Freddy Wittop

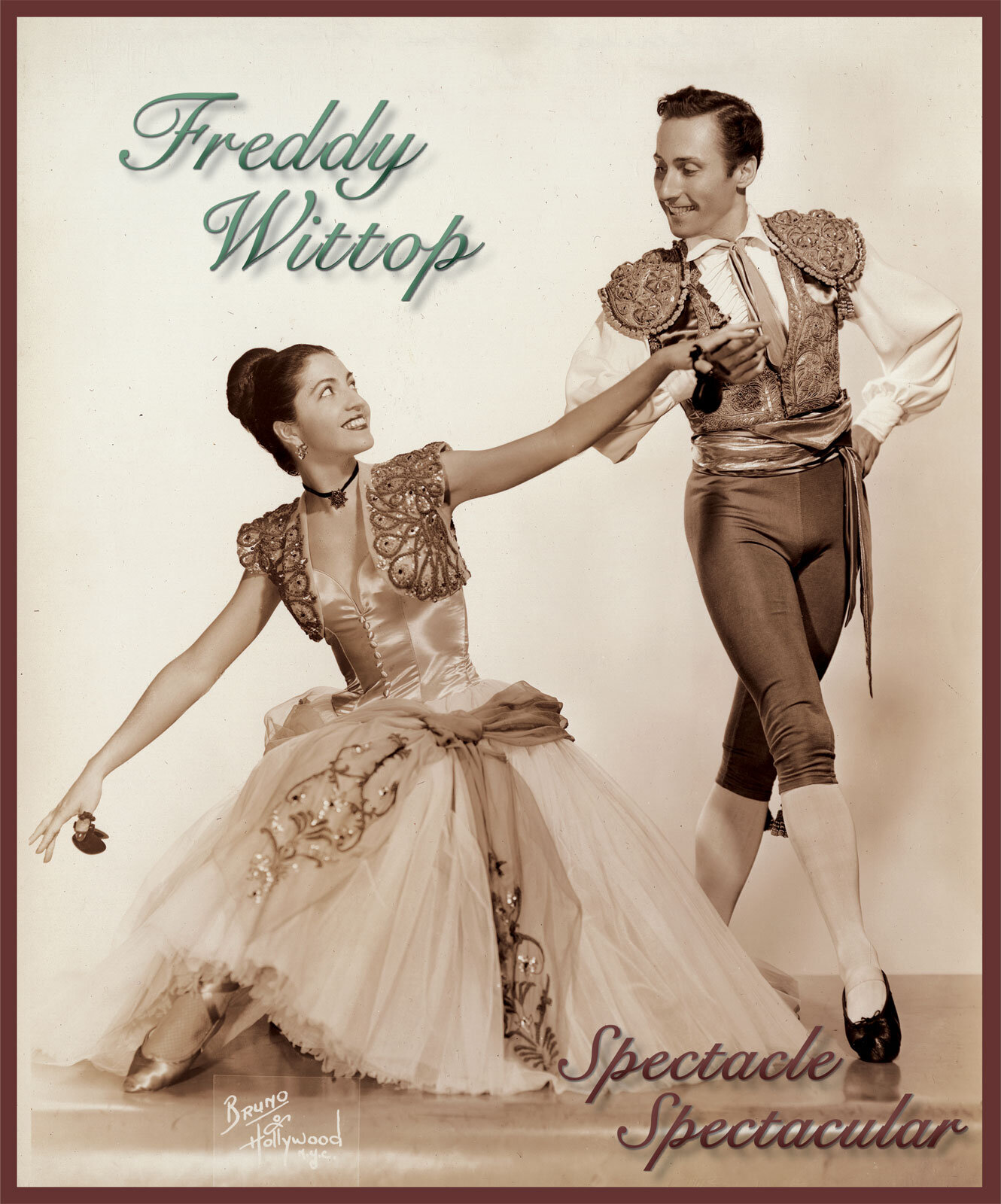

PILAR GOMEZ AND FEDERICO REY, 24.9 x 20.1 centimeters, circa 1952. Photograph by Bruno of Hollywood. Freddy Wittop papers. Images collection of and courtesy of the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Night after night, her crimson hourglass gown sparkled in the theater lights as actress Carol Channing descended the staircase for the title song of Hello, Dolly! With an enormous headdress of bright red feathers punctuating the character’s outsized personality, the costume was pure magic, delightfully demanding attention and adoration. Its creator, Freddy Wittop (1911-2001), was a designer and dancer in the midst of a successful career. Though best known for his costume design work with Broadway, he also gathered lavish yards of silks, tulles, netting, furs, and velvets in enticing colors to dress opera singers, ballet dancers, actors, musical performers, ice skaters, and showgirls for more than sixty years.

LA FRANCE COSTUME DESIGN of gouache on paper, 37.6 x 30.7 centimeters, circa 1933. Paris Music Hall Collection.

Freddy Wittop was born Frederick (Frits) Wittop-Koning in the Netherlands. He moved with his parents—his father was an architect—and sister, who became an opera singer, to Brussels, Belgium, when he was young. He knew from an early age that he wanted to work with clothing and performance, so, when he was thirteen years old, he left school, began ballet classes, and apprenticed with artist and costume designer James Thiriar at the Brussels opera, La Monnaie. There he learned all aspects of costume design, from studying the synopsis of a play to coping with temperamental performers. He saw his first sketches come to life on stage in 1926, when he was fifteen.

Once while at the opera, he met the famous Argentine-born dancer, La Argentina (Antonia Mercé y Luque) while she was rehearsing, and he was captivated by the traditional Spanish dances she performed. She talked with him about studying the castanets, and sparked an interest in Spanish dance that he pursued for the next several decades.

In 1930, Wittop left Brussels for Paris, where he soon began working with the premier costume designer, Max Weldy. Wittop was one of many designers in Weldy’s studio, which created costumes for the famous music halls of Paris, including the Folies-Bergère. These legendary venues epitomized Jazz Age entertainment, with their lively music and dance, extravagant costumes and beguiling nudity. At Weldy’s, Wittop worked with Erté, and later acknowledged that all of the designers there were influenced by Erté’s distinctive modern style. Wittop also performed as a dancer while in Paris.

In 1936, he traveled across the Atlantic Ocean on the S.S. Normandie to design costumes for the French Casino, a luxurious dinner theater in New York. While on board, he met the Australian-born mezzo-soprano Marjorie Lawrence; she was with the Metropolitan Opera at the time and commissioned numerous costumes from him, as did Carmen Miranda, and, later, Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba. The French Casino was short-lived due to the Depression, but Wittop designed for its shows in 1936 (with Erté) and 1937 before it closed.

Wittop then returned to Europe to dance, and soon was invited by Encarnación López Júlvez, who performed as Argentinita (the name a nod to La Argentina), to join her Spanish dance troupe. He left Paris before Germany invaded and toured the United States from 1940-42 to widespread praise under the name Federico Rey (Rey being the Spanish translation of Koning, both meaning “king”). He maintained a career as a costume designer, though, working for the Ice Capades in 1942 and 1943, the Latin Quarter (a New York nightclub), and the Broadway musical comedy Beat the Band (1942), for which Women’s Wear Daily described his contributions as “costumes of bewildering beauty.”

Just as he was becoming recognized as “one of the greatest of all costume designers,” Wittop enlisted in the U.S. Army. He suggested during his induction interview that he might fit well with an entertainment unit or, because he spoke French, Dutch, German, Spanish, English, and a little Italian, in the intelligence service, so he was surprised to be assigned immediately to a medical corps. He found creative outlets, though, performing for hospital patients and fellow soldiers, designing murals for the Officers’ Club at Fort Benning in Georgia, and in 1945 performing in OK—USA, an all-soldier revue in Germany directed by Mickey Rooney. He became a U.S. citizen in 1943, and was honorably discharged from the army in 1946.

Upon returning to civilian life, Wittop again pursued both dance and design. He formed his own dance troupe, Rhythms of Spain, then toured internationally as a duo with Pilar Gomez from the late 1940s into the mid-1950s. As he had done with Argentinita’s ensemble, he designed many of the costumes. Though the frequent travel made it difficult for Wittop to reestablish himself as a costume designer in New York, he did have some designing engagements during this period, resuming his work with traveling ice shows and the Latin Quarter and designing for a few Las Vegas productions.

HOLIDAY ON ICE, “OUR CRYSTAL ANNIVERSARY,” 19.8 x 24.9 centimeters, 1960. Freddy Wittop papers.

Ice skating shows originated before World War II, but became especially popular in the post-war decades as a major form of American family entertainment. Wittop designed first for the Ice Capades, then for Holiday on Ice from 1958-1970. While striving to bring Broadway glamour to the ice, he considered practical details, such as lining costumes with plastic where they might touch the ice so that the humidity would not ruin the materials, adding casters to support some of the more elaborate and heavy skirts, and including zippers down the full length of men’s pants so that they could change quickly without having to remove their skates. He recognized that details and subdued colors would be lost in these shows, which often played in huge venues like Madison Square Garden, and sought to design costumes with “bigness.” The price tags for the costumes were large as well; for example, for the Holiday on Ice of 1966, he spent $350,000 (about $2.8 million today).

Designing for the Latin Quarter was, in many ways, a continuation of his work designing for the Paris music halls, similarly featuring opulent costumes intended to entertain and titillate audiences. One columnist admired his outfits for the showgirls then questioned “how so little conceals so much in such an enticing manner.” For one of the later shows, Wittop explained, “They look like they’re wearing nothing at all, but the average costume costs about $750 or $800. They wear the best of everything. I’ve just returned from a buying trip to Paris for the Quarter. I bought 300 yards of gold lamé and lots of feathers and rhinestones.” In addition to designing for the Latin Quarter periodically in the 1940s, he designed for the shows from 1950 through 1963, making it a significant, if lighthearted, part of his career.

During one of the Latin Quarter performances, director Harold Churchman, actor Maurice Evans and producer Robert Joseph saw Wittop’s costumes and invited him to design for Heartbreak House, which opened in 1959 and marked the start of his prolific period of working with Broadway shows. It also signaled the conclusion of his time as a professional dancer, though he continued to take ballet classes to remain fit. His experience as a dancer informed his work as a designer—as his long-time partner Gil Duke, an interior designer, explained, “He knows how to make the costumes move.”

Click Image for Captions

FREDDY WITTOP SKETCHING, 24.1 x 20.3 centimeters, circa 1960. Photograph by Impact Photos Inc. (New York, New York). Freddy Wittop papers.

Following Heartbreak House, Wittop designed for Carnival! (1961), Subways Are for Sleeping (1961), and Hello, Dolly! (1963), for which he received the first of his six Tony nominations. Dolly went on to become one of the longest running shows on Broadway (it held the top spot for a while, and currently is number twenty), and his memorable designs were donned by many different Dollys besides Carol Channing, including Ginger Rogers, Martha Raye, Betty Grable, Pearl Baily, Phyllis Diller, and Ethel Merman. Wittop again pushed the fiscal limits, arranging for the original $20,000 allotted for costumes to be raised to about $90,000, and one press release noted, “He hates tiny budgets.” But, the investment paid off: he won the prestigious Tony Award and received rave reviews. Eleni, fashion editor for the Washington Star, described, “one kaleidoscopic scene,” as “breathtaking in its fashion impact,” adding, “cerise, purple, green, violet, yellow, orange, fawn, ecru, white, and bright blue, play against each other with great eye appeal.” Perhaps most significantly, the notoriously difficult producer David Merrick wrote to him on opening night, “Freddy, you are the most talented costume designer in the world.”

For Hello, Dolly!, as with many of his projects, Wittop began planning his costume designs by carefully reading the script in order to understand the characters that the costumes had to convey, and immersing himself in the study of the design of the era in which the production was set. He spent many hours at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and sometimes looked to paintings by Gauguin, Bruegel or Goya. He did not seek to create accurate period outfits, though. He wanted to capture the impression of the earlier times, while making the designs appeal to contemporary audiences and function as costumes. He also considered the lighting, the sets and how the costumes would work together as ensembles on stage.

Wittop always sought to purchase the finest materials available because the costumes had to not only look good, but they had to withstand repeated performances, harsh lights and active bodies. He also could be obsessive about finding the ideal materials, with one standout example being a feathered hat in I Do! I Do! (1966). While he had teased ostrich feathers into looking fancy for Dolly—he thought the character would appreciate the glamorization of inexpensive materials—he felt that Agnes, the character in I Do! I Do! played by Mary Martin, would only accept authentic Birds-of-Paradise plumes for her hat. However, it was illegal to import those at the time, so he searched far and wide for examples that came into the country before the protectionary laws existed, eventually finding the desired feathers in a storeroom on an old ice skating costume.

And, as Wittop had learned at the opera in Brussels, he had to work with the performers. He explained, “If the performers aren’t happy with what they’re wearing, they won’t give good performances, so I try to compromise in ways that agree with my sense of the style of the show and the performers’ need to feel comfortable.” For the musical Dear World (1969), he purchased an exquisite velvet robe by the House of Worth at a flea market in Paris for Angela Lansbury to wear as Countess Aurelia. Wittop later recounted that Lansbury found the long, hanging sleeves on the robe difficult to maneuver during rehearsals. So, instructed by the producers to make her happy, he handed her scissors and she cut off the sleeves, much to the producers’ subsequent dismay. He eventually restored the sleeves, and she wrote to him on opening night that she was ready to walk on the stage knowing that she looked “incredible and marvelous due to [his] talent and inspiration.”

COSTUME FOR HARRY BELAFONTE of gouache and watercolor on paper, 64.8 x 49.0 centimeters, 1961. Freddy Wittop papers.

Wittop designed for many other Broadway shows, including Bajour (1964), Kelly (1965), 3 Bags Full (1966), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1966), On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1965), A Happy Time (1968), George M! (1969), A Patriot for Me (1969) (with its much-hyped drag ball scene), and Lovely Ladies, Kind Gentlemen (1970). Of Bajour, Eugenia Sheppard, women’s editor for the New York Herald Tribune, gushed that the costumes gave her “chills and fever,” and that “at least a thousand yards of chiffon are swirling and frothing across the stage at one time in the maddest, most marvelous colors ever seen outside of a swatch book.” He also designed for projects beyond Broadway, including the play Judith in London starring Sean Connery (1961), Boris Godunov with the New York City Opera (1964), and Swan Lake for the American Ballet Theatre (1967). In what was likely his largest project, he designed more than a thousand costumes for To Broadway with Love, a salute to a century of Broadway musicals, for the Texas Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair, spending a headline-making $500,000 (more than $4.2 million today).

Not all of the projects Wittop worked with were successes. He stated of Kelly, which closed after its opening night, “beautiful clothes can’t save a bad show.” And he once lamented, “It is a shame that most of my best sketches were done for shows that flopped.” So, in 1971 Wittop retired, “disillusioned and disenchanted,” to Ibiza, an island off the coast of Spain in the Mediterranean.

In 1982, though, he came out of retirement and returned to New York to design for The Three Musketeers (1984), Wind in the Willows (1985), and Legends! (1986). Wittop and Duke relocated to Tequesta, Florida, and he spent time lecturing and teaching. The Henry M. Flagler Museum held a major retrospective of his work in 1988, and in the early 1990s he established a connection with the University of Georgia, where he became an adjunct professor in theater—often spicing up his classes with “a little flamenco dancing or a high kick or two.”

He was drawn to that campus after learning that it had acquired Max Weldy’s collection of more than 6,000 sketches for designs for the Paris music halls, including dozens by Wittop. Befriended by faculty and staff in the theater and the archives, Wittop placed his own papers—photo albums, sketchbooks, lecture notes, costume designs, and thirty-three carefully compiled scrapbooks—there as well, ensuring the preservation of the materials that document the impressive accomplishments of his celebrated career.

SUGGESTED READING

Mary Ellen Brooks, “Paris: Women in the Follies,” exhibition brochure, Athens, GA: Georgia Museum of Art, 1995, https://issuu.com/gmoa/docs/paris_women_in_the_follies.

Sylvia J. Hillyard and August W. Staub, “Freddy Wittop: Art Deco and the American Musical,” Theatre Design and Technology (Winter 1989), 17-22.

Angelo Luerii, Non Solo Erté, Not Only Erté, Costume Design for the Paris Music Hall, 1918-1940 (Vicenza: Guido Tamoni, 2005).

Roy Blakey’s Icestage Archive, https://www.icestagearchive.com.

Gary Chapman’s Jazz Age Club, http://www.jazzageclub.com.

ACTORS IN A PATRIOT FOR ME, 24.9 x 20.1 centimeters, 1969. Freddy Wittop papers.

You Might Also Like

Worn On

This Day

Ashley Callahan is an independent scholar and curator in Athens, Georgia, with a specialty in modern and contemporary American decorative arts. She loves spending time in the University of Georgia’s Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which is full of amazing collections such as Freddy Wittop’s archives, and friendly staff. She appreciates director Kat Stein’s suggestion to work with Wittop’s collection and Mary Linnemann’s assistance with photography. Callahan is currently working with another collection at the Hargrett as well, Frankie Welch’s textiles. She will curate an exhibition on Welch at the Hargrett in early 2022 and is writing a book on her and her career with the University of Georgia Press. You can read Callahan’s Ornament article on Welch in Volume 35, No. 1, 2011.