintage Chinese glass coil beads, exported to Burma, 1.4-4.4 cm long. Courtesy of Elaine Lewis. RKL

Beads resembling short sections of springs, made in China of glass from 9th to 14th Century and especially popular around 1200. These were widely traded. May also have been briefly copied in China during the late 20th Century for export to the west. There are also Islamic versions of coil or segmented beads.

Coiling Gizmo

Coiling Gizmo, a tool for making coiled wire beads. CW

A tool for making coiled wire beads.

Coin Silver

Technically silver with a fineness of .900 (vs sterling at .925) but the term is often used for white metal with silver content as low as 60%.

Collared Beads

Two Indian or Nepalese collared silver beads. RKL

A metal bead, usually round or oval, decorated with an extra bit of material to form a collar around the perforation. These beads were particularly popular in India from about 300 BC to 300 AD and old and new versions can still be found in traditional necklaces of India and the Himalayan regions.

Color Wheel

Color wheel used for finding harmonious color combinations with beads. CW

A color wheel organizes color hues in a circle, showing relationships between colors that are classified as primary colors, secondary colors and tertiary in relation to each other in various kinds of color harmony.

Color-Lined

Color lined seed beads. CW

Color-lined beads—usually seed beads—are made of transparent glass with an opaque colored lining. They are produced in a similar manner to silver-lined beads except the lining solution is a sort of paint in this case. The beads are entirely immersed in the paint solution, then tumbled clean leaving the coloring only inside the hole. The colored paint is subject to fading and can also rub off on the cord.

Clear, colorless glass with an opaque lining produces a sort of three-dimensional look. Clear/black lined seed beads are often call “black caviar.” When the bead is made of colored glass you get a two-tone effect. Imagine aqua/purple lined; yellow/green lined; amber/turquoise lined. White or beige inside lining brightens the outside color.

Combed Decoration

Also known as feathering, ogee, or scalloped decoration, combed patterns on glass beads consist of wavy or zig-zag designs in two or more colors. To produce these patterns, threads of opaque glass of one or more colors are trailed in roughly parallel lines around a softened glass bead of another color, or less often, the threads are laid lengthwise on the bead. The applied threads are then usually pressed into the bead by marvering. Finally, a sharp pointed instrument is drawn through the still semi-molten threads of glass perpendicular to the lines. Similar effects can be replicated in polymer clay beads before the material is baked.

See Also: Feathering, Marvering

Contemporary Indonesian combed glass beads. RKL

Composite Beads

The term composite beads refers in general to beads that are made up of a combination of two or more different materials. Examples include ancient Chinese beads of glaze over a faience core, and Middle Eastern beads that combined stone and glass.

See Also: Warring States Beads—Ancient Chinese Warring States Beads—Glass Imitations

An array of Zhou Dynasty composite beads, decorated with simple and stratified eyes, as well as rosettes; note white or reddish cores, and glaze decorations. These range from approximately 0.5 to 2.0 cm diameters. For additional information, see Ornament 38/4, 2015 and 40/5, 2018. RKL

Cones

Sterling silver cones. CW

Hollow cone-shaped findings used to disguise the connection where multiple strands of a necklaces are knotted or wired together onto a single cord or wire that is attached to a clasp. Cones are usually made of metal but also exist in stone. They may be short and fat, long and thin, or sometimes curved. Cones that are cylindrical with a rounded end are called bullet cones. The line between some caps and cones can blur, but generally a cap is wider than it is deep, while a cone is longer (often much longer) than it is wide.

See Also: Bead Caps

Conso

A nylon thread originally produced for the upholstery industry. The thread was designed for hand stitching and is very strong thread with an even twist. The color range has not changed much over the years and continues to be fairly subtle. It works well for micro macramé, simple or complex beading projects, and bead crochet as well as for other, more complex knotting projects. Despite its relatively thick diameter, Conso can be threaded through beads as small as Japanese delicas if the designer has some patience. Supplemax has recently come to dominate the market for this type of cord with its broad range of vibrant colors.

Conus Shell

Conus shell whorl decorated by sawn lines and drilled holes; these are used as hair decorations in Mauritania and elsewhere in North Africa. These are also seen in metal transpositions. See Ornament 32/1, 2008 and 40/3, 2018. RKL

The shell or portions of the shell of the marine gastropod Conus has been among the preferred shells used for ornaments and trade since about 20,000 BC. By the end of the ninth century BC, conus shell whorls were being decorated with dots or ring/dot motifs. Their use as ornaments continues to the present; particularly striking are the carved conus shell disks from Mauritania. These are worn by the Tuareg, by other classes associated with these nomads, by Berbers and berberized tribes of Morocco. Used primarily as hair ornaments, these carved shell disks are also found in necklaces. While the conus shell has been much copied in porcelain, Prosser moldings, glass and plastic, no copies have been found of the carved examples. These carved whorls can range from 1.0 to 3.4 cm diameters.

See Also: Prosser Beads African Shell Beads

Conus shell disks and hemisphere, and their Prosser and plastic imitations, from the African trade. See Ornament 24/4, 2001. RKL

Copal

Mauritanian copal bead with decoratively reinforced perforations and Tibetan copal inlaid with coral. RKL

Copal is a sub-fossil resin derived from aromatic tree sap that has not fully hardened. It is similar to amber, but much younger, only a few hundred to some 30 thousand years old at most, versus up to 320 million years old for amber. Copal tends to degrade with exposure heat and air. Its surface becomes rough and deeply crazed, shedding white flakes. Although copal can take a high shine and has been used in jewelry, it has been far less popular than amber. East African copal has been exploited mainly for high-quality varnish. Copal from Columbia and the Dominican Republic, which has rich insect inclusions, has traditionally been burned as incense by the Maya and neighboring peoples of the Americas. Copal from both regions has been used to create fake amber with fake inclusions of large insects and even lizards, which has even fooled museums.

During the first great influx of African beads into the United States and Europe in the 1970s, much “African amber” (actually a plastic related to Bakelite) was misidentified as copal. The genuine copal found in Berber jewelry in Morocco and Mauritania may have come from sub-Saharan sources in western Africa. The beads are usually irregularly round in circumference, but unlike the round and oblate imitation amber beads, copal beads usually have completely flat ends. In addition, they are often worn or ground down so that one side of the bead is thicker than the other resulting in a necklace that hangs in a smooth curve without gaps between beads.

Source: David A. Grimaldi, Amber: Window to the Past, 1996.

Copies

See: Simulations and Imitations

Copper Beads

Assorted contemporary copper beads. CW

Being a relatively soft and inexpensive metal, copper has long been popular for making beads and findings. Copper beads are sometimes plated with white metal or silver, especially in India and East Africa. Copper can be combined with other metals to make useful and beautiful alloys. Most notably copper is combined with zinc to produce brass, and with tin to produce bronze. Fine silver, with a purity of 99.9% is for most purposes too soft to be worked. For jewelry, sterling silver—an alloy of 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper by weight—must be used instead. Copper oxide added to glass acts as a coloring agent to produce opaque blue and transparent or opaque red, among other hues.

To the consternation of colonial powers and later local governments in Kenya and other African countries, copper wire has been stripped from rural telephone lines and electrical power grids for use in bead and jewelry making. In South Africa, traditional basket-making techniques incorporating beads have been adapted to use legally obtained telephone wire instead of grasses and reeds. The resulting plates, platters, and bowls of various sizes have proved to be visually exciting and popular imports in the US.

See Also: Alloy Aluminum Base Metal Brass Bronze

Tiny copper beads (1-2mm) from Ehtiopia. CW

Coptic Crosses

Ethiopian Coptic cross pendant. CW

The Coptic Church, traditionally founded by St. Mark in Egypt, was long persecuted after the Arab conquest of Egypt in the 7th century. The Coptic community in Ethiopia has remained stronger than in Egypt and produces a variety of ornaments that, when entroduced to the west by African bead traders, became popular collectors and designers. In Ehtiopia the crosses are typically worn around the neck on a blue cotton cord called a “mateb” which is a baptism gift. Because crosses are a symbol of faith, they are one of the most prized personal possessions in the Ethiopian highlands.

Ethiopian crosses feature a wide variety of styles ranging from simple crucifix shapes to more ornate designs with flared arms, trefoils (three overlapping rings), decorative projections and patterns of interwoven lines symbolizing eternity. In the 19th century, hinges and crowns became more common in the designs because of the influence of European medals. Ethiopian crosses also come in a larger version that is mounted on a staff and used in various religious processions.

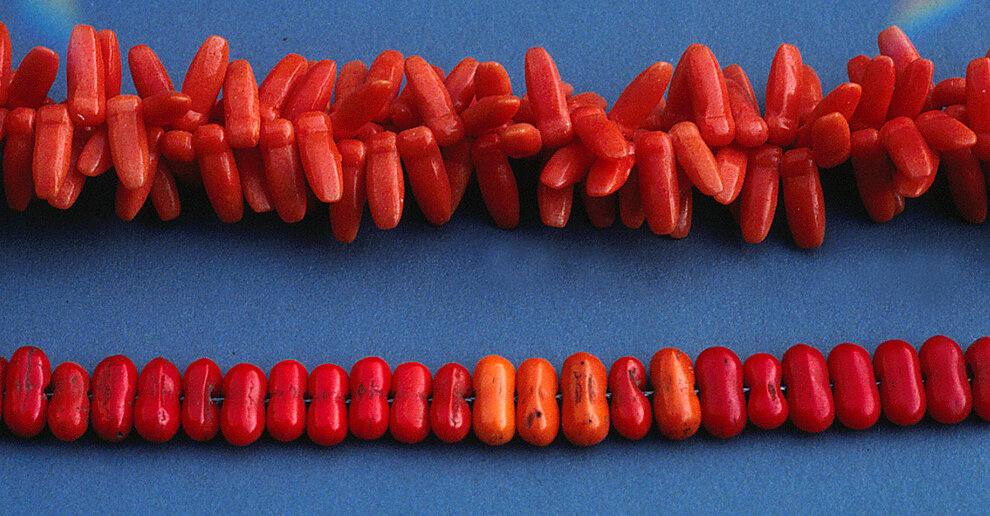

Coral

Various colors of natural branch coral. CW

Coral consists of the skeletons of marine animals called coral polyps, most of which thrive in warm shallow seas and oceans. But there are also cold-water species, such as black coral and bamboo coral, that live in deep water or in the icy waters off the coasts of the Aleutian Islands. Coral polyps build upon one another, eventually creating coral reefs and atolls. The red, pink, white, and blue varieties of coral are made of calcium carbonate, while black and golden corals consist of a hornlike substance called conchiolin.

Precious red coral (Corallium rubrum), which grows mainly in the Mediterranean, is considered an organic gem and has been treasured by cultures around the world for thousands of years. Coral is a particular favorite in Yemen, Italy, Himalayan countries, and the American Southwest. Red and pink coral are found in Japanese waters, in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea and the waters off Malaysia. White coral is found in Japan. Black and golden coral occur in the West Indies, Australia and around various Pacific islands.

See Also: Coral Simulations

Large and very small (about 2mm) natural coral beads, the latter Chinese. Note how the tiny beads are strung together to form a larger bead. RKL

Tiny coral beads (about 2mm) on antique Chinese Mandarin hat ornament. RKL

Coral Simulations

Like any valuable material, coral has been imitated throughout the ages in many materials. The distinction between fakes and simulations or replicas has more to do with the intnent to deceive than with the process or materials used in making the bead. The more realistic the reproduction, the more care and expense usually goes into it’s production and the more likely it can be used to confuse an inexperienced buyer. In some cases unsuccessful replicas can become rarer and more valuable than the original material for a serious collector. On the other hand, popular and widely accepted replicas have very little value for collectors due to their abundance. Although painted ceramic and/or stone beads have been used to copy larger coral branches, glass has been by far the most popular material used for this purpose.

Coral imitations in glass range from individually hand-crafted powder glass versions from Ghana and wound glass beads from Nigeria to mass produced "Sherpa Coral" beads made in Czech factories and shipped to Himalayan countries. Simulated small coral branches can be quite realistic especially when several different shapes are strung together. Other simulations such as the Czech toggle beads (uniform small cylinders perforated in the middle) would not fool anyone. More recently molded plastic coral imitaitons have emerged but these lack the weight, texture, and hardness of glass which so closely mimics coral. As always, financial considerations play a role when buyers or designers choose fake over real. As an expensive organic gem, real coral is out of reach for many people in cultures where it is valued, for example Morocco, Nigeria, Nepal, and Tibet By using a simulated subtitue the general look of traditional jewelry can be preserved and perpetuated even for those who cannot afford real coral. One advantage to using simulations is that the owner doesn’t have to worry as much about loss or theft. Some women will wear fake coral for everyday necklaces, but bring out the real thing for weddings and other important celebrations.

See Also: Coral, Sherpa Coral

Natural branch coral on the left and three glass simulations on the right. Short barrel at the bottom is West African, the other two are European. To varying degrees all show attempts to imitate polyp scars that appear on real coral branches. Courtesy of the late Dr. Boyd Walker. RKL

Two styles of Czech coral simulations in molded glass. The beads on the lower strand are also known as toggle beads and are about 10mm in length. The upper strand with perforations at the end rather than in the middle creates a more realistic effect. RKL

Cori

See: Aggrey Beads

Cornaline d'Aleppo

Large and small Cornaline d’ Aleppo glass beads; the center large bead has been damaged, showing as circular spall marks. These Venetian beads are from the African trade. Note yellow core of larger CdAs. Sizes range from 0.4 to 2.3 cm diameters. RKL

The term cornaline d’Aleppo (French for carnelian from Aleppo) was used as early as 1870 to describe beads more commonly called white hearts, which are made of glass, not carnelian, and have little to do with the Syrian city of Aleppo. They are cased glass beads, made by applying a layer of glass over a core of glass of a different color and/or type. Strictly speaking, cornaline d’Aleppo, refers to compound beads in which translucent red glass is layered over an ivory or white glass core, or sometimes an opaque yellow or even pink core—especially larger beads or beads embellished with lamp-worked eye dots or trailed floral motifs. The beads may be either drawn or wound; some have drawn cores with a wound casing. Although most are small oblates 3 to 5 mm in diameter, they come in a variety of shapes and sizes, including tubes, slices, ellipsoids, barrels, bicones, or spheres, ranging up to 16 mm in diameter.

Sometimes, however, the term cornaline d’Aleppo is loosely applied to other beads of this type. The earliest, first made by the Venetians soon after they mastered the technique of making drawn glass beads, around 1490, are commonly called “green hearts” or, more rarely, “pre-white hearts.” They are always cylindrical with a thin layer of opaque brick red glass over a core of translucent dark green glass, which may appear to be black unless held up to the light.

Not until the early 1800s did the Venetians develop white hearts, when they revived the technique of making rich translucent ruby glass with gold and layered it over an opaque core. By 1860, these master glassmakers succeeded in producing pure white glass for the core, which made these beads even more luminous. During this century of innovations, industrialization shifted much of the manufacture of drawn beads to large factories. First Bohemia and then France began to make white hearts. In the 1890s selenium produced a more vivid orange-red glass, and around 1900 saffron and even blue white hearts appeared. Today white hearts are also made in India and China and come in brilliant shades of green, yellow, orange, cobalt blue, and turquoise, as well as bright red.

The name cornaline d’Aleppo probably arose from the resemblance of the ruby glass white hearts to carnelian. This highly prized reddish variety of chalcedony has been widely traded from South Asia for 5,000 years and doubtless passed through Aleppo, an important crossroads on caravan routes linking Asia, Africa, and Europe. More specifically, it has been suggested that the name refers to legendary banded stones from Aleppo that were believed to have magical powers to heal diseases of the skin.

The likeness of cornaline d’Aleppo to carnelian is more than physical. These cased glass beads have also been widely traded and highly valued. In West Africa, green hearts were bartered for palm oil, ivory, and even slaves. When white hearts were introduced, beads ranging from tiny rikiki, as small as seed beads, to large round “ox eyes were cherished for their color. In Ethiopia and Sudan, 10-12 mm beads decorated with white dots were popular. In East Africa, the Samburu favored deep red ellipsoids, which they strung on elephant tail hair. In Asia more orange colored white hearts were preferred. In the North American fur trade, cornaline d’Aleppo, known by Native Americans as Hudson Bay beads, was the medium of exchange for beaver pelts in the mid-1800s. Known as “the Spanish trading bead” in Guatemala, it was coveted as a coral substitute. Called ventimilla in Ecuador, red white hearts were often strung with silver beads and coins in multiple strands, as they were in other areas in Central and South America. Enjoying popularity worldwide, cornaline d’Aleppo became one of the most sought-after trade beads of all time. These fascinating beads can be found incorporated in traditional jewelry throughout most of Africa, in both North and South Americas, and in India, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and other regions in Asia.

See Also: Carnelian Cased Glass Beads Compound Beads Drawn Beads Green Hearts Hudson Bay Beads Ox Eyes Rikiki Samburu White Hearts Ventimilla White Hearts Wound Beads

Cornelian

See: Carnelian

Cornerless Cube

Carnelian cornerless cube made in Idar-Oberstein for the African trade. RKL

A popular shape in the ancient Middle East. Shown here is an example of a carnelian cornerless cube made in Idar-Oberstein, Germany for export to Africa and the Middle East. During the colonial period at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, bead manufacturing centers in Europe sent agents to Africa to find out which beads were most highly valued. The European bead producers then made reproductions and replicas of such beads to be used in the colonial trade.

Islamic period cornerless cube bead with mosaic decoration, 1.2 cm high. Courtesy of the late Rita Okrent. RKL

Roman period cornerless glass beads with varying degrees of iridescence, or weathering. It is likely these small drawn beads were made into cornerless cubes by facetting, and not marvering. These are 0.7 to 0.8 cm diameters. RKL

Corning Museum of Glass

Located in the historic glassmaking center of Corning, New York, The Corning Museum of Glass houses over 45,000 glass objects, including many beads, which span 3,500 years of glassmaking history. In addition, the Museum is a teaching facility, offering beginning through advanced classes in glassblowing and coldworking. At the core of the museum complex, The Rakow Research Library collects and preserves the world’s most extensive collection of books and periodicals on art and the history of glass, with publications in more than 40 languages.

Cowrie Shell

Crazy Lace Agate

Also known as Mexican agate, crazy lace agate occurs naturally in a range of soft warm tones of cream to gold and reddish brown in swirling patterns. Recently it has appeared on the market overdyed in blue, pink or deep purple. Though attractive, these dyed versions do fade in time and more quickly when exposed to strong sunlight.

See Also: Agate

Crimping Pliers

Crimping pliers are used to squeeze the beading wires tightly into the crimps so that the wire is held tightly. CW

Crimping pliers will consistently create smooth, rounded crimps, while flat nose pliers merely crush crimp beads, leaving sharp edges. In a two-step process, crimping pliers first bends the crimp into two segments to secure the two beading wires; the second step rolls the crimp up in to a tight cylinder to ensure a good connection. Crimping pliers give jewelry a polished and professional look. See our How To section for a diagram and description of the full process.

Crimps

Crimps are small (2x2mm) tubular beads that are used to attach clasps to cable wire beading cords. CW

Crimps, crimp beads, or crimping beads are small, usually tubular, beads of soft metal that are designed to be flattened or rolled around cable wire beading when attaching a clasp. Use chain nose pliers to flatten a crimp or crimping pliers to create a more secure and elegant roll that fastens the clasp to the cord. Crimps come in a variety of metals and finishes including sterling silver, gold filled, 14 karat gold, gold and silver plated, copper, gunmetal (black) and antique brass. Standard crimps are 2mm in diameter, but 3mm crimps are also available in a more limited range of metals. The length of crimps ranges from 2 to 4mm.

See Also: Crimping pliers, Chain nose pliers

Cross of Agadez

Cross of Agadez and related crosses are made by the Tuareg peoples who live in Saharan and Sahelian Africa. While mainly of cast metal, they smetimes utilize other materials, such as wood and plastic.