Portable Universe Volume 43.3

STRIKING ARRAY OF TUNJOS, lost-wax cast votive figures of the Muisca Indians of Colombia.

Patrick Benesh-Liu and I were fortunate to review “The Portable Universe: Thought and Splendor of Indigenous Colombia” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on the last day of its run. This was perhaps the largest exhibition of precolumbian art that has been recently held, with much input from the Arhuaco, one of the indigenous peoples of the lands covered (Columbia and Ecuador). About four hundred objects of metal, ceramic and stone were shown, with a preponderance of gold and tumbaga ornaments. Since the time of the Conquistadors, objects of this metal or its alloys have often been the object of much attention. To the early explorers, only the gold content of these ornaments was of interest, resulting in them being melted down. Imagine if these works of art were still extant, and not just as elemental gold. Columbian and Ecuadorian art is also strong in stone and shell, with the Tairona of Columbia among the best in lapidary skills for hardstone jewelry, and the Sinu for shell ornaments. In this review, the gold and tumbaga artifacts almost overwhelm the senses, and thus receive most of our attention. Starting forty years ago, Ornament published articles on precolumbian necklaces, Tairona beads, tunjos, and the exhibition, “Gold of El Dorado,” as well as having a close relationship with a major dealer in precolumbian South American art, which gave us a solid grounding on similar objects in the exhibition (Davis-Kimball & Twilley 1981, 1982 a,b, Kessler & Kessler 1978, Liu 1982, 1983).

Curiously, the curators made a decision to withhold dating on the labels of exhibited objects, which has received objections from at least one art critic (Knight 2022) and makes me feel as if an important attribute is missing. While time may have a different meaning for indigenous people, dating of these items gathered at considerable effort should have been a part of the historical record of this exhibition.

BREASTPLATES OF A BIRD-MAN with animal helpers, lost-wax cast, from Colombia and MUISCA BIRD-SHAPED one with extended wings, cast and fabricated.

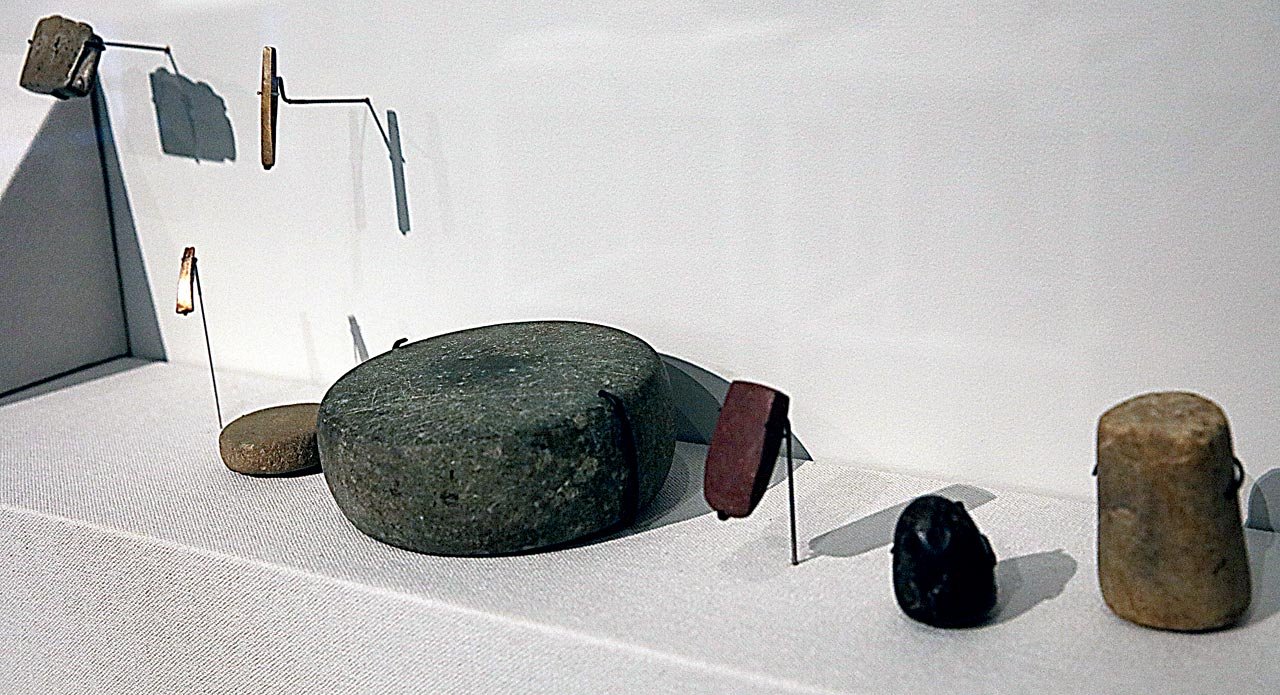

While probably not known to most viewers, the remarkable variety of gold ornaments were primarily lost-wax cast, with some forging and soldering, but all done without the benefit of metal tools except possibly for tumbaga awls, chisels and axes, whose edges had been work hardened to that of bronze. Very few metalworking tools have been found, except those of stone (Liu 1982, 2010). Crucibles, melts and stone anvils and hammer stones, as well as stone matrices are shown in the exhibit, all manifestations of the high degree of skill and sophistication of these metalworkers, utilizing mostly stone tools for forging and repoussé, including the ability to work with platinum (McEwan 2000). Their surface treatments of metal included repoussé, granulation, false filigree, gilding, and burnishing. The difficulty of working metal with stone tools and the amazing skill of precolumbian jewelers has been experienced by this reviewer when he tried to work metal with only stone tools (Liu 2010).

While the gold/tumbaga ornaments are dazzling in their fine crafting and striking appearance, the exhibition displayed other artifacts alongside them to show how such objects were an integral part of the lives of the indigenous peoples. For example, nose ornaments were placed besides ceramic figures which also showed such jewelry being worn. A human figural outline had various types of gold/tumbaga adornment placed on the body, giving the viewer a good idea how their chieftains or cacique would have been adorned. Forty years ago, when I reviewed the exhibition “Gold of El Dorado” at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, there was a similar display (Liu 1982). A full body mannequin wore essentially the same types of Calima metal ornaments, along with feathers, as these bird coverings feature prominently in Precolumbian cultures. A striking feather artifact included in this exhibition demonstrated this. The ability of the Tairona to work soft and hardstones was only seen in a few examples: a long strand of beads, a few shell pendants for grinding lime and some broadwing or stylized bat pendants, still used by present day Kogi. Some of the agate/carnelian beads and carvings on the long strand shown are actually stylized animals, either frogs or grubs/guzano. The importance of grubs in transforming into other forms of insects might have been why such creatures were made in stone, like how ancient Chinese would also portray silk worms in stone. Similarly, this exhibition had transformative powers on the viewers, in how we now view the culture of indigenous Colombian peoples.

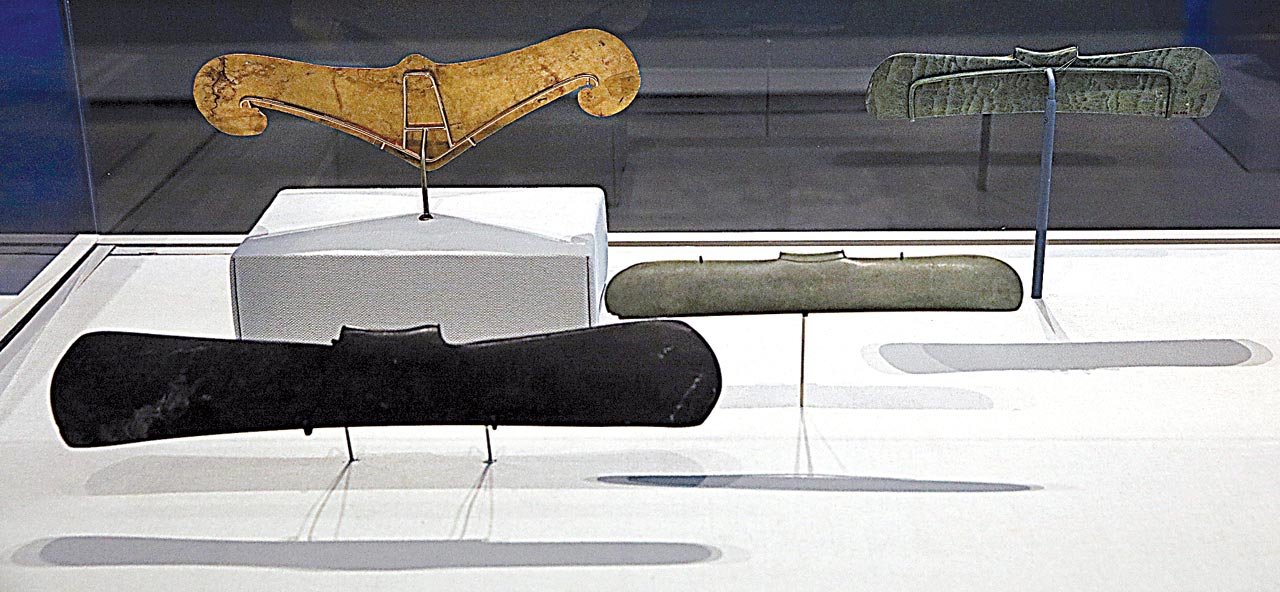

NECKLACE OF SHEET GOLD/TUMBAGA ELEMENTS AND STONE MATRIX TO THE LEFT, which was used by the Muisca to produce wax models to cast these necklace elements (Liu 1982). This was a very useful device to easily make multiple elements, by pressing a sheet of wax over the matrix, then trimmed to size. BIRD FINIAL with beak dangles, of cast tumbaga and fabrication, in early Zenú style of Colombia. The gold/tumbaga ornaments on this page demonstrate well the excellent metalworking skills of the indigenous peoples of Colombia and Ecuador. Contemporary jewelers would have to work hard to match their skill level. DARIEN FIGURE PENDANTS of cast tumbaga, possibly with depletion gilding to bring out the gold content to the surface, and with Quimbaya influences.

CALIMA TUMBAGA ORNAMENTS placed over the outline of a human figure, including a headdress, nose and ear ornaments, pectoral, bracelets, ring, and anklets. TOLIMA ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURE with cast face, partially forged flat sheet body. TUMACO-LA TOLITA CERAMIC MALE FIGURE with nose ornament, necklace and loincloth, from Colombia/Ecuador.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Ken Klassen, Alexander Hirtz and Shari/Earl Kessler for providing access to their collections from Colombia, Ecuador and Panama.

REFERENCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davis-Kimball, J. & J. Twilley. 1981 Tunjos: Muisca Art From Colombia. Pt. I Historical Background. Ornament 5 (2): 6-9.

—1982a Tunjos: Muisca Gold Votive Art. Pt. II Ornament 5 (3): 17-18, 55-57.

—1982b Tunjos: Muisca Gold Votive Art. Pt. III Ornament 5 (4): 12-17.

Emmerich, A. 1977 Sweat of the Sun and Tears of the Moon. New York, Hacker Art Books: unpaginated.

Kessler, E. & S. 1978 Beads of the Tairona. The Bead Journal 3 (3&4): 2-5, 81-86.

Knight, C. 2022 An engaging LACMA show delves into how Indigenous Colombian Cultures think about gold. Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2022.

Liu, R. K. 1982 Review of Gold of El Dorado. Ornament 5 (3): 48-49.

—1983 Pre-Columbian Necklaces, Then and Now. Ornament 7 (1): 2-5, 14-15, 44-45.

—2010 Stone on Metal. Precolumbian Metalworking Techniques and Replicas. Ornament 34 (1): 60-65.

McEwan, C. (ed) 2000 Precolumbian Gold. Technology, Style and Iconography. London, British Museum Press: 248 p.

PRECOLUMBIAN CALIMA CERAMIC CRUCIBLES FOR MELTING METAL, one having a spout, several melted gold/tumbaga buttons, stone anvil, stone hammers for metalworking, and unidentified small tools, possibly chisels? Not photographed were Muisca blow tubes, to increase air flow/temperature when smelting or melting gold/gold alloys in the crucibles. Besides use of blowpipes, often by multiple metalworkers, smelting fires were often placed to catch winds.

LOST-WAX CAST TAIRONA GOLD OR TUMBAGA NOSE ORNAMENT with adjacent fragmentary ceramic pot of male wearing nose ornament and labret or lip plug. It is not clear how such nose ornaments were inserted into the nostril, or whether the septum has to be perforated. LARGE, POSSIBLY FORGED and repoussEd TAIRONA GOLD OR TUMBAGA NOSE ORNAMENT WITH TWO HANDS, with notch for attaching to the nasal septum. Such large and heavy nose ornaments must have not been easy to wear, without considerable discomfort or pain. STONE AND GOLD BROADWING PENDANTS, possibly stylized representations of bats, made in a variety of stones and sizes, some miniature. These are Tairona, from Colombia, although this form of artifact is found around other areas of the Caribbean: Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, and Mexico. The upper protrusion is drilled, to enable the pendant to be worn. The ventral side of the sheet gold ornament is most likely a stylized bat, an animal of ritual importance in many parts of precolumbian Central and South American cultures.

PATRICK R. BENESH-LIU photographing display of ceramic figures, including two stylized tiburon or sharks in foreground and two fish-shaped ceramic graters to the left. STRAND OF AGATE, CARNELIAN AND ROCK CRYSTAL TAIRONA BEADS with the y-shaped beads possibly representing stylized frogs. The Tairona excelled at lapidary work with both soft and hardstones.

STONE AND GOLD SHELL PENDANTS demonstrating transformation of an object into different materials; these were used for grinding lime with coca leaves to extract the alkaloids of the leaves when chewed (Kessler & Kessler 1978). The stone shells are worked by lapidary techniques while the gold shells were probably lost-wax cast. ELABORATE CAST GOLD TAIRONA PENDANT OF BAT-HUMAN with bird head-dress, made by the Tairona. A wax figure is invested in clay; when dry, the mold is heated over a fire while positioned upside down, so that the wax melts out, leaving a cavity. When placed upright, molten gold or tumbaga is poured into this mold, after which the clay investment is broken off, to reveal the cast gold figure, which usually requires sprues/air vents removed, and cleaned up.

Robert K. Liu is Coeditor of Ornament, for many years its in-house photographer, as well as a jeweler using alternative materials like heatbent black bamboo and polyester fibers. His last book on craft, The Photography of Personal Adornment, covers forty-plus years of shooting jewelry, clothing and events related to wearable art, both in and out of the Ornament studio. A lifetime avocation of scale modelmaking culminated in the publication recently of a book on naval ship models of World War II, published in the United Kingdom. Chinese faience, composites and glass, both ancient and ethnographic, are among some of his research interests, as well as Roman mosaic face beads, with the exciting identification of a new type of facial image published in Ornament Volume 42, No. 4. In this issue, he writes the second installment of his two-part article on Courtesan Face Beads, as well as a review of a major exhibition on precolumbian Columbia and photographic advice for craft show applicants.