Small Wonders

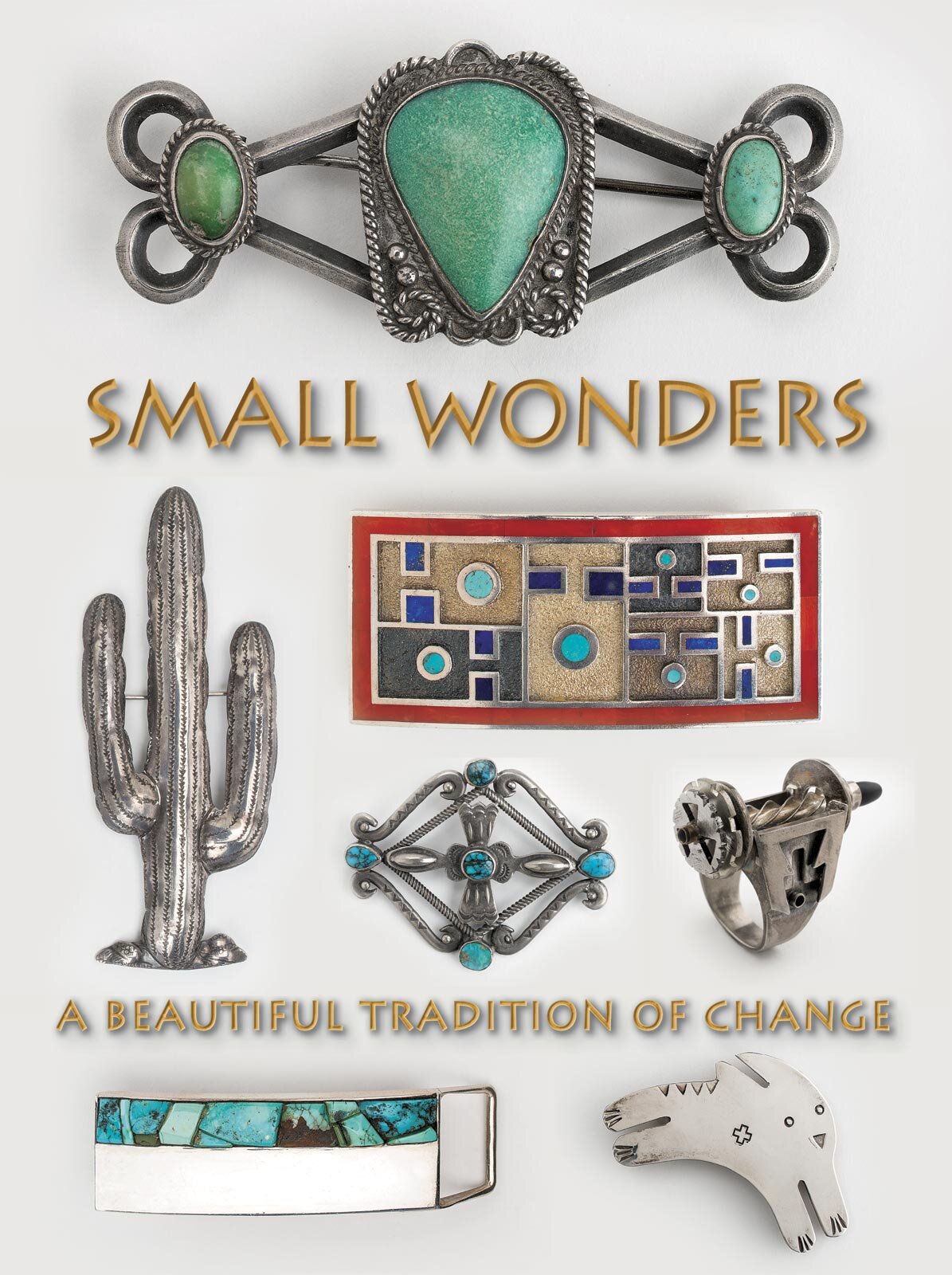

From top to bottom, left to right: NAVAJO BROOCH of turquoise and silver, 1930-1940. Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection. CACTUS PIN by Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) of silver, 1930s-1940s. Gift of Norman L. Sanfield. BELT BUCKLE by Ric Charlie (Navajo) of turquoise, coral, lapis lazuli, and silver, late 1990s. BROOCH attributed to Fred Peshlakai (Navajo) of turquoise and silver, c. 1930-1940. Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection. UNDER FALSE PRETENSE RING by Monica S. King (Navajo/Akimel O’odham) of jet, nickel silver, steel, and brass, 2000. Gift of the artist. BELT BUCKLE by Charles Loloma (Hopi) of turquoise and silver, c. 1969. Gift of the Family of Kenneth Bevry. RABBIT PIN by Jan Loco (Warm Springs Apache) of silver, 1999. Gift of Marcia Berman.

Can a ring be more than just an ornament? Can it have movement? Can it make a social statement? Can it have hidden elements just for the wearer? Of course, all of these things are possible. But for Southwestern Indigenous jewelry, this was not the case a century ago. Rings, and other jewelry forms, were predictably made from silver and further embellished with turquoise or coral, shell and at times jet.

There is evidence of Native silverwork before the Civil War. With some experience in blacksmithing prior to working in silver, contact with Mexican plateros in the territory of New Mexico allowed Native jewelers to further develop their skills in silverworking. (1)

Perhaps the best known early artisan was Slender Maker of Silver. A photograph taken by Ben Wittick, circa 1883-1885 shows him holding an expertly crafted concho belt, wearing a silver bead necklace with naja pendant and with a horse bridle nearby. Stunning works in silver, often embellished with turquoise would dominate jewelry production in the Southwest for decades.

The makers of early Southwestern jewelry were aptly termed “silversmiths” as the emphasis in early jewelry was on the metal itself. But, Southwestern jewelers have shown a flair for experimentation that can express elements of the natural world, reveal a sense of whimsy or embody unusual shapes and forms.

Click to Enlarge

FROG RING by Leekya Deyuse (Zuni Pueblo) of Nevada turquoise and silver, 1930. Gift of Mr. C.G. Wallace.

DEER PIN by Lambert Homer Sr. (Zuni Pueblo) of shell, mother-of-pearl, jet, coral, and silver, 1938. Gift of Mr. C.G. Wallace.

RING by Juan de Dios (Zuni Pueblo) of spondylus shell and silver, 1930-1940. Gift of Mr. C.G. Wallace.

The Heard Museum exhibition “Small Wonders,” showing through January 2, 2022, illustrates the creativity and artistry of Native jewelers as seen through diverse works made in metal and stone. One early Zuni jeweler, Leekya Deyuse, was known for his expert lapidary skills. Bears, frogs, birds, and other animals as well as leaves seemed lifelike when carved by his hands. In 1930, he carved frogs of turquoise and bezel-set them in necklaces, bracelets and rings. One oval-shaped ring holds a frog of the same shape. Another Zuni jeweler, Juan Di Dios, carved the shape of a foot from spondylus shell and made it a setting for a ring as well. Though these subjects seemed unusual for ring settings, they illustrate the whimsical nature and the skilled abilities of the artists who created them.

Native jewelry dramatically changed in the 1960s. Freedom to experiment was in great part due to the efforts of Hopi artist Charles Loloma. In 1939, as a young man of 17, Loloma traveled away from his village of Hotevilla to assist with mural painting at the Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco. His work as a muralist was interrupted by his military service in World War II, where in part he was stationed in the Aleutian Islands. After the war, Loloma studied ceramics at the School of American Craftsmen at Alfred University in New York. Returning home to Northeastern Arizona, he taught school for a period of time and then moved in the late 1950s to Scottsdale where he made ceramics at the Kiva Craft Center. While there, he began to experiment with jewelry fabrication. When his friend and colleague Lloyd Kiva New assumed oversight of the newly founded Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe in 1962, Loloma joined New as head of the Department of Plastic Arts. It was at IAIA, that Loloma had a creative breakthrough that would forever change Native jewelry. He made a ring for a colleague and lined the interior of the ring with turquoise and coral to express his concept that everyone has “inner gems.” Placing inlay designs on the interiors of rings and bracelets and on the reverse of buckles and bolo ties transformed Native jewelry. Following two years at IAIA, Loloma returned home to Hotevilla, where he continued to create jewelry and other silver items in unusual shapes and use non-traditional materials. His work would have a lasting impact on the generation of jewelers that followed.

Click to Enlarge

RING by Charles Loloma (Hopi) of Bisbee turquoise and fourteen karat gold, 1980-1990. Gift of Lois and Richard Rogers.

RING by Charles Loloma (Hopi) of coral, pearl and fourteen karat gold, 1975-1976. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Dennis Lyon.

RING by Dylan Poblano (Zuni Pueblo) of various stones and silver, 2002. Bequest of Ann B. Ritt.

Not only did Loloma introduce new materials, he also experimented with a variety of metalsmithing techniques including lost wax casting while offering dramatic changes to traditional casting methods. He made a notable shift in tufa stone casting, a technique in which the jeweler cuts a slab of volcanic stone (tufa) into two sections, carves a design into one side of the stone and pours molten metal into the cavity through a sprue hole. Native jewelers before Loloma would polish the cast silver shapes to make them smooth and shiny. Loloma polished some areas while leaving the rough texture of the tufa impressed-silver on others. An example of this innovation is visible in his 1980s tufa-cast gold ring. Other artists would utilize this technique. In 2012 Navajo artist Edison Cummings cast a ring leaving surface areas rough. To this he added a Candelaria turquoise. Another Navajo artist, Ric Charlie, is also known for his tufa-cast works which he accentuates in different colored-patinas by using liver of sulphur.

Loloma was among the first Native jewelers to use pearls, lapis lazuli, charoite, and other non-traditional materials. At times he inset these and other materials into lost wax-cast silver settings for rings or brooches. Loloma was also one of the first Native artists to use gold instead of silver. One example is a gold ring he made in 1975 with a carved figure in coral that was further accentuated by the addition of a natural pearl.

The acceptance of Loloma’s jewelry innovations by collectors of Native art allowed other jewelers to experiment with new concepts and materials. At the same time, traditional silver and turquoise jewelry continued to be appreciated. One example of an innovative concept is a necklace based on the solar system that Zuni jeweler Dylan Poblano made in 2002. He designed the necklace to contain bands of silver that encircle the neck of the wearer. He carved the planets out of various stones and positioned them at different intervals on the necklace bands. He also made a series of rings that accompanied the necklace.

One of these utilizes a spiral of silver and includes a stone sphere inset with “dots” of various stones. Poblano learned many basic silversmithing skills by observing his mother Veronica in her studio. Veronica Poblano taught Dylan some basic jewelry skills when he was still a young boy. After high school, Dylan attended the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. Veronica Poblano’s work also illustrates individuality as seen in the garnet drusy, pyrite drusy and silver earrings she made in 2007.

Click to Enlarge

BELT BUCKLE (obverse and reverse) by Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bird (Navajo and Santo Domingo/Laguna Pueblo) of Rocky Butte picture jasper, fourteen karat gold and silver, 1980. Gift of Judy and Ray Dewey.

BUTTERFLY PINS by Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bird (Navajo and Santo Domingo/Laguna Pueblo) of Morenci turquoise and eighteen karat gold, 2005.

Collaborating artists Yazzie Johnson (Navajo) and Gail Bird (Santo Domingo/Laguna) have discussed Loloma’s influence on their jewelry designs. The pair is known for their signature thematic belts which are composed of individually-shaped conchos and buckle that address a theme that might range from gardening to pottery or textile designs or a more whimsical topic such as dinosaurs. The couple began using atypical stones at the onset of their careers in the early 1970s, choosing a wide range of agates in addition to quality turquoise and Mediterranean coral. For their buckles, including those on their thematic belts, the couple might place an agate, turquoise or other stone on the face of the buckle and add a design in overlay on the reverse that addresses the theme. They credit Charles Loloma for the concept of including a design that is only for the wearer. Rings, earrings and brooches are among the small works they make in addition to belts, bracelets and a variety of necklaces. In 2007, they made a pair of butterfly brooches in tufa-cast eighteen karat gold with Morenci turquoise.

Click to Enlarge

RING by Richard I. Chavez (San Felipe Pueblo) of coral, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and fourteen karat gold, 1996.

RING by Jesse Monongye (Navajo) of lapis lazuli, opal, coral, jet, dolomite, turquoise, and fourteen karat gold, c. 2000. Gift of the Estate of James Widener Ray.

RING by Carl and Irene Clark (Navajo) of turquoise, coral, jet, shell, and silver, 1980s-90s.

SHATTERED by Colin Coonsis (Zuni Pueblo) of abalone shell, clam shell, pen shell, copper, and silver, 2010.

Another artist with a long career is Richard Chavez from San Felipe Pueblo in New Mexico. Chavez studied architecture in college and worked as a draftsman for an architectural firm. While working and going to college, Chavez began to make jewelry to supplement his earnings, initially making heishi from stones and shells. The architectural firm’s philosophy of simple and elegant designs influenced Chavez’s jewelry designs as he began to work in metal. Now, more than forty years later, Chavez’s jewelry is known for its precision and aesthetic appeal. Chavez personally cuts and polishes the turquoise, coral, black and green jade, lapis lazuli and other stones he incorporates into his work. When polishing, he walks from his studio into the sunlight to see if he has accomplished the sheen he desires for the stones. He tries not to set the stones at night but instead relies upon natural light to reveal if a stone is properly polished. Chavez’s son, Jared, learned to make jewelry by watching his father when Jared was a boy, by receiving instructions from his father, and later through his studies at Georgetown University. Jared’s jewelry emphasizes the metalwork but he also incorporate stones, particularly agates. Jared jokes that in learning to polish stones for his jewelry, he had to learn to polish the Richard Chavez way.

Several artists create work that feature intricate inlay. Jesse Monongye began making jewelry in the 1970s and learned by apprenticing with his father, Preston, an expert metalsmith. Jesse became equally skilled as a metalsmith but also as a lapidary artist. Jesse creates pictorial inlays in his jewelry and one of his best-known designs is of the night sky. Deep blue lapis lazuli or dark jet skies hold planets and comets inlaid in opal, coral, turquoise, and other stones. Navajo artists Carl and Irene Clark are also skilled at creating intricate pictorial inlay, using micro mosaics. A young Zuni artist, Colin Coonsis, has taken the concept of inlay and transformed it into abstracted complex patterns.

CICADA BROOCH by Liz Wallace (Navajo/Nisenan/Washoe) of black mother-of-pearl, ruby, plique à jour enamel, silver, and fourteen karat gold.

New techniques have also been introduced in recent years. Liz Wallace (Navajo/Nisenan/Washoe) has been incorporating plique à jour, one of the most difficult enameling techniques, into her jewelry for two decades. Constructed over a wire foundation without a backing, this technique allows light to shine through the translucent enamel. With plique à jour (French for “letting in daylight”) the effect is a miniature version of stained-glass. Wallace’s cicada brooches with outstretched enameled wings are dazzling simply for their inclusion of the colorful enamels. But, if you look closely at the cicada brooch included here, it is possible to see that the body of the cicada is carefully carved of black mother-of-pearl, which has its own gleaming qualities. Wallace made this brooch in 2005, adding rubies for the eyes and fashioning the legs of silver.

In 2008, Wallace took a natural black pearl, somewhat elongated in shape, and used it to form the body of a wasp in the likeness of a species informally known as “tarantula killer.” The wings are formed of plique à jour, and Wallace placed a small luminescent opal on the back of the wasp, which is held in place by a gold bezel to further enhance the stone. The legs, curved as a wasp would position them while resting on a surface (hopefully, not a person!), were shaped from silver. Wallace utilized several jewelry construction methods to form this small wonder of a brooch which she so meticulously crafted.

OLD BERING SEA FEMALE FIGURE BROOCH by Denise Wallace (Chugach Sugpiaq/Alutiiq) of fossilized ivory, silver and fourteen karat gold, 2001. Bequest of Dr. E. Daniel Albrecht.

Another more recent development is jewelry with parts that articulate. Perhaps the artist who is best known for this concept is Denise Wallace (Chugach Sugpiaq/Alutiiq). Transformation is an important theme in the lives of Alaskan Indigenous peoples, and elements of transformation are evident in Wallace’s myriad works. Pendants of silver masks are hinged to lift and uncover carved ivory faces below. Arms articulate and sections open to reveal smaller figures that can be worn separately as brooches. Wallace incorporates fossilized ivory into her work and at times delicately incises details of facial features, clothing or other designs onto the ivory to enhance the work and pay tribute to the scrimshaw artists who worked decades before her.

Monica King (Akimel O’odham/Navajo) created a ring with articulated parts for her 2000 Master of Arts degree. King’s ring also is embedded with social commentary. She addresses coal mining in the Navajo homelands. The ring contains a drill that moves. King uses local jet to represent coal and placed it at the tip of the drill. On one side of the ring there is a depiction of a traditional Navajo home and an indigenous face is on the other. The drill separates the home and the Native person. King titled her work Under False Pretense.

Artists have also used humor and whimsy in their jewelry and metalworks for decades. One of the early silversmiths from San Ildefonso Pueblo, Awa Tsireh, who was also known as Alfonso Roybal, spent summers in the 1930s making jewelry at the Garden of the Gods Trading Post in Colorado Springs. Awa Tsireh was also a talented painter and the first Southwestern painter to receive national recognition. The sense of whimsy in some of his paintings is reflected in the jewelry he made as well. The skunks and cows he crafted from silver seem to step out of his paintings. His work is identifiable by detailed and carefully positioned stampwork.

By comparison, Navajo silversmith Norbert Peshlakai carries on Awa Tsireh’s tradition of great stampwork and whimsy with his own flair. Often, Peshlakai has fun titles for his works as well. Two of his brooches represent dogs, one of which he titled Watch Dog and put an image of a clock on its collar. Peshlakai was one of the first Native silversmiths to make silver seed pots around 1975-1976.

He fashioned these from two impressed discs that he soldered together to form a sphere. He left an opening at the top of the jars and embellished them with intricate designs. Peshlakai creates his own dies or stamps and often uses multiple stamps to create a single animal or pattern.

Shawn Bluejacket (Royal Shawnee) has also created whimsical items from silver that include houses fully equipped with slides or miniature tables and chairs. She refers to these as “boxes” as each acts as a small container. She paints the silver in bright colors, which increases their playful appeal. One of the miniature tables is hinged and when open reveals a bundle of carrots.

These are just a few of the imaginative small works made by Native artists today that illustrate talent, skill and creativity.

SEED POT by Norbert Peshlakai (Navajo) of silver, coral, turquoise, shell, jet, and sugilite, 1992. Gift of Norman L. Sandfield.

FOOTNOTES

1. Personal communication Robert Bauver 7/22/2021.

SUGGESTED READING

Adair, John. The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1944.

Bedinger, Margery. Indian Silver: Navajo and Pueblo Jewelers. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973.

Chalker, Kari, ed. Totems to Turquoise: Native North American Jewelry Arts of the Northwest and Southwest. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2004.

Cirillo, Dexter. Southwestern Indian Jewelry. New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

—Southwestern Indian Jewelry: Crafting New Traditions. New York: Rizzoli, 2008.

Pardue, Diana F. The Cutting Edge: Contemporary Southwestern Jewelry and Metalwork. Phoenix: Heard Museum, 1997.

—“Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bird. Aesthetic Companions.” Ornament, Volume 30, No. 3, 2007: 42-47.

—“A New Era in Jewelry. Forging a Future.” Ornament, Volume 31, No. 2, 2007: 48-51.

—“Bolo Ties. Contemporary Neckware of the West.” Ornament, Volume 35, No. 4, 2012: 32-37.

—“Richard Chavez. Meticulous Geometry.” Ornament, Volume 40, No. 4, 2018: 32-37.

Click to Enlarge

SKUNK PIN by Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) of silver, 1930s-1940s. Gift of Norman L. Sanfield.

WOOF BROOCH by Norbert Peshlakai (Navajo) of silver and fourteen karat gold, 2005.

TARANTULA KILLER BROOCH by Liz Wallace (Navajo/Nisenan/Washoe) of black pearl, opal, plique à jour enamel, silver, and fourteen karat gold.

MINIATURE TABLE AND CHAIRS FROM THE BEAU MONDE SERIES by Shawn Bluejacket (Shawnee) of acrylic paint, silver and eighteen karat gold, c. 2000. Gift of Carol and Saul Cohen.

You Might Also Like

Richard Chavez

Diana Pardue is Chief Curator at the Heard Museum, where much of her work has been with Native American jewelry. Her publications include Symmetry in Stone: The Jewelry of Richard I. Chavez (2017), Awa Tsireh: Pueblo Painter and Metalsmith and Native American Bolo Ties: Vintage and Contemporary Artistry (both co-authored with Norman Sandfield in 2017 and 2011 respectively), Shared Images: The Innovative Jewelry of Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bird (2007), Contemporary Southwestern Jewelry (2007), and The Cutting Edge: Contemporary Southwestern Jewelry and Metalwork (1997). As a staff member at the museum, as well as perennial attendee of the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Pardue has an intimate familiarity with many in the Native American artist community. Recently she and Heard Museum Assistant Curator Velma Kee Craig curated the exhibition “Small Wonders,” which includes more than two hundred forty small format works of jewelry and objects drawn from the museum’s permanent collection.