Dressed by Nature Volume 43.2

AINU Attush robe (back) of fish bones and tassels, elm bark fiber, cotton appliqué and embroidery, silk, wool, sturgeon scales, shells, bird bones, silk tassels, metal, stone, Japan, 18th century. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Click For Captions

Seldom does an exhibition cover ground so unusual, so unique, that it causes one to gasp aloud. That moment of awe and wonder was present throughout “Dressed by Nature: Textiles From Japan,” recently shown at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. From the first leather fireman’s coat facing you, just as you enter the archway leading to the exhibition, the visual and textural marvels gesture you through a tour of impeccable skill. It begins with salmon skin garments made by the Nivkh people populating Siberia and the Sakhalin Islands. Normally fish skin is something we associate with unpleasant smells; perhaps at best, the bracing sea air and the mist churned up by the crashing waves. Yet in the eyes of the maker who sees it for its positive attributes, it is transformed into a diaphanous, shimmering surface, waterproof, whose brocade inspires thoughts of emperors and empresses rather than fishermen.

It is this head-turning evanescence that permeated and structured the show, in each instance taking what we know of Japanese clothing and flipping it upside down. This exhibition was one of the first of its kind, and the confluence of Ainu, Okinawan and mingei textiles is thanks to Thomas Murray, whose collection comprises the vast majority of the show. Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese and Korean Art, Andreas Marks, speaks with a quiet pleasure about how unusual this exhibition was. Having traveled to Japan to work with local researchers, in both Hokkaido and Okinawa, Marks mentions, “Mind you that such an exhibition has not been staged in Japan before either. Yes, there have been exhibitions of Okinawan textiles or Ainu textiles, but not together and not in combination with mainland folk (mingei) textiles and certainly not in this depth as we did it.”

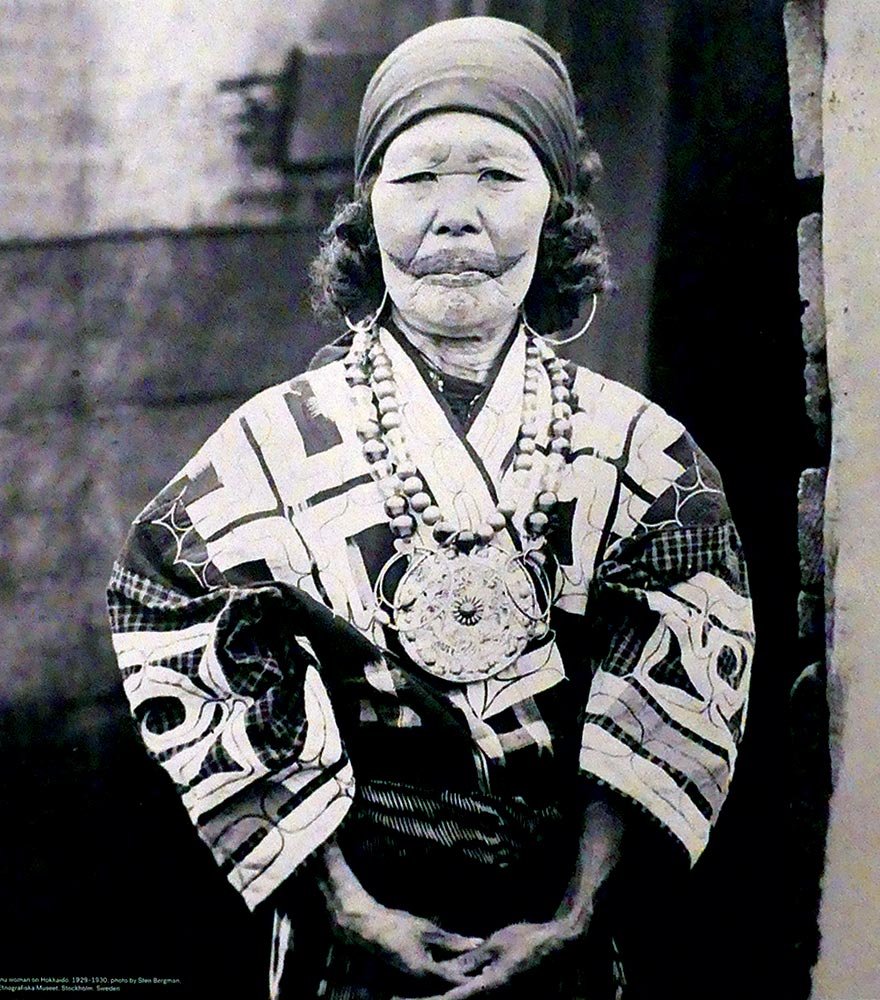

TATTOOED AINU WOMAN wearing a cotton Kaparamip robe and necklace with shitoki medallion. The glass beads may be either Chinese trade goods or Japanese made. Photographs by Patrick R. Benesh-Liu/Ornament except where noted.

Beyond the Nivkh, we travel to see the handiwork of the Ainu, the indigenous people of Northern Japan. Unlike the representational motifs that we’ve come to familiarize ourselves with in Japanese kimonos, the abstract and geometric designs tracing themselves down the front and back of these Ainu garments are bold and wild. Unlike the Nipponese, Ainu clothing features large appliqué panels and bramble-like patterns in contrasting colors, so striking as to make one visually gasp.

A photograph on the nearby wall clues the observer in on a possible origin of these patterns. An Ainu woman stands impassively, meeting the viewer’s gaze. A simple crescent shape adorns her upper and lower lip, hinting at the prevalence of tattooing among the Ainu. The exhibition references other tattoos, usually appearing on the forearm and hands, that echo the patterns that stretch out upon the fronts and backs of their clothes.

There are two clear motifs; one of the Nanai fishskin robes, which are reminiscent of ancient Chinese taotie designs, and the morew motif of the Ainu. The embroidered thorns that manifest at the ends of corners on the angular spiral pattern signal protection. (Fitzhugh and Dubreuil 1999). These appliqué designs were placed at vulnerable points on the body, to deny entry to evil gods. As one looks at these bold designs made out in white, red, yellow, and black, one sees instead magic scrollwork, writ upon the garment to block out evil influences and ward the wearer.

When one realizes this, the garments transform beyond what one could have thought possible. They are gateways, barred shut against the malign, to the sacred spots on one’s body.

As we emerge from the northern reaches of Hokkaido, the Sakhalin islands and the Amur region of Siberia, we find ourselves in Japan again; but not a Japan that we’re familiar with. These are mingei, folk attire that is worn by the lower classes of Japanese society, such as farmers, merchants and itinerants. Bozu, or priest capes hang with an aloof aplomb on their racks, alongside elaborately embroidered horse sashes. Long leather fire coats with emblems emblazoned through resist dyeing stand vigil next to the fire protection garments worn by the rest of the brigade; soaked in water, they provided a temporary haven against the raging inferno. A festive kimono made of humble materials, but delightfully adorned with sea creatures, elevates the common folk who walked the streets of medieval Japan.

Here we see the workhorses that kept Japanese society running; the laborers, the farmers, the itinerants, the merchants, and what they wore. Fine silk is replaced with linen, hemp, cotton, and other fibers. Yet the warm care and celebration of things as simple as safflower dyeing show how simple pleasures led to great things. These garments, colored a delicate peach hue, are semi-transparent, and unlike other kimonos naked of any embroidery or patterning.

Click For Captions

SAFFLOWER-COLORED (benibana) KIMONO of hemp, safflower dye (benibana), made in Yamagata Prefecture, late 19th-early 20th century.

Clothing in Japan for the lower classes was governed by sumptuary laws, similar to how in China only certain badges and emblems were allowed to certain ranks of officials. This stratifying of culture led to a more organized, centralized power structure, where the elites of Japanese society were at the top. As one descended from the position of emperor, or shogun, the materials, symbols and insignia that one could adorn oneself with were limited.

Normally, it is these most sumptuous garments that we find in an exhibition, in constant pursuit of the highest accord. Here we see a horizontal rather than vertical distribution of finery, with some of the best common folk clothing depicting the inventiveness and skill of the peasants and merchants. From the thick indigo-dyed fire hoods and vests that transform their wearers into apparitions, to the simple blue kimono backed by marvelous octopuses, blowfish and flatfish, as well as sea urchins and a lobster, these are expressions of ingenuity and a practiced hand.

The exhibition explored the processes involved in making these clothes. From various dyeing techniques to materials and function, a tapestry of skilled tradition revealed itself. Whether it was with the Ainu people, or the Nivkh, or a patchwork farmer’s coat or the festival kimono, the splendor of each piece, with its crisp, clean lines and bold contrast, reminds us of how wonderful we can appear as human beings.

Let us look again at the fish-skin festival coat by the Nivkh. The exhibition breaks down its cultural influences, where the material comes from, and how it was prepared. Amur carp and chum salmon had their skins removed in one whole piece, then dried, worked and made supple to stitch together the garment. Reindeer sinew is used to embroider surface designs onto the coat, with a dyed neck and sleeve closures heralding from foreign trade. For these far Northeastern peoples, the Manchu and Mongol contributions to style are clear.

Contrast this festival coat, with its kinship to Chinese emperors, with the Ainu attush robes. Rather than the scales of fish, these robes are made from strips of elm bark, turned into fibers. The bark gives the attush robes their distinctive golden wheat color, although some of the exhibition’s most striking examples are ruunpe and chikarkarpe coats dyed a striking dark brown or black. These more supple robes were made with cotton, with bolder use of appliqué.

FUTONJI WITH TAKARA-ZUKISHI MOTIF of cotton, indigo dye; tsutsugaki (freehand resist), 208.3 x 167.6 centimeters, Kansai, Honshu, 19th-early 20th century.

HALF-LENGTH UNDERGARMENT (HANJUBAN) decorated with tigers and bamboo of cotton and silk; katazome (stencil resist), early 20th century.

FARMER’S HANTEN of cotton, tate-yoko gasuri (double ikat), sashiko quilting, 119.3 x 99.0 centimeters, Honsha, 19th to early 20th century. This beautiful yet functional coat would have been worn by farmers during the winter. The Japanese vocabulary clues one into the hierarchy of positions in society. Workwear like this is known as noragi.

Click for Captions

The history of the Ainu with mainland Japanese is complicated. Records stretch back to the 1500s, and reflect the distant and prejudiced view of the aborigines by the Japanese government.

What struck the visitor was how much this exhibition honored the ethnic minorities of Japan, as well as those seldom celebrated; the folk clothing that nevertheless achieves such a high level of skill in the deft hands of the Japanese. One such example is the deerskin leather fireman’s inden kawabaori, a coat with a strange tale accompanying its traditional use. Supposedly, during the Meireki era’s great fire in 1657, two lords who were escaping encountered each other, and although the sparks lit up their attendant’s silk garments, their leather coats were immune. However the knowledge of their fire-resistant properties truly was earned, its spread led to a ubiquity of demand, which was then throttled by the Shogunate via sumptuary laws.

Not only is this handsome coat decorated boldly with smoke resist patterns, but the rest of the garment’s surface, warmed by the smoke, is cut into precise, sharp sleeves and lapel. This both utilitarian and commanding jacket represents the best in Japanese design and technique, boiled down into something the chief of the local volunteer fire brigade would wear.

The exhibition showed a softer, quieter side of Japan, a more complex identity. The word inden in inden kawabaori is India, and represents the technique coming all the way across the ocean. This cosmopolitanism is a facet of Japan which can often be at odds with its xenophobia. Rigidity and fluidity are counterbalancing forces in Japanese culture, and where pressure builds up and overflows, so too does come great creativity. The examples shown reveal how the touch of Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and mainland China affected the rich evolution of Japanese material culture.

Ikat, known in Japanese as kasuri, originated on the continent as well as Indonesia, and migrated eventually to Japan through the Ryukyu Kingdom. This laborious process is an international aesthetic, and the exhibit makes sure to include both clothes that incorporate kasuri, and a robust selection of garments from the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was located on the island of Okinawa. Charting a course through the diverse ecosystem of Japanese sartorial influences is a leviathan task, yet “Dressed by Nature” wove it deftly. From the bozugappa found earlier in the show, special waterproof capes, dwelling in a darkened room after the more brightly lit presentations of the Ainu accessories, to the farmer’s hanten, short winter coats meant for ease of wear as well as something to keep down the bite of the wind, we find examples of kasuri. These tendrils of foreign innovations, brought by the tide of trade, spread like green shoots through the fertile earth of Nippon.

Even the connection of the ikat patterning of the bozugappa isn’t enough, as their design came from observing Portuguese missionaries in the sixteenth century. Gappa came from the Portuguese word for cape, which is kappa.

The Japanese language has a specific vocabulary that tends to be used for integrated foreign concepts, which is known as katakana. Often, a foreign word will be taken, and a Japanese style vowel added to the end of it. So we have “ice cube” to Aisukyubu. Thus does the assimilation of internationalism filter through to the public.

The Okinawan clothing from the period of the Ryukyu Kingdom, 1429 - 1879, wrapped up the exhibit with a profusion of color largely missing from the rest of the show, which tended towards tamer hues, or mixed with broad expanses of dark indigo. A lexicon of Okinawan techniques and textiles paints a rich picture of how indigenous textiles formed their own separate style from mainland Japanese, including ryuso, Ryukyuan robes; bashofu, a fabric made using fibers from the Musa Basjoo plant; and bingata, a form of polychrome dyeing where stencils are used together with resist paste to create crisp, neat designs that burst with vigor.

What the exhibition grasped and communicated in subtle but awed ways is how the woven fabric of Japan, from the Ainu and Sakhalin peoples to the clothing of the Ryukyu Kingdom to the folkwear worn by working class Japanese, had a careful and loving sense of the hand. Marks comments rosily on the remarkably fine aesthetic sense of Murray. “Thomas Murray has an eye for extraordinary quality and these objects are all in very good shape.” Thankfully, museum attendees have responded more than positively to the visual feast. “I learned that people were extremely interested, so much that we had some visitors come back four to five times! Since my picture was in the intro room I had strangers stopping me in the hallways and thanking me for this exhibition... it is very satisfactory for a curator when you receive such feedback and are being told by the visitors for whom we are doing all of this, that the work you put in not only organizing this exhibition but also into acquiring these objects, is appreciated.”

“Dressed by Nature: Textiles from Japan” showed June 25, 2022 to September 11, 2022 at The Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2400 Third Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55404. Visit their website at new.artsmia.org.

SUGGESTED READING

Murray, Thomas. Textiles of Japan: The Thomas Murray Collection. London: Prestel Publishing, 2018.

Fitzhugh, William W. and Chisato O. Dubreuil (eds). Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People. Los Angeles, CA: Perpetua Press, 1999.

RYUKYUAN ROBE (RYUSO) WITH PINE AND SNOWFLAKE MOTIF of cotton; bingata (stencil resist with applied pigments), Japan, 19th century. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

WHITE-GROUND MEN’S FESTIVAL KIMONO of cotton; tsutsugaki (freehand resist), decorated with auspicious motifs made on Tsushima Island, late 19th-early 20th century.

Patrick R. Benesh-Liu is Coeditor of Ornament and a lifelong participant in his parents’ creative journey. From growing up in the Ornament office on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles to his first administrative work in the Vista, California building during high school, Benesh-Liu has had the fortune of being immersed in craft, culture and wearable art. This summer he had the opportunity to see in-person the “Dressed by Nature: Textiles of Japan” exhibit at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (known to Minneapolis natives as the ‘tute’). While the show had received high commendations from a family friend, Benesh-Liu was unprepared for the sheer diversity, quality and rarity of the work on display. Time slowed as each garment radiated a distinct character, and opened a window into parts of Japanese life, both indigenous and otherwise, that is seldom on display. After returning to San Diego, the wheels were set in motion for coverage of this fascinating exhibition.