Joyce J. Scott Volume 45.1

WE TWO (necklace) by Joyce J. Scott and Art Smith, of bronze, seed beads, c. 1970s. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gallery Instructor 50th Anniversary Fund in support of the Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection and funds donated by Stephen Borkowski. © Joyce J. Scott.

When Joyce Scott was featured in Ornament’s 15th Anniversary issue in 1992, she called herself a “Migrant Worker for the Arts”. She was known primarily for beaded jewelry, small sculptures and performances, always highlighting social issues of particular concern to African Americans. Today at age seventy-five, her mission has broadened and deepened as she continues to project a persistent, uncompromising voice against social injustices and atrocities throughout the world. “I want my art to induce people to stop raping, torturing and shooting each other,” she says. Scott’s artistic expression has evolved to include forty-inch-wide beaded tapestry “stories,” torso-covering necklaces, sculptures ranging from tiny hand-held objects to larger-than-life figures, and impressive indoor and outdoor installations.

Concept, story and process all tumble out together as Scott is forming a piece. Her works in all sizes are layered with graphic imagery and studded with dimensional figures and inclusions. Her jewelry employs the sheer beauty of glass beads, rich color, exquisite craftsmanship, and ironic humor to entice viewers to look closely for the message or story in the piece. They discover disturbing themes of murder, rape, war, and other human foibles that are meant to spark serious conversations. “My best work is about issues that bug me,” says Scott. “The wearer has to have the cojones to wear it—she’s in it with me!”

Themes that feed Scott’s work come from observing human behavior at home, and wherever she travels. She has observed the tendency to stratify and discriminate in all cultures. While traveling in the Sudan she learned that discrimination against albino children is so extreme that it results in their murder and dismemberment, and has made several sculptures about this issue. Sexual violence, gun violence, racism, sexism, sex trafficking, women’s vulnerability, body image, “all the stuff we’re not supposed to talk about but we know exists” are fair game for Scott. The Sneak necklace depicts a murderer peering over the wearer’s shoulder as he stalks his victim.

Not all of Scott’s work is didactic. She produces occasional meditative jewelry, usually monochromatic, savoring the sheer beauty and luminescence of the glass beads. Some quirky sculptures come together intuitively or are “happy accidents.” A broken beaded teapot form became, through some ingenious repairs and 3D additions, an amusing Teapot Lady sculpture.

Claiming to have been an artist since she was in utero, art truly has been Scott’s lifelong pursuit. She learned to sew with beads from her mother, her first art teacher. She pursued a degree in art education at Maryland College of Art and earned a scholarship to Instituto Allende in Mexico, where she received her MFA. That experience ignited an interest in travel that has taken her virtually around the globe in search of inspiration. Joyce’s Necklace, incorporating beads and collected charms from her early travels, was a work in process over a seven year period, and chronicles those voyages in a single beaded portrait.

DEAD ALBINO BOY FOR SALE, 2021-2022. Courtesy of Goya Contemporary. Photograph by Mitro Hood. THE SNEAK NECKPIECE of seed beads, 1989. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Helen Williams Drutt Collection. © Joyce J. Scott. Model: Mia Vaughnes. Photograph by Robert K. Liu.

At the beginning of her career, Scott’s artistic focus was on quilts and weaving as an artist and teacher. Nuclear Nanny is an early 1980s quilt made when threats of nuclear war were prevalent. Its reverse appliqué technique was inspired by time spent in Panama with Cuña women learning about their mola work. Three Generation Quilt contains patchwork elements made by Scott, her mother, and her grandfather.

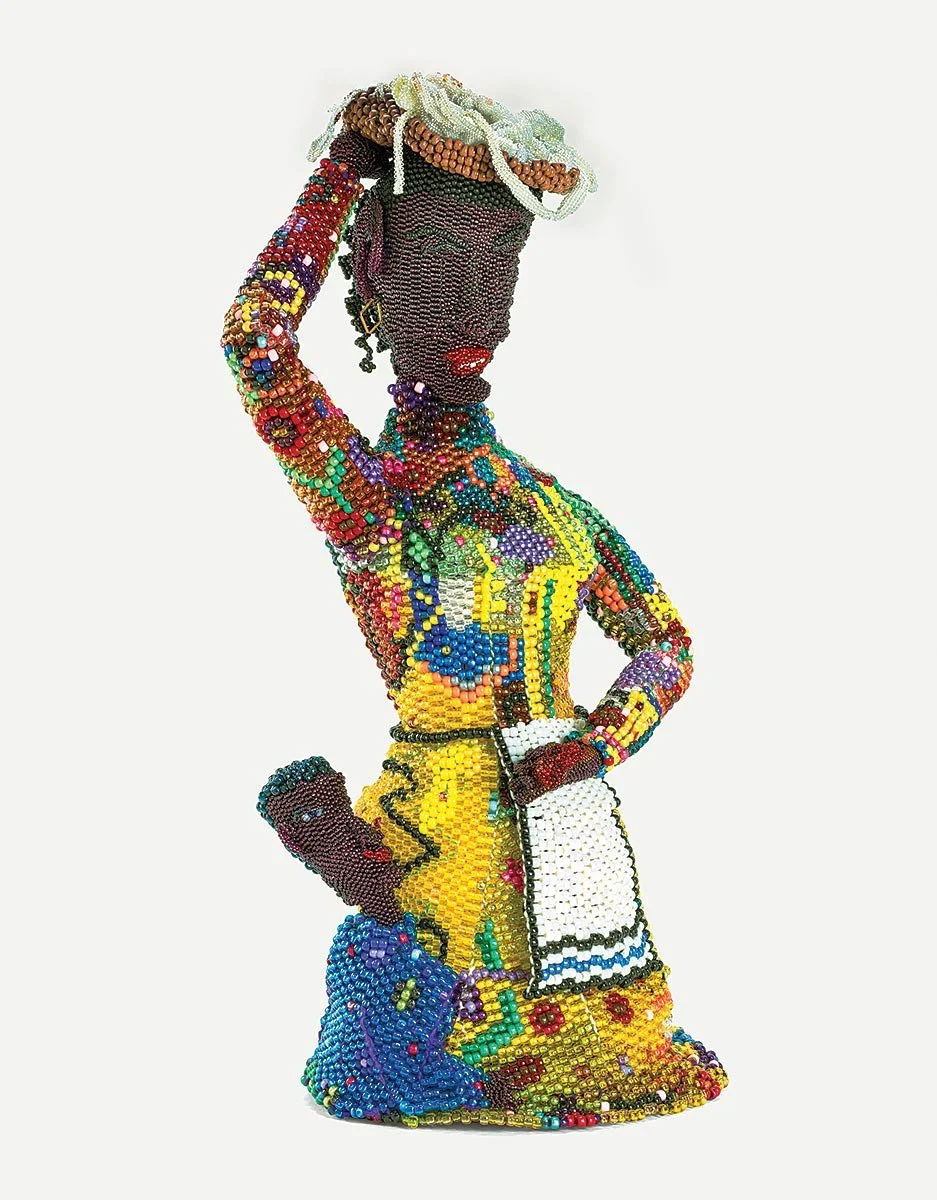

In 1976, Scott learned the peyote stitch for beadwork from a Native American woman while she attended Haystack Mountain School of Craft. This single technique changed Scott’s life and the direction of her art. Quirky beaded sculptures and jewelry quickly emerged. Not content with using only beads, Scott will incorporate just about any found object into an artwork. Her “Mammie Wada” figure is decorated with discarded crab claws that she collected from a Baltimore restaurant kitchen, brass buttons and synthetic hair. It is one of an ongoing series of “Mammy” sculptures inspired by her mother that refer to the lives of childcare workers who must care for others’ children in order to care for their own.

Scott constantly seeks out new techniques to deepen the scope and content of her artwork. Residencies at the glasswork studios of Penland, Haystack and Pilchuk provided more turning points. She learned to collaborate with glass blowers, lamp workers and cast glass artisans to create larger glass sculptures which she could later adorn with beads.

MAMMIE WADA of mixed media, beads, thread, raffia, yarn, hair, ceramics, and shells, 1981. Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of J.B. Hanson and Tom Haulk, Baltimore. © Joyce Scott. Courtesy of Goya Contemporary. Photograph by Mitro Hood.

Click for Captions

HEART HEAD NECKPIECE of glass beads thread, wire, beaded bead and loop clasp; peyote stitch, 39.4 x 25.4 x 1.3 centimeters, 2023. Collection of Crocker Art Museum. Model: Aisha Butler. Photograph by Jeff Butler.

Scott was also fortunate to spend three residencies at the famed glassworks in Murano, Italy, between 2011 and 2019. In describing the Murano experience, she said, “It was a stretch for all of us. Since I don’t speak Italian, I worked on beads and sang opera and made drawings on the floor (for the artisans) while they blew glass–I found ways to communicate.” The Murano collaborations have yielded increasingly large and complex glass sculptures such as “Aloft,” a two-headed mother and child figure of hand blown Murano glass. Back at home, Scott completed the sculpture with beadwork for arms and the child’s body, then crafted a mosaic base.

One goal Scott really wanted to achieve in her collaborations with glass workers was the fusing of beadwork and glass together. Attempts to do so in early residencies failed. Finally,on her second Murano trip, she discovered the secret was to use antique beads that are chemically similar to the historic Italian glass formulas. Beaded faces fused onto the glass as it is blown yielded a completely new effect.

“I’m working against the norm—creating a new standard,” Scott says. “Fusing beads opened a new door—no one has done this before! I’m the right person for this job!”

When asked how her jewelry has developed in tandem with the sculptures over the years, Scott replied, “When I was very young, I tried everything, integrating materials and techniques. Broad strokes. Very joyous, however I wasn’t truly becoming one with the techniques. In doing so I learned skills I could repeat, summon at will. This allows me to improvise with a fluidity that comes from Knowing. My jewelry evolved as a well-honed addition. It allows me to converse with a variety of forms, mediums and content/context. Also inviting the wearer to join in my concept.”

Harriet Tubman is a powerful inspiration for Scott. A forty-inch-long beaded tapestry Scott made during Covid depicts Tubman’s life. ”She is a great light for me about what you can be,” Scott says. An escaped slave, Tubman became a “conductor” for the underground railroad, leading many enslaved people to freedom on a route from Maryland to Canada before the Civil War. Tubman also served the Union Army as a nurse and a spy during the Civil War. Later, she supported the women’s suffrage movement.

Scott created three Harriets for her massive 2019 installation at Grounds for Sculpture in Trenton, New Jersey, Harriet Tubman and Other Truths. A ten foot tall glass Harriet, inlaid with beads and sporting a glass rifle, guarded the entrance. Behind her, a life-sized beaded female hung, lynched, from a tall tree. Quilts directed visitors to the various parts of the exhibition just as quilts had served as signposts indicating ‘safe houses’ along the ‘railway’ route. In a more intimate section of the installation, the beaded sculpture, Harriet Tubman as Buddha, presided, holding a rosary made by Scott’s mother, who, she believes, shared Tubman’s qualities of bravery, perseverance and wisdom. At the finale, Scott had modeled a fifteen foot high Harriet figure out of soil and dressed her in beads. This figure eroded slowly away during the exhibition period “just as Tubman’s story slowly eroded from our memories,” says Scott.

Scott works daily (and often nights) in her Baltimore studio, the next-door twin to the row house she has lived in for over forty years. Scott traces her lineage back through laborers, sharecroppers and slaves in North and South Carolina, and takes great pride in her heritage. Her mother and grandparents on both sides of her family were craftspeople and quiltmakers, and their surviving quilts are some of Scott’s most prized possessions. Her late mother, Elizabeth Talford Scott, is noted for improvisational quilts that expanded the possibilities of quilting beyond tradition and is a revered figure in the history of quilting in America. “My ancestors were always making a way through ‘no way,’ always with humor,” Scott says. This is certainly an attitude that Scott shares and expresses through her art and her ‘never give up’ approach to life.

Click For Captions

The Baltimore Museum of Art has honored Scott with retrospective exhibitions twice in her lifetime. Her first retrospective, “Kickin’ It With the Old Masters” from 1999, presented twenty-five years of her artistic accomplishments. Her current, comprehensive, fifty-year retrospective at the museum titled “Walk A Mile In My Dreams” just ended its Baltimore run. It travels to the Seattle Art Museum to be on view from October 17, 2024 through January 19, 2025. The massive exhibition displays one hundred thirty works, including several installations. Scott could occasionally be found ‘in residence’ during the exhibit, greeting visitors while ensconced in her Seat of Knowledge installation, surrounded by her family’s quilts and draped in a prayer shawl made by her mother.

The curators of “Walk A Mile In My Dreams” are Cecilia Wichmann and Catharina Manchanda, and they have a lot to say about Baltimore’s champion artist. “From the beginning of her five-decade long career, Joyce J. Scott has recognized that adorning the body sets the stage for an encounter. She makes art that coaxes us to let our guards down and connect in conversation by acknowledging our differences,” Wichmann and Manchanda explain. “Over the last twenty-five years, this idea has continued to permeate her work in wearable and free-standing sculpture, performance and installation with formidable ingenuity and superlative craft. Scott’s innovation in embedding glass beads into the glass blowing process and the increased scale and ambition of her works are demonstrated through figurative sculptures like Aloft, which incorporates intricate beadwork that serves as both regalia and connective tissue, a conceptual throughline entwining blown-glass mother and child.”

Continuing to trace that throughline, they touch upon the evolutionary DNA that winds its way into all of her creations. “Her sculptural necklaces—such as the monochromatic Passion and ladder-like Yield—signal the artist’s relentless pursuit of ever-more layered compositions, color harmonies and perspectival shifts. In the past decade, Scott has also developed extraordinary ‘graphic novels or fairy tales’ that adorn the wall as beaded tapestries, closely related to her necklaces (though too large to wear) and to her early fiber work and story quilt tradition passed down within her family,” they continue. “The retrospective installation The Threads That Unite My Seat of Knowledge has led Scott to consider other forms of architectural adornments and the particular effects of light in work such as the tapestries. Ultimately, Scott’s work has evolved non-linearly through learning, often in community with others, the constant revisiting of all modalities, and the skill and experience gained from each new venture that propels her forward.

Concurrently, “Messages,” a traveling exhibition featuring jewelry and small sculptures organized by Mobilia Gallery, honors the long association they share with Scott. An exhibit of Scott’s recent prints is on view at Goya Contemporary in Baltimore.

The prolific fiber artist/sculptor/jeweler/printmaker/writer/singer/actor/comedienne/teacher/lecturer was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2016, the Smithsonian Visionary Award in 2019, and has received four Honorary Doctorate degrees among many, many other honors so far. Although Scott’s knees may have slowed the performance side of her life a bit, she is still actively lecturing, creating and presenting musical performances in the music duo Ebony and Ivory, writing for the stage, and coaching young performers in improvisation. Mentoring young visual artists of color is another item Scott is able to fit into her packed schedule “because having knowledge makes you want to share it.” When she advises someone with artistic aspirations, she tells them what her mother used to tell her: “If you believe something is there for you, go get it!”

Recently, Scott began adding mosaic bases to some of her sculptures and is excited about incorporating mosaic elements into her jewelry. Future work will likely include a mix of mosaic and beads and “astounding” jewelry made by “pulling the truth out of the materials.” She is also considering writing an updated version of her book, Fearless Beadwork, “If I am able to stay still enough to write it.”

Scott is most proud of never giving up or settling in her lifetime. “I am blessed in wonderment every day of my life. At seventy-five I’m still going after it! I am always pushing myself to go beyond my personal expectations, as my parents did. Why else am I here?”

“Joyce J. Scott: Walk A Mile In My Dreams ” travels on to the Seattle Art Museum, from October 17, 2024 through January 19, 2025, 1300 1st Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98101. Scott can be reached through Goya Contemporary, Mill Centre, 3000 Chestnut Avenue #214, Baltimore, Maryland 21211. You can visit their website at www.goyacontemporary.com.

SUGGESTED READING

Benesh, Carolyn L.E. 1986 “Message Through the Veil: Joyce Scott’s Beaded Jewelry.” Ornament 10(2): 32-33, 78.

Searle, Karen. 1992 “Migrant Worker for the Arts. Joyce Scott.” Ornament 15(4): 46-51, 75.

Benesh-Liu, Patrick R. 2015 “Maryland to Murano. Neckpieces and Sculptures by Joyce J. Scott.” Ornament 38(1): 50-53.

Mobilia Gallery (eds.) Joyce J. Scott: Messages. Stuttgart, Germany: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2023.

Green-Rifkin, Coby (ed.) Joyce J. Scott: Harriet Tubman and Other Truths. Hamilton, NJ: Grounds For Sculpture, 2018.

INSTALLATION PHOTOGRAPHS. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

MOBILIA GALLERY: MESSAGES

HE SAID WHAT? NECKPIECE of glass beads, thread, velcro, leather, peyote stitch, 61.0 x 38.1 x 0.3 centimeters, 2022. Collection of Edward Smith. Model: Aisha Butler. Photograph by Jeff Butler.

We have had the pleasure of exhibiting the work of Joyce J. Scott for over forty years. Her work continues to amaze and delight us. She has finessed her craft by reinventing the peyote stitch, allowing her to create necklaces that are pure sculpture with figures seemingly suspended in air, gracefully surrounding the neck of the wearer. Story Stole (2021) and Yield (2023) are examples, both incorporating lamp worked glass elements and a variety of glass beads in various sizes. Hues (2023), the most recent example of Scott’s sculptural necklaces, depicts several figures sitting, sprawling and standing around the wearer in a spectrum of blues.

In 2012 Scott made the first large flat necklace, Bib Necklace. When worn, it covers most of the torso and is reminiscent of a beaded wall tapestry. This was followed by another large necklace, Fairytale in 2019 and, most recently in 2022, He Said What?, which thrusts us into a conversation, most likely one filled with gossip, between Scott’s signature figures.

Another recent large scale neckpiece inspired by one of the most popular war protest songs of all time, War What is it Good For, Absolutely Nothin’, Say it Again brings another dimension to Scott’s necklaces with multiple layers of beadwork and meanings. The piece is reversible and both surfaces are alive, crawling with images of war and violence, bringing the battlefield to us.

Coming full circle: Scott continues to revolutionize and transform the potential of beadwork, waking up the world with her sly humor and in-your-face social commentary. A recent work and commission for the Dallas Museum of Art, Dickwhip (2022) is a perfect example. Scott made the neckpiece in response to an image she saw of Haitian refugees at the Texas border being chased and whipped with horse reins by Border Patrol officers on horseback in 2022. Dickwhip is constructed using glass beads, fire line (metal thread), and fabric stuffing.

Modeled after a whip, the neckpiece spans sixty-four inches long with a penis as the whip handle and words describing the event fanning from the whip’s end. It is worn by wrapping the length of the whip around one’s neck.

Joyce J. Scott continues pushing the boundaries of her work to new horizons. Her passion for the art, relentless pursuit of perfection and commitment to social reform through her work has made her an icon of the contemporary art world.

Karen Searle is a fiber artist, journalist and teacher. She was a frequent contributor to Ornament during the ’90s, and has enjoyed revisiting her 1992 profile of Joyce Scott for this issue. She is the former editor/publisher of Dos Tejedoras books on cultural traditions in textiles and also published The Weavers Journal. Writing artist profiles for Ornament inspired her to pursue an MFA degree as an older adult in order to develop her sculptural fiber work. She can be found creating in her St. Paul, Minneosta art studio or teaching at the Textile Center of Minnesota or the Weavers Guild of Minnesota. Her most recent book is Knitting Art, containing profiles of United States and Canadian artists whose medium is knitting.