Chris Francis

PUMP of artist’s pants, broom bristles, Sex Pistols button, found fabric, dental floss, roofing tar, 2014. The broom bristles used for this piece come from Francis’s shop.

Tinker, Tailor, Shoemaker

Photographs by Noel Bass except where noted; courtesy of Craft & Folk Art Museum.

With every dawning day, that rockstar glamour emerges from a robust shower of hair. Creator Chris Francis bears the resemblance of a raucous musician, of treble-decibel proportions. Deliciously satisfying to meet in person, the shine does not wear off even upon discovering that he is actually a shoemaker.

Born in Kokomo, Indiana, Francis has forged a trail through life, managing that seemingly-impossible task of remaining one hundred percent on. Having migrated from job to job, from working on film sets to skyscraper abseiler, Francis has made his way in the world led by an attitude of embracing the experience and the present moment.

He is no less passionately engaged in his current occupation of shoemaker as his other walks of life. In four years, he has plunged wholesale into a demanding craft, and found room for personal expression that literally overflows like water burbling out the sides of a boiling soup pot.

Francis has been showing in “Chris Francis: Shoe Designer” at the Craft & Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles, and in an agreement with the museum he transported his entire studio into its front window. This arrangement allowed guests direct access to the maker himself as he crafts his shoes. A friend came with me to the museum to meet with Francis for an interview and a lively discussion and debate ensued. Originally from May 24 through September 5, the exhibition, while downsized, has been extended through January 3, 2016, with his studio in the museum window still receiving visitors.

With a background as a carpenter and a clothing maker, among his other occupations, these experiences of working with his hands were integral steps before his current stint in creating shoes. There is a high degree of competence in their construction that no fresh amateur could achieve. It is the seasoning of life experience that provided the grounding to move on to this new stage.

Francis’s journey has been a story of going with the flow in a conscious, and conscientious, direction. One of his comments refers to his making a curriculum for himself, a curriculum of life. Francis attended the Art Institute of Maryland for over a year, but he found prevailing attitudes about types of art and their value in relation to each other stifling. Francis values learning, whatever the source, and he attributes the class in color theory at the Art Institute as being foundational for his sense of shoe design.

Catching the freight train express, Francis traveled, worked and lived across the country for five years. The diverse occupations he took on all played a role in broadening his skillset—“I worked as a tree topper which taught me perseverance,” he reports. “I was a street side shoe shiner in Chicago and in New York, which proved to be a street level business course that taught me humility, and sparked my fascination for shoes. I worked on fishing ships in the Atlantic and the Pacific where I learned knot work and developed a deep understanding for life.” Seeing the vast nets of fish being reeled in, with hundreds to thousands of gasping, dying animals, made Francis consider the world more carefully and compassionately.

When he made the decision to become a shoemaker, Francis threw himself into the effort with both feet first. He went to the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising’s bookstore and studied all the pattern making books until he memorized the formulas. Francis is a dog lover. With his terrier Schnoopy (a beloved family member, source of inspiration and continuous trickster), he would go to the dog park to sew his first shoes. Lacking a leather sewing machine, Francis had to do all the work by hand, and in the beginning there were no proper shoe lasts, so he carved them himself on the dog park bench. He picked up tools where he could, often from other makers in the Hollywood area. “They all have a great deal of attached history,” he murmurs fondly. His big find came in an attic two blocks away from Salvatore Ferragamo’s first shop in Hollywood. The majority of the lasts he now owns came from that discovery.

This road of self-choice has not been easy. Francis has had to surmount many obstacles, from technical issues to lack of tools, equipment and materials. However, knowing this was the road he wanted to tread made matters rather simple. When asked about how he managed, Francis responds, “I just think it was determination. Just not giving in at all. I was told, so many times, what you’re doing is absolutely crazy. One guy told me I’m building a Spruce Goose—he’s like, ‘Quit, you’re building a Spruce Goose doing that.’ See I’ve always had this running joke with Howard Hughes, you know, over that, and all I can say is, ‘The Spruce Goose flew man! And it went to a museum!’ ”

HOMESICK of wood, cotton batting, steel, rubber, leather, paint, 2015. Both Homesick and Comfortable Shoe, Size 7 were made during Francis’s residency at CAFAM.

Francis comes from Kokomo, a small town in Indiana, a factory town, with white steam billowing from the ghostly forest of chimneys. It is the inspiration behind one of his shoes, a logical anomaly where the shoes’ sole is a fluffy white cloud, and the heel and platform the factory buildings, multicolored in greenish-blue hues, with slanted roofs, backed by the exhaust pipe exhaling its deep, vaporous breath. In fact, it is a shoe sitting on a shoe, or rather, clouds floating above the factories. Their name is Homesick, and they are composed of cotton, wood, batting, steel, rubber, leather, and paint.

Like Detroit, which thrived and fell on the rise and fall of the car industry, Kokomo was home to many steel and car manufacturing plants. The 1980s rendered those factories into an industrial mausoleum, and Francis grew up in this steel and concrete graveyard. “As a kid I played in the abandoned factories, the interiors of blast furnaces became time machines or other imaginary scenarios. I was fascinated by these giant machines. My environment shaped me, and gave me a social conscience at a very early age,” he relates. As he became older, his uncle introduced the young Francis to punk, taking him to shows in Chicago and Kokomo, and this musical movement provided a social refuge.

Music plays a fundamental role in Francis’s life. Sounds literally are colors in his mind’s eye; listening to music is as putting paintbrush to canvas. Music becomes visions, visions become paintings, and that ethereal conduit from energy to physicality takes place because of sonic inspiration. One wonders if, despite punk influences, jazz blazes in his soul. The quick paintings that Francis creates as his model for a pair of shoes is like the abstract play between trumpet blare and saxophone flair. They are what happens when musical notes become visual notes. Protoforms lurk within the curves and sharp angles of Francis’s paintings, an effort, as he describes it, to portray the blueprint for transforming something from the first dimension to the third dimension.

Francis’s perspective of the multiple dimensions, as is his knowledge regarding a number of different subjects, is homegrown—he is a person who tries to figure out the world for himself. “I guess the way I thought we defined one dimension was when it’s just a line like this, and a line that has no shading, no illusion of depth, is what I always considered the first dimension, in the sense of drawing. Then once you shade it and add a point of light, and that sort of depth reference, that’s the second dimension, and then once you bring that to the next level, to the ‘third’ dimension, you expand it into the reality. That’s just how I’ve always broken it down.”

This way of viewing the world extends to his method of making as well. “I basically start by attempting to break as many rules as I can possibly get away with. Every shoe is different and involves new sets of probabilities, each with unique structural challenges and material variables. If the shoe is for a client I am usually pretty hand-tied to tradition and I have to follow more of the known techniques of shoemaking,” he explains.

And what shoes does he make? If you were to take someone who absorbed influences from all over the world, and provided him a vast canvas to methodically paint interpretations, variations and experiments, this is what his oeuvre would be. Francis seeks to stretch us beyond labels, and his shoes, although eventually identifiable, do their best in one way or another to undermine our concept of what a shoe should be or is. At least, the successful ones are. He ruefully acknowledges there are a lot of failures among his “babies.”

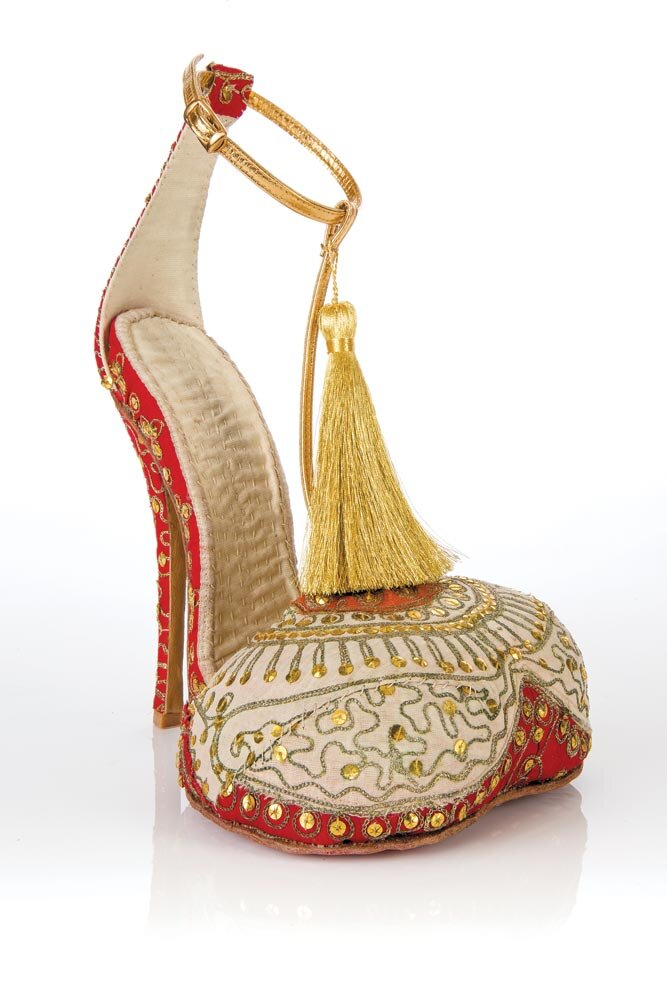

SHOE (Front and Rear) of woven textile, vegetable-tanned leather, wood, hand-brogued leather, linen, cheesecloth, leather, nails, natural glue, 2014.

How to describe one? A Pinocchio’s nose elongated Thousand and One Nights/Scheherazade style into footwear? Or perhaps something fit for an Arabian Jack and the Beanstalk? Reusing textile samples from carpets and wall hangings, the interior is sumptuous gold, with some glittering golden faux snake leather adorning the heel. The divergence between observer and maker can be quite pronounced, however, as we find that Francis’s muse for this piece is the novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne (1759-1767). The characters residing within have various “hobby horses” in their lives, bringing color and that peculiarity of behavior which lead to individuality in their personalities. Francis felt himself relating to the concept of an activity or occupation that helped define one’s identity, and from there these fairy tale shoes took shape. However, it is this diversity of response from his audience which titillates him.

Two rather stately and bold ivory-white, purple, yellow, and red high heels come accented with a deep blue-gray platform that keeps the eye winding from contrast to contrast, all the way up the shoe. Its spiralling sinuous shape wends its way towards the heavens. They belong to the clean, sleek world of modern royalty. However, in a democratized fashion, anyone who can afford them could wear these graceful pumps. There are no court artisans here.

When he really succeeds at breaking “as many rules as he can possibly get away with,” the results barely look like footwear. “So this one, is called Dada Tepepa, and this one’s kind of far out. This was me being very bored with shoemaking, and not wanting to play by the rules of shoemaking. That thought was really absurd, but I started feeling absurd being a shoemaker in the modern world. When I’m making these objects, but you can just go to the store and buy them for twenty dollars, why make these things at all? So I thought, if I’m going to be that absurd, why not make really absurd objects altogether?

DADA TEPEPA of cotton mud cloth from Mali, hand-dyed silk, printed fabric, linen, muslin, canvas, wood, leather, 2015.

“I was watching this spaghetti Western movie called Tepepa, and it was about this Mexican revolutionary single-handedly fighting the government, and I thought that was fantastic. I sort of felt I was like that with shoemaking a bit. I don’t want to make brogues, I didn’t make brogues yesterday, I didn’t wake up making them today and I’ve got no plans to make them tomorrow, and I’m going to make teepees.” He gesticulates towards them—they are like giant, primeval tents encasing the foot. He says with obvious pride, and a slight touch of awe: “They’re wearable. They’re all handstitched. I sat there and handstitched them for hours. That was sort of the insanity of it all. And then doing it twice, that was the ultimate act of insanity. Making a ridiculous object twice.”

However, there are rather wonderful reasons why Francis makes ridiculous objects. “I make the objects I make because they are in the most reasonable format I’ve found to express myself in the world. They have become a true extension of myself and my personality, sharing my awkwardness and whimsical outlook. I often exist more comfortably in my own imagination—most of my creations make sense there. Sometimes I make designs only because they make me laugh and I’m okay with them being laughed at when they arrive in reality—it becomes the function of the object!”

On his ride through time, with multiple stops along the road, Francis has pretty well exemplified his own preachings. Now that he has become a shoemaker, he explains why this particular occupation is fulfilling. “The shoe challenges me and inspires my imagination more than anything else. I see the shoe as a sculptural object capable of infinite possibility, an outlet for invention and a way to be a structural engineer and architect on a small scale. The shoe has also become my means of expression and my format for relaying my interpretations of life, history, sound, and social commentary. Every shoe is a unique situation with changing variables, the odds for failure make for an exciting gamble.”

Although Francis would perhaps revel in being called an iconoclast, he is in fact accepting of all types, from the corporate marketing world to blue collar workers to the urbanites of Los Angeles. What he dislikes is the result of a corporate system: its environmental and cultural impact, and its effect on us as individuals and human beings rather than consumers. His work, and his dedication to the handmade, is a manifestation of his philosophies and principles in action. “A tactile and interactive life is just the most peaceful way I’ve found to exist, so I prefer it. The best way to propagate anything is by example and by offering positive solutions. My positive solution is to be the person you want to be in the world, and live a life that doesn’t abuse others. Live your art or whatever your dreams may be and create a world that you love. Be yourself and let others be themselves and invent your own way of life.”

Click for Captions

Related Reading

THE STUART WEITZMAN

COLLECTION OF HISTORIC SHOES

Patrick R. Benesh-Liu is Associate Editor of Ornament and continues to find time to enjoy craft in between writing, travel and tech support. This issue, he is delighted to debut Chris Francis, shoemaker extraordinaire, currently parked in the front window of the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles. He found in Francis a patient and curious person who revels in the self-expression and exploration the artist achieves through crafting shoes. In addition to this report, he also provides a zesty compilation of the latest craft News, where you can find out what is happening with art-to-wear in your local corner of the world.