Harriete Estel Berman

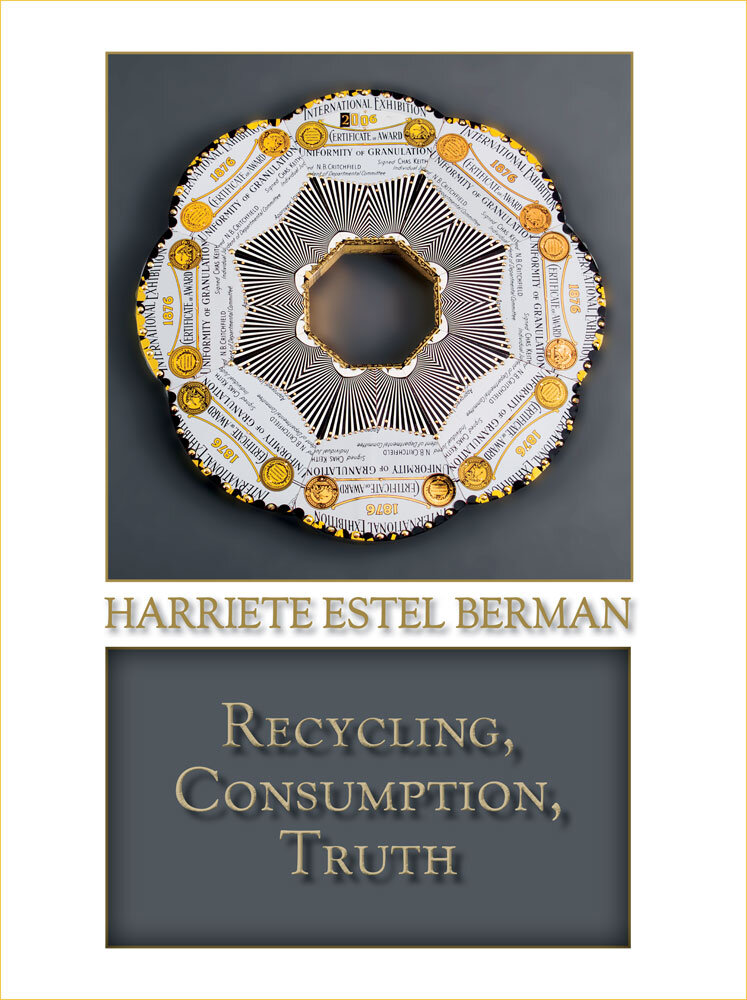

CALIFORNIA GOLD UNIFORMITY OF GRANULATION BRACELET of recycled post-consumer, litho-printed tin cans, ten karat gold rivets, brass detail, plastic core; fabricated, 1.5 centimeter depth x 27.0 centimeter diameter, 2006. Crocker Art Museum Collection. Photographs by Philip Cohen Photographic except where noted.

Fashioned from non-biodegradable refuse—bits of plastic salvaged from trash cans, dumpsters and city streets—the Recycle Collection jewelry of California artist Harriete Estel Berman elicits the wonder of resurrection: a return of relevance and even beauty to things woefully debased. Callow life rising from blasted fields, the delicate tendrils of pink, white, pale aqua, tangerine, and grass green belie the mundane matter composing them. Raised from an abject form of permanence and endowed with the grace and elegance proper to a higher order of immortality, the revivified materials dangle tantalizing implications of release from remorse for accumulated sin and the potential for serenity, sensory satisfaction and even optimism. But this optimism is achingly fragile; it is no coincidence that much of the Recycle Collection is the color of mourning jewelry.

Recycling can be a clever technique for an artist’s repertoire, and so an appropriate subject of aesthetic discourse, but Berman’s more considered intention is to situate her art squarely against the backdrop of contemporary consumerism and the race towards ecological catastrophe. Given the magnitude of impending consequences of anthropogenic climate change, if recycling is to achieve any real relevance it cannot remain simply a creative novelty or an ethical gesture on the part of a conscientious minority; it must become a structural practice in the daily life of nations, a practice as routine as sweeping the floor, brushing teeth, or, more to the point, taking out the trash. The fact that the reuse of refuse in art can still elicit wonder ought to be as disturbing as a floor show on the Titanic. Given its rags-to-riches sleight of hand and its exquisite anemone beauty, Berman’s Recycle Collection jewelry might be mistaken for just such a diversionary spectacle if it were not so clearly contextualized as a warning, albeit one wrapped, like a venomous predator, in gloss and color. Specifically, it is a warning against complacency. As such, the series is afflicted with the pathos inherent in every confrontation of crisis that may in the end prove to be no more than a forlorn hope.

Long an activist for a range of causes, Berman began incorporating recycled materials into her art in 1988 in order to make conspicuous use of otherwise worthless by-products of consumerism—initially, “tin” cans—and to draw attention to the myriad environmental problems that this wasteful lifestyle has perpetuated since the early twentieth century. Her first recycled works, bracelets crimped from flat shapes snipped out of discarded sheet-metal containers, cut to the heart of the problem by emphasizing a key factor that encourages excessive consumerism. Exploiting the barcodes printed on the salvaged metal containers, Berman highlighted what she described as a fundamental form of self-indulgence, a basic gratification underlying and motivating conspicuous consumption. Barcodes represent the vast array of commodities available to the contemporary consumer, whose choices reflect both financial means and implicit taste. In this respect they act as units of language, imprinting assertions of existence and value onto consumer products and, by association, asserting the existence and value of those who purchase them. Commodities are, in other words, the stuff of existential confirmation and procured self-esteem; the barcodes they bear are, Berman asserts, visual reminders of the way in which “we create identity for ourselves through the things we buy and the reasons we buy them.”

Although enamored of jewelry, Berman has explored various artistic means of diverting salvage from “the waste stream of society” toward a new productivity as commentary on sustainability. Much of her work with recycled packaging has been sculpture, like the recent Grass series that through its sinuously seductive but razor-sharp blades of recycled metal remarks on the conflicted nature of the American lawn: both a prized symbol of suburban success and a source of toxic fertilizer runoff and high-carbon lawnmower exhaust. Her wearable art has made even more explicit the connection between obsession over self-image and the shunting of environmental responsibility. Her Identity Bracelets, which have retained conspicuous evidence of their past as packaging, slyly feed the wearer’s vanity as unique and prestigious art jewelry while subtly diverting desire away from new materials toward those with a history of use, specifically use within a socioeconomic system that has made disposability as desirable as commodities themselves.

RECYCLE NECKLACE/BRACELETS of post-consumer recycled HDPE plastic, button catch, 2007-2009. Photograph by Liz Hickok.

HARRIETE ESTEL BERMAN. Photograph by Aryn Shelander.

The commercial strategy of planned obsolescence—which ensures, for example, that cell phones last an average of three years before their flimsy wiring fails—ought to inspire protest, but cultural conditioning has effectively deflected attention away from that absurdity. A major compensation for the ephemerality of products has been that their shoddiness implies permission to indulge more frequently in the new. If, as Berman stresses, buying has become a key method of identity formation, then reluctance to step back from consumerism, even in its untenable, hypertrophied form, is hardly surprising. Moreover, the idea of paying for the disposable sheath of advertising that envelopes the products we buy strikes us as not only reasonable but necessary. Packaging, both physical and figurative, has become the visible evidence of quality. Brand names, and not only those of luxury goods, are now essential, constitutive. Berman’s conflation of product and packaging—her creation of products from former packaging—accentuates the contemporary synonymity of the two: the inextricable relationship between the material and psychological sides of consumption.

BRACELET FROM IDENTITY COLLECTION (reverse) of post-consumer recycled tin cans, ten karat gold rivets on obverse, steel rivets on reverse, brass rivets on edge, 1.3 x 15.2 centimeters, 2007.

GOLD AND BLACK IDENTITY BEAD NECKLACE of recycled tin from post consumer recycled tin cans, brass tubing, polymer clay spacer beads, colored electrical wire cords, bead catch of recycled tin, Plexiglas, ten karat gold rivets, magnets, 3.0 centimeter diameter beads, 17.5 centimeter diameter necklace, 2006.

“BERMAID” SANTA ROSA BRACELETS AND DISPLAY: ROUND LUTHER BURBANK BRACELET of seed packet motif, sterling silver rivets, 16.5 height x 16.5 width x 0.8 depth centimeters. 5 SIDED SANTA ROSA PLUM BRACELET of embossed plum and leaves, sterling silver rivets, 13.2 x 13.7 x 5.1 centimeters. COLUMN BRACELET, SANTA ROSA STRAWBERRY LABEL WITH MULTI-COLORED STRIPES of “Peanuts” tin & mustard colored tin with red bow, overlapping tins with scalloped edges, brass rivets, Charles Schultz’s Peanuts character Chex mix party, 9.2 x 9.5 x 5.6 centimeters. WOODEN CRATE CUSTOM DISPLAY of three dimensional fruit crate label constructed from recycled tin cans, aluminum rivets, paint, ten karat gold rivets, wooden crate, 25.4 x 40.6 x 24.1 centimeters, 2009-2010.

Berman’s conversion of packaging into product in the Identity Bracelets series—given the branding information printed on the salvaged sheet metal and its links to the self-image of the consumer—was always tacitly an issue of display. Adding another layer to the conceptual strata of her work in a series titled Fruit Crates she has made display a primary focus by enclosing her recycled-packaging bracelets themselves in packaging. These works—which, as the series title implies, consist partly of wooden containers—function as frames or pedestals for Identity Bracelets. At the same time, their presence is competitive, rivaling that of the objects they display. The result is a larger, multipartite form of work clearly oriented toward the detached, hermetic space of exhibitions rather than the promenades of Vanity Fair where prestigious art jewelry is most at home. The shift in orientation corresponded with a change in Berman’s perspective on the nature of her work. “I’ve made many pieces about buying more,” she says, “which was one of the reasons that I felt I needed to just make pieces for exhibitions. I’d like people to buy them, but I decided that I’m not going to make more stuff just so that people are able to buy more stuff.”

A prime example of a Fruit Crate sculpture, into which are nestled three crimped-metal Identity Bracelets, is titled Bermaid: a pseudo brand name and feminist pun that simultaneously banishes masculinity from the artist’s last name and emphasizes product production. Inscribed on a label celebrating the tradition of color lithography on California fruit crates of the twentieth century, the word floats above a succulent bounty of ripe strawberries, California Spanish architecture, and green fields receding over the horizon. “The Graphics are so wonderful on the old fruit-crate labels,” Berman observes, “and the lithography business itself was in San Francisco, so the Fruit Crates became about California. And don’t forget that California is a leader in the recycling movement to this day.” Having moved to California in 1980, Berman was herself something of a recycling pioneer. “I lived in Palo Alto when there was no such thing,” she explains. “There was no municipal place for it, so I used to have to take my recycling over to Stanford University. You had to put some effort into it back then.”

Today in her art that effort is directed toward recycling as repurposing, a process that can be far more time consuming—though the tour de force of her Recycle Collection impresses as much for the sheer accumulation of discarded plastic as for the investment of time and labor that it represents. That ambitious piece, resembling a feather boa as spikey and sinister as an evil stepmother’s stole, measures twenty-six feet in length. “With big work like that you typically only get a few chances to show it,” Berman notes. “Suzanne Ramljak had invited me to be in an exhibition called Uneasy Beauty. I showed her some photos of black-plastic bracelets and said, ‘I’ve always wanted to make something big.”

While the Recycle Collection has exploited the varied palette of attractive color offered by plastic refuse, Berman has focused most consistently on black. Shredded primarily from to-go salad bowls and rotisserie-chicken trays, the black plastic strikes Berman as most relevant to the content of her work, and not simply because of its somber associations. In the industrial context, she explains, black plastic “isn’t recyclable at all.” Most plastic discards are sorted by NIR (near-infra-red) optical scanners that have difficulty recognizing black. “So, really and truly,” Berman asserts, “black is the evilest of all plastic.” Her extravagantly long boa—a reminder of the volume of the black-plastic detritus of consumerism filling the waste dumps of the world—is in this respect like Jacob Marley’s chain, a ponderous burden of sin forged one black-plastic coffee-cup lid at a time.

In part, problems like the daunting accumulation of black-plastic waste—and, of course, the larger and more dire issue of anthropogenic climate change—can be attributed to lack of awareness, to which the most effective remedy is truth. The word presented itself to Berman as appropriate for a label on a Fruit Crate some time in 2015, but the resulting sculpture would languish in the studio partly finished for two years before a clear idea emerged of what might occupy it. The Truth Fruit Crate would become akin to a sarcophagus in 2017, shortly after the notoriously underwhelming crowd at the Trump inauguration provoked the first in a long string of blatant contradictions of truth. “Up until then we all thought truth was absolute,” Berman remarks, “a 100% guarantee. Then Trump came in, and suddenly there was talk of alternative facts. It astonished us at the time; we were in shock—but it just continued, and now we’re accustomed to it.”

The panoply for the post-truth era that occupies the Truth Fruit Crate consists of three bracelets: Web of Lies, Alternative Facts and Circular Logic. The first, ostentatious to the point of unwieldiness, appears cut from sheets of solid gold but is in fact composed of cheap metal plated for a grandiose effect. The second spells out the absurdity “alternative facts” in letters that bear nutrition information retained from the source objects. “I was thinking of the deceptiveness on labels and how they tweak our perceptions of food as healthy,” Berman explains. “No-cholesterol pasta, for example. Pasta never had cholesterol in the first place.” The last bracelet of the triad, Circular Logic, is appropriately the most convoluted, consisting of a band of sheet metal some forty inches long from which the title has been cut repeatedly. Wrapped back on itself to the point of near illegibility, it is voluble but meaningless. “It’s one of my recent favorites,” Berman says, “since it resonates with so much of what has gone on in contemporary politics.”

BLACK PLASTIC GYRE NECKLACE BOA of monofilament, post-consumer black plastic waste from take-out containers, serving bowls, roast chicken trays, bottle caps, pen caps, black plastic straws, and other items. The ends of the necklace may look like a “jewelry catch” but they are actually black plastic spools from CDs. Plastic is cut by hand, drilled, and threaded; 22.9 x 35.6 centimeters x 7.9 meters, 2018.

“FABRICATING TRUTH” BRACELETS AND DISPLAY: WEB OF LIES BRACELET of gold-plated brass, 14.1 x 14.6 x 0.6 centimeters. ALTERNATIVE FACTS BRACELET of recycled tin cans printed with Nutrition Facts, 5.1 x 14.0 x 14.0 centimeters. WOODEN CRATE CUSTOM DISPLAY of fruit crate label constructed from recycled tin cans, gold rivets, Plexiglas, wooden crate, 14.0 x 35.6 x 36.8 centimeters. CIRCULAR LOGIC BRACELET of recycled tin can from Lost TV Series game. The bracelet says “Circular Logic” looped three times; 7.6 x 17.8 x 16.5 centimeters, 2014-2017.

The Fabricating Truth bracelets court excess, but to describe them as parodies seems overly optimistic in an age that has witnessed mass delusion. Parody requires a reference point in reality. It dies when a common acceptance of fact gives way to the opinion that facts are replaceable if inconvenient to a favored narrative. Nor is there any space for satire when its intended target has monopolized the grotesque and reveled in vulgarity. At such a point, satire falls flat, and all attempts at parody end as genre: not send-ups of the ludicrous, the corrupt, the incompetent, the hypocritical, and the crass but only iterations of the moment that neither spark humor nor induce shock. If years from now Berman’s works should prove to have been more documentation than goads to action, it would be no more than the pessimism of the moment portends. Nevertheless, her gesture is worth making, if only as a message to posterity that truth was not lost entirely among the generations that cost it the earth.

SUGGESTED READING

Estrada, Nicholas. New Rings: 500+ Designs from Around the World. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Hemachandra, Ray and Chunghi Choo. Showcase: 500 Art Necklaces. New York: Sterling Publishing, 2013.

Fenn, Mark. Tales from the Tool Box: Narrative Jewelry. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2017.

Markle, Jamie. Acrylic Works 4: Captivating Color. Cincinnati: North Light Books, 2017.

You Might Also Like

TINKER, TAILOR, SHOEMAKER

Glen R. Brown is Professor of Art History at Kansas State University, and the author of the 2021 book Jun Kaneko: The Space Between. Brown has been a longtime contributor for Ornament, having written his first article on Texan jeweler Allison Black in Volume 21, No. 2, 1997. He finds reassurance in the work of Harriete Estel Berman, a pioneer in the use of recycling in jewelry and an outspoken advocate of truth. “At a time when the threat of climate change dwarfs that of our current pandemic,” he says, “it’s inspiring to see an artist working so resolutely to dispel the fog of deception about the dangers facing us. Work like Berman’s makes writing about art feel less like fiddling among the flames.”