TUAREG JEWELRY

OLD AND WELL-EXECUTED SILVER TCHEROT OR AMULET, of silver sheet and wire, is strung on braided leather, possibly goat hide; it is from Agadez, Niger, and the amulet is reputed to be one hundred and fifty years old. The front, three-stepped engraved portion is one piece of sheet forged on the anvil, with a small dome in the center; the back is cold-joined to the front by folding over the edges. A considerable number of tcherot utilize a three-stepped configuration. It is finely engraved on the front and is 11.0 cm long, not including the wire loops. Such amulet cases are worn as pendants by both Tuareg women and men, depending on their drum group, and multiple, horizontal tcherot are worn on the tagelmoust, the wrapped veil of indigo-dyed cloth worn by all traditional adult male Tuareg. Photographs by Robert K. Liu/Ornament, except where noted.

CRAFT

AS

LIFESTYLE

Like many indigenous peoples, the nomadic Tuareg treat craft as an integral part of their lifestyle. Whether functional or for personal adornment, all their craft, in metal, leather or composite construction (like wood, leather and metal for camel saddles) are made by both men and women, the latter working primarily in leather. While it is not certain that all Tuareg women can work leather, the making of jewelry, weapons, other items like saddles, are done by their male inadan wan-tizol, which include smiths, jewelers, woodworkers, and leather-working castes. But according to Cheminée (2014), who has studied with Tuareg smiths for years in West Africa, the individual enad can also work either wood, leather, soapstone/gypsum, or metal (pers. comm., 2/2019). This is very similar to how many Native Americans can transit easily from one form of art to another. With Native American jewelers, there is another parallel, in that their tools and workshops are also much more simple then contemporary Western jewelers. In the West, craftspeople are known more for concentrating on one medium or having expertise mainly in one craft, like jewelry or weaving.

Numbering over two and a half million, Tuareg are now undergoing many changes, as a result of drought, warfare and other socioeconomic factors in the Saharan and Sahelian regions of West Africa. Tuareg live in Mauritania, Mali, Algeria, Libya, Niger, Chad, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Tunisia (Liu 2018a; Seligman and Loughran 2006), as well as Europe and the United States, as a result of the diaspora of many Africans. As pointed out by Cheminée (2014) and Gardi (2006), many Tuareg smiths are either now sedentary or are itinerant throughout capital cities of West Africa, beyond the bounds of the above countries. They also now work and live in Europe and the United States (Benesh-Liu and Liu 2007; Liu 2017, 2018a).

VERY OLD CLE DE VOILE, possibly one hundred seventy to two hundred years old, from respectively Tamangaset and Hoggar, Algeria, to decorate tents of nobles, 25.5 and 32.0 cm long. Made of silver/white metal, copper, brass and ebony, these are as finely crafted as their jewelry.

LEATHER KORAN HOLDER, beautifully decorated with colored leather like the dagger scabbard, with small metal elements; from Agadez, Niger; holder is 13.0 cm wide. Many of the decorative motifs are similar to engraved motifs; actual Koran holder is punched/embossed. The same type of braided and tasseled leather is used on their jewelry.

DAGGER, KEL DENNEG, NIGER, about one hundred years old, 18.0 - 20.0 cm long; primarily ceremonial, and worn on the inside of the left forearm of males (Spring 1993). It is made of silver, copper, steel, leather, and possibly ebony; beautifully crafted, both hilt and blade are engraved, as shown in inset.

LEATHER PURSE, decorated with metal elements, punched and hand-scribed lines, using a knife-like tool, from Ingall, Niger. Leather purse is worn but was probably colored with similar red/green as adjacent Koran holder, 15.2 cm wide. These same colors were also sometimes used on their jewelry but are often too faded to be detected (Liu 1995a, 2018a). Photograph by Christine Benson.

While this article concentrates primarily on classical jewelry, with some examples of swords, household items like tent weights and leatherwork, it is apparent that many common motifs or styles, techniques, shapes and colors pervade all their craft. Tuareg smiths or jewelers employ the largest array of metals and other materials among African jewelers: silver, nickle, copper, brass, iron or steel, aluminum, metals of unknown alloys, and recently, gold. In addition, wood, plastic, unidentifiable materials are also utilized, as well as stones and European trade items like talhakimt of stone, glass and plastic (Liu 1977, 2018a).

METAL/ABAKA WOOD (Pterocarpus erinaceus) BRACELETS. The brass, copper and silver engraved bracelet has black inlays which may be wood or plastic, and is most likely hollow construction, 9.0 cm wide, from Mali. The three bracelets of silver and abaka wood (often identified as ebony) are 8.0 - 9.0 cm wide, with the inner side silver-lined, from Boutilimit, Mauritania, for wealthy Tuareg women. Here the silver is inlaid into or on the wood, along with other metal studs.

The large Benson collection, the subject of this article, is not inclusive of all types of Tuareg jewelry, but it is comprehensive, of high quality and introduces some forms of jewelry not previously described in any of the literature I have read. Aside from the classical forms that are largely of metal, this collection also has ample representation of metal and wood jewelry, one of the hallmarks of Tuareg work, as well as rarely seen metal and stone jewelry, mostly produced for competitions. It does not contain amulets of metal covered in leather, nor those made of iron or steel (Liu 2018). Less than twenty percent of the collection is shown here. Fabricated primarily by forging or casting, this collection has numerous examples of the fine Tuareg surface decorating by engraving, punchwork or ‘punch-repoussé’ and inlay of metal into wood. The wood is often described as ebony but Moulout Algumaret, an Agadez jeweler, states that it is usually abaka wood (Pterocarpus erinaceus), a tree of West Africa now threatened with extinction.

Whether working in metal, wood or leather, Tuareg craft shares a similarity of motifs and techniques, imparting an overall harmony of style and cultural identification, yet showing much regional differences among the drum groups and even families of inadan. For example, while Gabus (1982: 327-330; 457-460) has numerous detail drawings of engraved decorations on Tuareg charm cases, and Creyaufmüller (1982) shows a large number of tcherot, it is very difficult to find close matches among the Benson collection or those I have studied. It is only with tereout tan idmarden or a bride’s pectoral that one can find near identical decorations and construction. To an observer of the Tuareg and other Berber peoples like the Mauritanians, it is striking how their craftspeople treat all materials, whether precious or not, with an equal degree of skilled workmanship. However, gold, with its internationally set high value, is now beginning to be popular, and is generating new types of jewelry but may not be worked with the same degree of detail, complexity and care (Seligman and Loughran 2006).

PECTORAL PENDANT OR TCHEROT/TEREOUT TAN IDMARDEN FOR A BRIDE, from Hoggar/Ahaggar, Algeria, 22.0 cm wide, is virtually identical to one shown in Loughran 2006 (Fig. 7.5, p. 171), except for the sizes and construction of the nail heads. In this example, at least three of the heads are made of layers of silver, copper and brass while the pectoral published in 2006 has only silver nail heads. Instead of engraving, both are punch-decorated from the reverse side, by hammering onto a piece of lead sheet or aluminum in recent times. The six triangles are joined by jump rings, and appear to be filled with lead, if one examines the reverse, where the lead has melted out of the seams. Of the ten or so examples of this type that I have seen, they are often consistent in the similarity of their punched decorations.

PENDANTS WITH PARTIAL NECKLACES of silver, brass and copper, made for Tuareg aristocrats or nobles; Hoggar, Algeria, 14.5 cm wide. Beautifully fabricated by forging, with fine but worn engraving. Note hinges, loops for stringing with leather cord. Those to left are primarily solid metal fabrication, whereas those to the right are hollow construction.

Traditionally, the Tuareg smith’s toolkit is very simple, consisting of hammers, a square anvil with a small hole in the corner for inserting anvil pins, set into the floor or into a wood log, a graver and files. Except for the files, the tools are often made by the smith or his master (Cheminée 2014, Gabus 1982, Liu 2018a). The jewelry shown here are fabricated primarily by forging on the anvil, soldering, filing, cold-connections, and decorated with engraving or punchwork. Some are cast, then worked. In the past, the engraving had symbolic meaning (Fisher 184) but now it may be only decorative (Cheminée 2014). The precision of their virtually flawless techniques (as seen in closeup images), their ability to endlessly vary their designs around common themes and their innovative use of a wide range of materials leads to jewelry that few can duplicate, even with better and more sophisticated tools and techniques. All this was done in ambient light, without the aid of magnifying devices. It is hard not to regard the Tuareg smiths or jewelers as the best in Africa, dependent on few tools but highly skilled in their use and blessed with a jeweler’s eye for preciseness. Some of their work is so delicate that it is hard to determine how it was done, like the inlaying of the serrated metal panels into the wood of the pendants on page 52, upper right.

While the use of electrical devices like buffers is increasing and better tools are becoming available, through services like the Toolbox Initiative provided by jewelers/authors Matthieu Cheminée and Tim McCreight to supply donated tools and materials to West African jewelers, one can easily see that Tuareg jewelry made one hundred years ago can easily match the quality of that made in the 1980s and probably even exceed that made today (Liu 2017), despite the improved tools.

Learning to become a smith or a jeweler is often passed on from father to son, through other family members, or through an apprenticeship. In recent times, many jewelers travel to other countries to learn new techniques and/or to find better business opportunities (Cheminée 2014). Thus, this is a twist on the traditional nomadic life of the Tuareg. Perhaps the most intriguing question is from whom did the Tuareg learn their metalsmithing skills, as fine forging, engraving and the difficult processes of annealing, shaping and tempering of gravers are not seen elsewhere in African adornment, except engraving of a much lesser degree in the Maghreb.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ellen and Walter Benson for allowing me to study their astounding Tuareg collection, acquired over twenty years, all with the help of a Tuareg jeweler from Agadez, Mouloul Algumaret, who spoke no English at first contact but is now fluent. Due to the recent activities of the Boko Haram in northern Mali, which made the Timbuktu-Gao region unsafe, villagers in that region have been selling him their jewelry and other old craft. The jewelry shown in this article were documented by the Bensons in identification sessions with Algumaret. They have also supplied critical literature and images taken by their grandchildren. Our own small study collection of Tuareg jewelry purchased in 1994-95 from Jürgen Busch and Gudrun Kerschna, as well as their gifts, have enabled me to more closely study the personal adornment of this culture, but are of more humble origins. I have had informative conversations with jeweler/author Matthieu Cheminée about Tuareg and other West/North African jewelers. I am still very grateful to Dr. Jan Fahey for obtaining a copy of Gabus’s superb 1982 reference on the Sahara for our library; it remains one of the definitive works on Tuareg and Mauritanian jewelry and techniques, derived from mid-to-late twentieth century French expeditions to Northwest/West Africa.

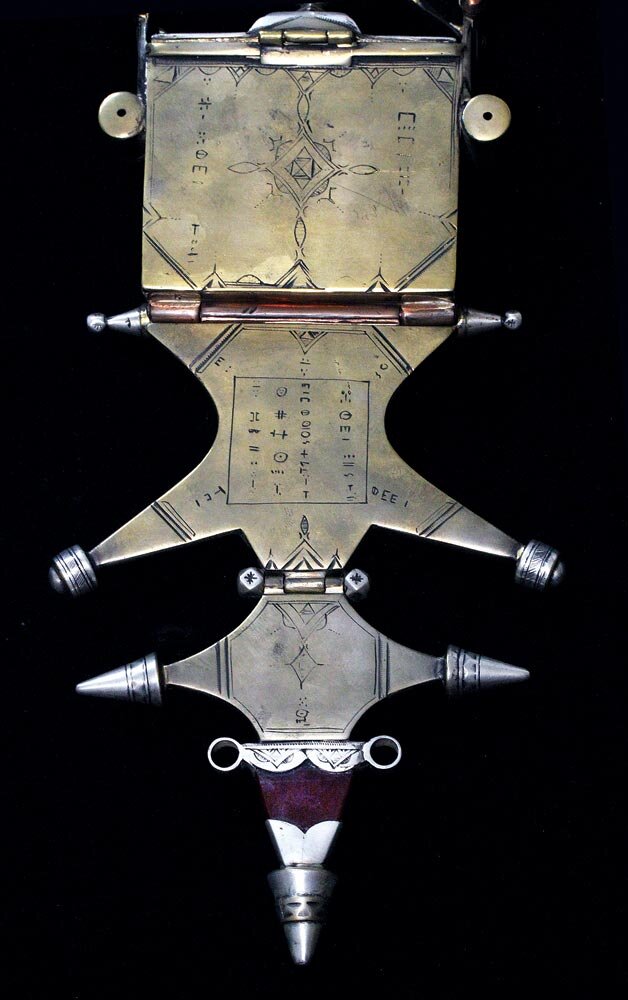

Right: SPECTACULAR AND INTRICATE KORAN HOLDER, over one hundred years old, from Hoggar, Algeria, strung on leather cord, not visible in these images. It has been set with two round cabochons of agate, as well as a broken agate talhakimt, most likely all from Idar-Oberstein, Germany. Of silver inset into abaka wood, it is articulated with three hinges, decorated additionally with brass, 28.0 cm long. Finely and copiously engraved on obverse and reverse, it is most likely signed but I am not able to identify Tifinar signatures. The metal inlays into wood bear resemblance to that of other wood/metal jewelry but this is the most elaborate design I have seen of Tuareg personal adornment, combining almost all their design elements, done in impeccable metalsmithing. Perhaps the quantity and variety of really well-made pieces of jewelry from Hoggar, Algeria, mean that there was considerable patronage from wealthy Tuareg nobles living there in the past. Despite our ability to admire Tuareg techniques and designs, the experience would be so much greater if outside observers could decipher the hidden meanings in their jewelry, as hinted at in Fisher (1984: 194).

REFERENCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bartholomew, T.T. 2006 Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art. San Francisco, Asian Art Museum: 352 p.

Beckwith, C. and M. van Offelen 1983 Nomads of Niger. Abrams: 224 p.

Benesh-Liu, P.R. and R.K. Liu 2007 “Museum News: The Art of Being Tuareg.” Ornament 30 (3): 70-72.

Benouniche, F. 1977 Bijoux et Parures D’Algerie. Collection “Art et Culture”: 85 p.

Bernasek, L. 2008 Artistry of the Everyday. Beauty and Craftsmanship in Berber Art. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University: 125 p.

Burner, J. 2011 Bijoux touaregs. Art des bijoux anciens du Sahel et du Sahara au Niger. Du Fournel: 304 p.

Camps-Fabrer, H. 1990 Bijoux Berbères D’Algérie. grande Kbylie-Aurès. La Calade, Édisud: 139 p.

Chakour, D. et. al. 2016 Des Trésors à Porter. Bijoux et Parures du Maghreb. Collection J.-F. et M.-L. Bouvier. Paris, Institute du monde arabe: 160 p.

Cheminée, M. 2014 Legacy. Jewelry Techniques of West Africa. Brunswick, Brynmorgen Press: 232 p.

Creyaufmüller, W. 1982 Silberschmuck aus der Sahara. Tuareg und Mauren. Galerie Exler & Co.: 93 p.

— 1983 “Agades cross pendants. Structural components & their modifications. Part I.” Ornament 7 (2): 16-21, 60-61.

— 1984 “Agades cross pendants. Structural components & their modifications. Part II.” Ornament 7 (3): 37-39.

Fisher, A. 1984 Africa Adorned. New York, Harry N. Abrams: 304 p.

Fuchs, P. G. Klute und H. Ritter 2002 Tuareg. Eine Nomadenkultur in Wandel. Häusser Media, Museum Künstlerkolonie Darmstadt: 168 p.

Gabus, J. 1982 Sahara. bijoux et techniques. Neuchâtel, A la Baconnièré: 508 p.

Gardi, B. 2006 “Smiths: Makers of Tuareg Identity. Review of Art of Being Tuareg.” H-AfrArts.

Hagan, H. H. and L.C. Myers 2006 Tuareg Jewelry. Traditional Patterns and Symbols. Xlibris Corp: 136 p.

Kalter, J. 1976 Schmuck aus Nordafrika. Stuttgart, Linden-Museum Stuttgart und Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde: 120 p.

Kaspers, F. 2018 “Idar-Oberstein Agate Beads. Stones from Brazil, Cut in Germany, Sold the World Over.” Ornament 40 (3): 64-67.

Leurquin, A. 2003 A World of Necklaces. Africa, Asia, Oceania, America from the Ghysels Collection. Milan, Skira, Skira Editore S.p.A.: 464 p.

Liu, R. K. 1977 “T’alhakimt (Talhatana), a Tuareg Ornament: Its Origins, Derivatives, Copies and Distribution.” The Bead Journal 3 (2): 18-22.

—1987 “India, Idar-Oberstein and Czechoslovakia. Imitators And Competitors.” Ornament 10 (4): 56-61.

—1995a Collectibles: “Mauritanian Amulets and Crosses.” Ornament 19(1): 28-29.

—1995b Collectible Beads. A Universal Aesthetic. Vista, Ornament, Inc.: 256 p.

—2002 “Rings from the Sahara and Sahel.” Ornament 25 (4): 86-87.

—2008 “Mauritanian Conus Shell Disks. A Comparison of Ancient and Ethnographic Ornaments.” Ornament 32 (1): 56-59.

—2017 Ethnographic Arts: “Jewelers at the International Folk Art Market.” Ornament 40 (1): 62-64.

—2018a “Tuareg Amulets and Crosses. Saharan/Sahelian Innovation and Aesthetics.” Ornament 40 (3): 58-63.

—2018b “Easy Closeup Photography.” Ornament 40 (4): 56-59.

Loughran, K. and C. Becker 2008 Desert Jewels. North African Jewelry and Photography from the Xavier Guerrand-Hermès Collection. New York, Museum for African Art: 95 p.

Mickelsen, N. R. 1976 “Tuareg Jewelry.” African Arts 9 (2): 16-19, 80.

Schienerl, P.W. 1986 “The Twofold Roots of Tuareg Charm-cases.”Ornament 9(4): 54-57.

—1988 “Schmuck und Amulett in Antike und Islam.” Acta culturologica 4: 1-146.

Seligman, T. K. and K. Loughran (eds). 2006 Art of Being Tuareg. Sahara Nomads in a Modern World. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University and UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History: 291 p.

Spring, C. 1993 African Arms and Armour. British Museum: 144 p.

Van Cutsem, A. 2000 A World of Rings. Africa, Asia, America. Milan, Skira: 230 p.

Related Reading

Saharan/Sahelian

Innovations and Aesthetics

Robert K. Liu is Coeditor of Ornament, for many years its in-house photographer, as well as a jeweler using alternative materials like heatbent bamboo and polyester films. His recent book, The Photography of Personal Adornment, covers forty-plus years of shooting jewelry, clothing and events related to wearable art, both in and out of the Ornament studio. Chinese faience, composites and glass, both ancient and ethnographic, are among his primary research interests. A frequent lecturer, some of his topics include precolumbian jewelry, prehistoric Southwest jewelry, ancient Egyptian jewelry and the worldwide trade in beads. In this issue Liu writes about an exceptional collection of Tuareg jewelry and other artifacts gathered over twenty years by Ellen and Walter Benson.