Breton Shirts

MURPH AND JACKIE BOWYER presenting clothing styles by Mary Quant at The Carlton Hotel, 1967. Photograph by Keystone-France/Thames & Hudson.

“There’s nothing more simple than stripes on a T-shirt,” Auzimour says. “But to do them well and make them perfectly proportioned and beautiful is a difficult thing.”

VINTAGE POSTCARD depicting a French sailor. Courtesy of Robert Butts Collection.

It’s been a summertime staple ever since Coco Chanel and Pablo Picasso frolicked on the French Riviera back in the 1920s. First adopted by the French navy in 1858, the blue-and-white striped Breton shirt—also called the marinière (mariner) or matelot (sailor)—has, fittingly, become an off-duty uniform for men and women alike, worn by everyone from Justin Bieber to the Duchess of Sussex. It’s just one of many modern wardrobe classics descended from nautical dress, including the duffle coat, the blazer, the pea coat, and loafers.

As its name implies, the Breton shirt originated in the Bretagne region in northern France (Brittany to les Americains). Long before the French navy made it part of their official uniform, the traditional knitted pullover with its distinctive wide, plain neck—now known as a boat (or bateau) neck—was worn by civilian sailors, particularly fishermen. Originally made of wool, it provided a warm and hard-wearing second skin on the high seas.

Those Instagrammable contrasting stripes? Their original purpose was to make sailors easier to see in the water if they fell overboard—a maritime practice that dates back to the seventeenth century. But fashion historian Amber Butchart, author of Nautical Chic, explains that visibility wasn’t the only reason for the bold graphic motif. “Using up odds and ends of wool would result in stripes or irregular colors, which wouldn’t have been a problem as the tops were initially meant as underwear, not really to be seen,” she says. “But they had become a significant feature by the time they were adopted into French naval uniform in the mid-nineteenth century.” Butchart dismisses the oft-told tale that each stripe represents a victory by Napoleon’s fleet. “These uniform myths exist in many countries, but they all date from later than the design features they profess to explain!”

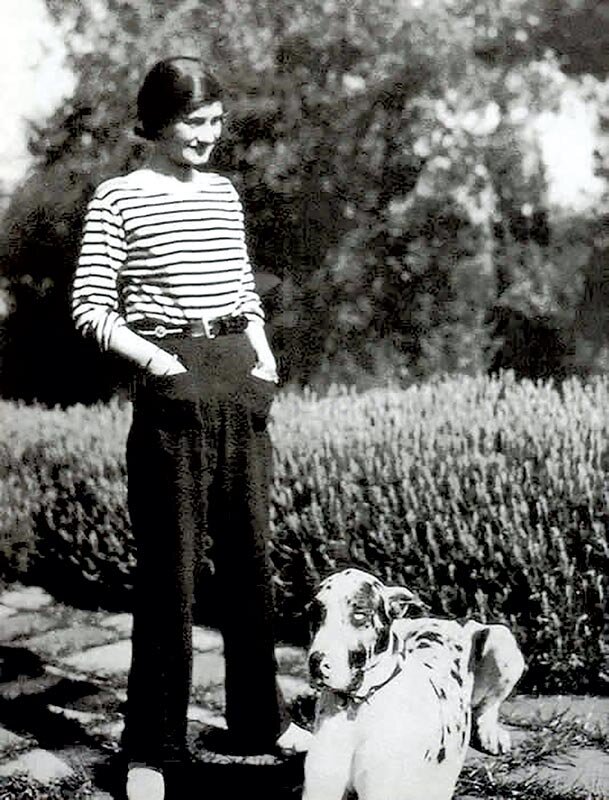

COCO CHANEL posing in a Breton shirt at her villa, 1930. Wikimedia Commons.

So how did the Breton shirt evolve from a functional garment into a fashionable one? Butchart attributes the transformation to a glamorous American couple, Gerald and Sara Murphy, supposedly the inspiration for Dick and Nicole Diver in their friend F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1934 novel Tender Is The Night. “They had a house on the French Riviera that was a hotspot for leading lights of the 1920s,” Butchart says. “Gerald bought a load of tops from a boating store and distributed them among his friends. They quickly became a casual, unisex bohemian seaside style of choice.” The incident and its aftermath makes their way into the novel: Nicole remembers “the sailor trunks and sweaters they had bought in a Nice back-street—garments that afterward ran through a vogue in silk among the Paris couturiers.” Picasso wore sailor shirts constantly when he lived in the south of France, and they can be seen in many of his portraits and self-portraits.

Parisians who didn’t have the time or money to travel to the French Riviera vacationed in coastal Brittany and Normandy. Coco Chanel opened a boutique in the Normandy seaside resort of Deauville in 1913; shortly afterwards, she was photographed wearing a Breton shirt, daringly paired with trousers (for the record, she wore it tucked in). While Chanel undoubtedly helped to popularize the style among landlubbers, making it synonymous with casual luxury, an equally significant factor was mandatory paid vacation time, introduced in France in 1936. “From then on, people were associating Breton shirts with vacation,” says Benjamin Auzimour, managing director of Saint James, the Normandy knitwear company that has been producing Breton sweaters and shirts since the 1850s. “They linked that garment to the idea of freedom and time off.” It’s a chic shortcut to making a staycation feel like a vacation.

In the nineteenth century, the Normandy region was known for two things: sheep and fishing. Saint James “took the wool from the sheep to make clothes for the fisherman,” Auzimour explains. Today, the company has expanded its offerings from wool to cotton jersey, and from striped shirts to striped espadrilles, scarves, socks, dresses, hoodies, and homewares, all produced on state-of-the-art knitting machines rather than by hand. “There’s nothing more simple than stripes on a T-shirt,” Auzimour says. “But to do them well and make them perfectly proportioned and beautiful is a difficult thing.” The width and number of stripes and the distance between them can make or break a Breton.

BRET.ON by Unmade of merino wool; machine-knitted, 2017. Commissioned for “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Photograph by Patrick R. Benesh-Liu.

Click Images for Captions

PHOTO BY CORRIE BOND for Marie Claire Australia, January 2021. Photograph courtesy of Thames & Hudson.

Saint James still supplies shirts to the French navy, but its own retail offerings are tailored to the tastes and lifestyles of modern consumers. The uniform shirt is “difficult to pull off when you’re not a sailor because the boatneck is high and wide, and the fabric is extremely strong but rougher on the skin,” Auzimour says. The company’s bestselling “Minquiers” model—a unisex style—“stays true to the pattern of the stripes, but the cut is regularly changing slightly to accompany trends.”

In recent years, the company has boldly charted new waters, collaborating with partners as diverse as British heritage brand Lavenham, preppy American retailer J. Crew, Swedish graffiti artist André Saraiva, avant-garde Japanese designer Junya Watanabe, and French hip-hop star Orelsan on capsule collections. It produces shirts in rainbow colors and UV-blocking textiles, an innovation that has proved popular with sailors and beachcombers alike. One current offering has heart-shaped red patches on the elbows. A few years ago, Auzimour noticed that the shirts were selling well in California surf shops. “Surfers have always been about respecting nature,” he points out. “They are seamen, in a way!” This summer, the label teamed up with California fashion and lifestyle brand Jenni Kayne on a line of lightweight French linen Bretons for women and kids.

Thanks to its humble, working-class origins, the Breton shirt was taken up as a political statement by French artists and philosophers. It declared one’s rejection of bourgeois pretentions and showed support for the working man and his values, while still managing to look chic. Jean-Paul Sartre, Françoise Sagan and other Left Bank intellectuals wore it in the 1950s, as did Audrey Hepburn when she parodied them in the 1956 film Funny Face. The ultimate rebel without a cause, James Dean, wore Breton shirts; so did Marlon Brando.

Actresses Brigitte Bardot, Jeanne Moreau and Jean Seberg made the marinière part of their gamine garb in the sixties, the childlike simplicity of the stripes playing against their sex-kitten images. Both Andy Warhol and his muse, Edie Sedgwick, wore sailor stripes, he with black jeans and she with black tights; Jackson Pollock and Robert Mapplethorpe were fans, too. Kurt Cobain gave it a grunge twist, pairing it with ripped jeans and battered Converse sneakers. From the moment it first crossed over from functional uniform to fashion statement, the Breton shirt has lived a double life, walking the fine line between the bourgeoise and the bohemian, the patriot and the pirate.

Over the years, leading fashion designers have reinterpreted the Breton shirt in countless styles, materials and color combinations, incorporating ombré, colorblocking and embroidery. Yves Saint Laurent did a floor-length, sequined evening version in 1966. Balmain added dramatic shoulder pads for Fall 2009. Moschino showed a miniskirted version for Spring 2013. Maria Grazia Chiuri branded them with feminist slogans for Dior in Spring 2018. Michael Kors is currently offering a version dressed up with a pussy bow.

Click Images for Captions

DRESS by Junya Watanabe, Prêt-à-porter Spring Collection 2011. Photograph by Andrea Simms/Thames & Hudson.

But perhaps no designer has shown his stripes more often than Jean Paul Gaultier, who reinterpreted the Breton in every one of his collections, including his 2010 capsule collection for Target. His fragrance Le Male comes in a bottle resembling a buff torso clad in a striped shirt. Without sacrificing their nautical nature, Gaultier rendered Bretons in leather, lace, tulle, mohair, feathers, and crochet, and paired them with tartan kilts and leather pants, making them as much a part of his design vocabulary as other iconic styles from French history like trench coats, berets, fishnet stockings, and toile de Jouy.

Gaultier’s mother dressed him in Breton shirts from a young age. (“A lot of us have a grandmother who one day when we were tiny gave us our first Saint James T-shirt or sweater,” Auzimour says.) When he began working in fashion, he adopted them as a uniform so he wouldn’t have to worry about what to wear. “They go with everything, never go out of style and probably never will,” he has said.

For a designer fascinated by androgyny, the sailor shirt was the ultimate unisex garment. But there is another side to the sailor shirt—and the sailor pants Gaultier often paired with it. There is a long tradition of sailors as objects of homoerotic fantasies. With their tattoos, crewcuts and tanned, muscular physiques, sailors represented, for Gaultier, the epitome of male sexuality. His sailor-inspired looks for men put the “naughty” in nautical. Although the designer retired last year, the label’s latest collection includes cropped and mesh versions of his trademark top.

More traditional takes on the Breton shirt can be found this summer at Saint Laurent, Miu Miu, Comme des Garçons, and Céline; there are also budget Bretons by J. Crew, Madewell, Vineyard Vines, and Boden. At a time when “sustainability” and “slow fashion” are industry buzzwords, the Breton’s historical heritage renders it hotter than ever. It may be 150 years old, but it’s still making waves.

SUGGESTED READING

Antonelli, Paola and Michelle Millar Fisher. Items: Is Fashion Modern? New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2017.

Butchart, Amber. Nautical Chic. London: Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Newman, Terry. Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore. New York: Harper Design, 2018.

Blondil, Nathalie et al. The Fashion World of Jean-Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk. New York: Abrams, 2011.

You Might Also Like

Worn On

This Day

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is a fashion historian, curator and journalist, specializing in fashion and textiles. She has worked in these functions for museums and universities around the world, and adds both considerable knowledge, an indubitable perspicacity and a sharp wit to her essays on these insider topics. Her most recent book is The Way We Wed: A Global History of Wedding Fashion (Running Press, 2020). In 2019, her book Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History (Running Press, 2019) was the centerpiece of an article she wrote on how fashion has indelibly printed itself on our historical memory (Ornament, Vol. 41, No. 4). The Costume Society of America has honored her in the recent past with the Betty Kirk Excellence in Research Award.

![LES INDES GALANTES [Romantic India] collection, Lascar dress, Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2000. © P. Stable/Jean Paul Gaultier.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ecd777546870e7084c107b0/1629840934602-KEOMTXW01SIQNS4ERX36/Sailor-Shirts_Les-Indes-galantes-Romantic-India-collection%2C-Lascar-dress.jpg)

![L’HOMME OBJET [Boy Toy] collection, Men’s Prêt-à-porter Spring/Summer 1984. © P. Stable/Jean Paul Gaultier.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ecd777546870e7084c107b0/1629840989671-SAB26DNBJ2YHRZ8D65LS/Sailor-Shirts_LHomme-objet-Boy-Toy-collection.jpg)