Timo Krapf Volume 45.2

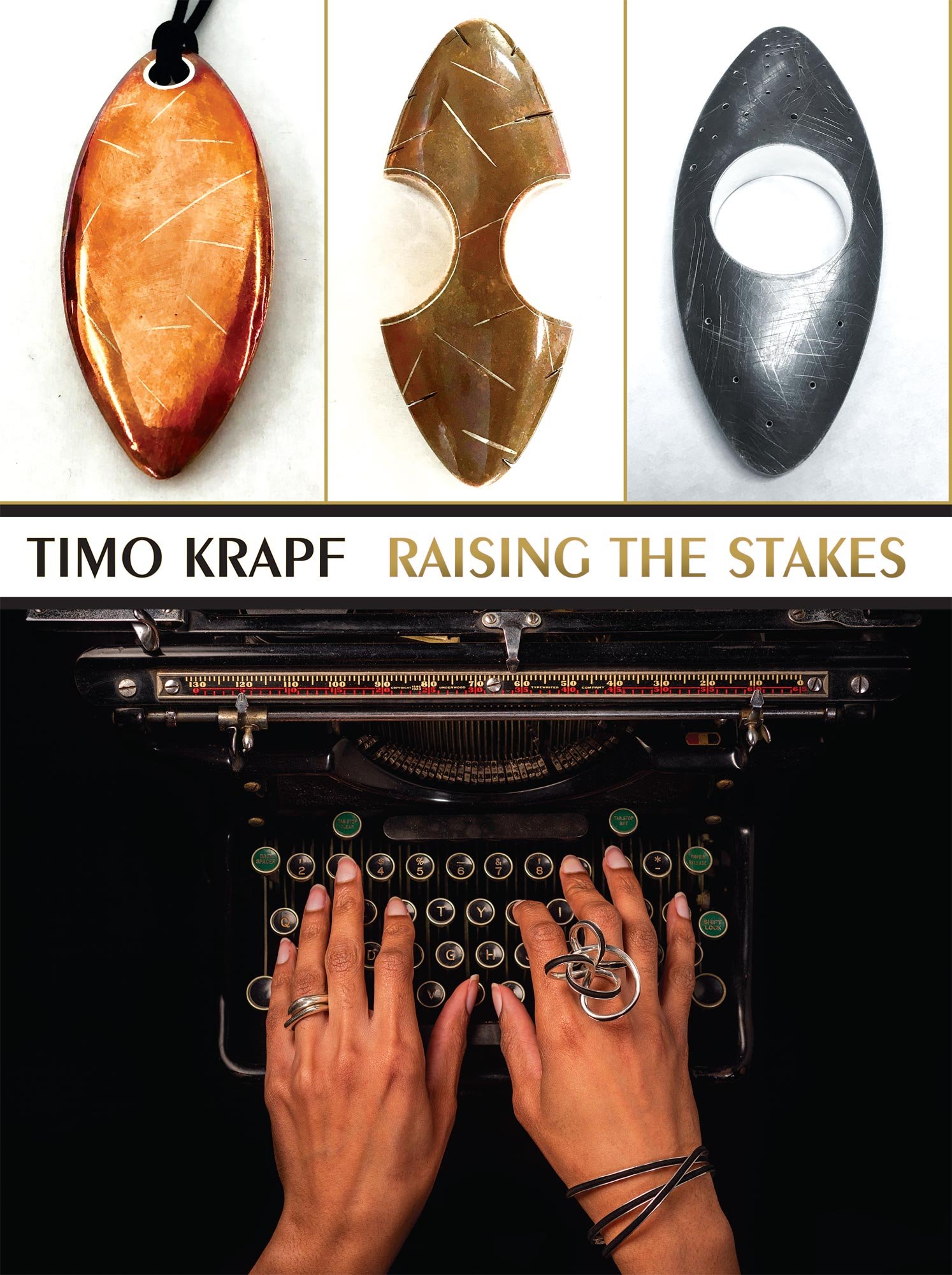

PENDANT of copper and sterling silver; hydraulic press, 6.5 x 2.8 centimeters, 2017. FINGER RING of copper and sterling silver; hydraulic press, 6.5 x 2.8 centimeters, 2017. RING of sterling silver; hydraulic press, 6.5 x 2.8 centimeters, 2017. Photographs by Timo Krapf. MODEL TYPING, WITH JEWELRY: Stack of 3 Anticlastic Bands of sterling silver, 2.4 x 0.5 centimeters, 2018; Cosmos Ring of sterling silver and leather cord, 5.0 x 4.0 centimeters, 2019; Anticlastic Wrap Cuff of sterling silver, leather, 4.0 x 5.5 centimeters, 2019. Model: Marina Boswell. Photograph by Walter Colley Images.

CHAIN MAIL SHIRT, 53.0 x 56.0 centimeters, 2014. Model: Timo Krapf. Photograph by Walter Colley Images.

The ancient metalworking technique known as anticlastic raising has roots that date back to the Bronze Age, as early as 3000 B.C., when Celtic metalsmiths made ribbon torc (or torque) necklaces by hammering strips of metal over a curved object such as an antler. Its reemergence in the contemporary jewelry world can be traced to the 1970s, and especially to the work of two influential pioneers: the Finnish-born metalsmith Heikki Seppä, who taught at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan and at Washington University in St. Louis; and the American jewelry artist and sculptor Michael Good. In 1977, Good took a workshop with Seppä in anticlastic raising and brought the technique back to his studio in Rockport, Maine, where he began experimenting with jewelry forms.

Seppä and Good have mentored subsequent generations of metalworkers, including Juha Koskela of Finland; Betty Helen Longhi of North Carolina; Cynthia Eid of Massachusetts; and the sculptor Benjamin Storch of Melbourne, Australia. An emerging talent firmly rooted in this tradition is Rochester born jewelry artist Timo Krapf.

In fact, it was in the studio of Michael Good, a family friend, that he first encountered the technique. “My introduction to anticlastic raising was when I was nine,” says Krapf. “We took a family trip to Maine to visit Michael and his late wife, Karen. I was fascinated by his workshop and asked if he would show me how his pieces were made. I ended up spending two days at his studio and learned to make my first anticlastic shapes: a hyperbolic paraboloid and an open-seam spiculum. At the end of our stay, Michael sent me home with a few tools, but I didn’t put them to much use until I graduated high school and started studying jewelry.”

PETAL EARRINGS of sterling silver, 1.0 x 5.0 centimeters, 2016. Photograph by Timo Krapf.

Krapf had grown up in the orbit of the jewelry world. His mother, Barbara Heinrich, is a distinguished jewelry artist who has served as president of the American Design Jewelry Council, and whose eponymous Rochester-based studio has an international reputation in the field. At a very young age, Krapf recalls making a silver band with the help of a cousin from Germany who was visiting to do an apprenticeship in jewelry. More idiosyncratically, as a high school student he ordered 400 meters of steel wire and made himself a chainmail shirt. “Honestly, I have no idea why I did it. I was always fascinated by knights and swords and armor.... It did make me realize that I enjoy working with my hands and should consider going into jewelry.”

After graduating high school, he enrolled in the jewelry arts program at George Brown College in Toronto. “It’s a college, not a university, and in Canada, they make a big distinction between the two,” says Krapf. “I was one of the very few people that was right out of high school. Most were in their mid-20s, some in their early 30s, and some in their 40s or 50s.” The three-year program at George Brown offers a very hands-on education, with a focus on practical skills. “I had two semesters of metal finishing, where all we did was polish and learn how to clean things up properly,” he recalls. “My third year was when we got to go more into our creative side and design things, build a body of work.”

During the summers he returned to Michael Good’s studio in Maine, where he helped the artist with jewelry and sculptures while continuing to explore the anticlastic technique he had first encountered during his childhood visit. “Working with Michael was wonderful. I was also living with him while I was there, and we became close friends,” says Krapf. “It wasn’t any sort of like formal apprenticeship. It was more just being at a studio and learning from him.”

CUFF of eighteen karat gold and black diamond; anticlastic raising, 5.5 x 7.0 centimeters, 2017. Photograph by Mark Nantz.

Krapf was drawn to anticlastic raising for its ability to create hollow forms with flowing, organic curves that are light but also durable. “There are two types of metal forming: synclastic raising and anticlastic raising,” he explains. “Synclastic raising is traditional metal forming where all the planes are moving in the same direction. So that’s a bowl or a spoon, anything like that. With anticlastic raising, you’re creating a compound curve. So one curve is bending opposite and perpendicular to the other. So if you were to take a square piece of metal, and take two corners and bend them down and two corners and bend them up kind of like a saddle shape—or in math, it would be a hyperbolic paraboloid—that’s an anticlastic form.

“Now, if you do that with a long strip of metal instead of just the square, you get what’s called an open-seam spiculum. A spiculum is a tapered tube. The traditional way to make a form like that, you would first make a tube, and then you would have to solder the whole edge of the tube—and then, often, put some sort of like wax or resin inside to give it structure, because if you were just to try to bend it, you would create a big kink in the metal. … Whereas with anticlastic raising, as you’re forming it, you can get much tighter spirals and it’s just a different way of doing it.”

After completing the certificate program at George Brown in 2017, Krapf returned to Rochester to pursue a BFA in metals and jewelry design at Rochester Institute of Technology. Here, he began applying and refining the skills he had acquired, extending his designs to create a distinctive body of work.

Among these early designs was an “Orbit Pendant” in platinum, a material less commonly used in anticlastic raising due to the difficulty of working it. The spiraling pendant is suspended from a thin black leather cord that coils around the contours of the metal, following its sinuous curves. A 14 millimeter silver-gray south sea pearl hangs suspended at the bottom, like an enormous raindrop about to burst. The elegant incorporation of the latter element garnered this piece the 2018 Orient Award in the International Pearl Design Competition. The following year, while a senior at Rochester, his “Open Spiculum Cuff with Black Diamond” received the Saul Bell Design Award for an Emerging Jewelry Artist 22 Years of Age or Younger.

ORBIT PENDANT of platinum, 14 millimeter South Sea pearl and leather, 2.0 x 4.1 centimeters. Photograph by Mark Nantz.

Upon graduating from RIT in 2019, Krapf spent six months in Canada working as a canoe guide, something he has done numerous times over the years. When he returned to Rochester, he immediately went back to jewelrymaking, working two days a week at the Barbara Heinrich Studio and spending the rest of the time on his own pieces. “I was still developing my lines, and we were doing all the shows together, my mom and I,” he says. “And then Covid hit.”

While there would be no in-person shows for several years, Krapf recalls that “in some ways, it was a nice period of time where the studio was completely empty and quiet.”

His work continued to expand and develop, including a prolific series of “Wave Link” cuffs, necklaces and rings that feature undulating metallic forms whose seams open to reveal rows of black diamonds embedded like seeds within. Another series of “Dual Tone” pieces play on the contrasts between different metals and finishes, juxtaposing twinned and sometimes intertwined forms in gold and silver.

“One advantage of anticlastic jewelry is that it allows me to work in much thinner metal than other jewelry techniques such as casting. This is particularly beneficial in earrings where weight is an important factor in comfort. I can make pieces with a lot of volume without making them prohibitively heavy and expensive.”

COSMOS EARRINGS AND RING of sterling silver and leather, 2018-2019. Model: Marina Boswell. Photographs by Walter Colley Images.

PAPER RUNWAY PIECE of paper, 10.2 x 487.7 centimeters, 2018. Model: Marina Boswell. Photographs by Walter Colley Images.

Krapf’s forms are sometimes drawn directly from nature—leaves, petals, or, on a more micro level, the double helixes embedded in the DNA of all living things—but he prefers for these forms to emerge organically in the studio. “I’m not a very conceptual person,” he says. “My work is quite minimalistic. It’s really just about the material and the form and the movement... I tend to design best through experimentation. I may do sketches and have a basic idea beforehand, but it usually changes and evolves as I make samples and try things out.”

In terms of materials, he also keeps his palette relatively simple. “For the most part, I stick to silver, gold, and platinum. I like highlighting the metal and am particularly interested in surface finish.” The pieces that incorporate stones often do so more as accents than as features, as in the aforementioned black diamonds. “I’ve been starting to experiment with stones. I don’t do it in most of my work yet,” he says. “I like using stones that have some interest just on their own. A lot of what I’ve used has been concave cut stones. I have an aquamarine pendant that’s also concave cut, but the stone itself was just beautiful.”

Another creative aspect of anticlastic raising is that artists often fashion their own tools in order to achieve specific results. This especially applies to the sinusoidal stakes, the snakelike metal tools that determine the parameters of the perpendicular curves. “I’ve done a little bit of milling and lathe work to make some dies. I’ve also experimented with having them 3D-printed in steel,” says Krapf.

“For different pieces you need different amounts of curve both the axial and the radial curves... I just bought a plastic 3D printer. I’m hoping that I can print out some sort of filament that’s strong enough, and that I can get more precise shapes and tools that way. We’ll see.”

Although he is forging his own path as an artist, Krapf credits his mother, Barbara Heinrich, as both an inspiration and a guide. “My business model is based on hers, we do all the shows together, and she’s a great sounding board in general when I’m trying to figure out a piece on either a technical or design standpoint.”

As of this fall, Krapf is enrolled in the MFA jewelry program at Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia. “I was attracted to the idea of having a couple years to play and experiment, and to be in an environment of young, creative designers, but also in a structured environment with deadlines and design parameters,” says Krapf. “I feel I need a certain amount of pressure to produce my best work. Part of my goal was just to give myself some time to develop my line, to branch out a little bit more.… I’ve started to find my own voice within anticlastic by breaking it apart and combining elements and soldering, doing the two-tone work, and adding gemstones.”

WAVE CUFF of eighteen karat gold and black diamond, 4.0 x 5 . 5 centimeters, 2020. Photograph by Mark Nantz. FLOWER PENDANT of eighteen karat gold and fantasy cut lavender quartz (cut by Darryl Alexander), 4.7 x 4.7 centimeters, 2022. SPIRAL EARRINGS of eighteen karat gold and black diamond, 1.5 x 4.5 centimeters, 2020. Photographs by Timo Krapf.

Like many other artists of his generation, Krapf is cognizant of the ways technology is reshaping the artistic landscape, but he sees this as more of an opportunity than a threat. “I haven’t experimented much with AI,” he says, “but I don’t see why not. I think it would be cool to see what it comes up with. Maybe it’ll be nothing, but maybe it’ll at least spark an idea and I’ll be like, ‘Oh, that’s cool.’… But I think that there will always be a value placed on handmade art. And I don’t see that going away.”

Ironically, as the first digitally immersed generation begins to reach middle adulthood, it’s possible that handmade objects will become even more sought after, in part because they forge the connections that people increasingly crave. “I was talking to another jeweler recently, Baiyang [Qiu], and she was saying that currently one of her strongest markets is people just aging into their early 30s,” says Krapf. “In our field, the personal connections are important, whether it’s through the trade shows or going and visiting the galleries… There’s a lot of trust involved,” he adds. “Going to shows and seeing people light up when they see a piece, or be really interested in the technique—that’s what gives me the energy to make more work.”

Krapf also looks forward to a time when he can pay forward the gifts he’s received. “I think part of my way will be to continue that legacy and impart that knowledge others.” In this, he points to Michael Good as an example. “That’s an important aspect to him, just sharing and giving to the wider community. …Part of my duty will be to continue that on when he no longer can,” he says.

“I’m an artist, but mostly I’m just a maker,” he adds. “Honestly, bringing a little peace and joy and beauty into the world—that’s enough.”

SUGGESTED READING

Kulpa, Shawna. “Timo Krapf. A Trip to Remember.” MJSA Journal, August 2019: pp. 52–53.

Newman, Renée. “Metal magic crafted using anticlastic raising.” Jewellery Business, March 3, 2023, https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/metal-magic-crafted-using-anticlastic-raising/print/.

Patrich, Christine. “Anticlastic Forming Techniques.” https://www.ganoksin.com/ article/anticlastic-forming-techniques/.

Updike, Dave. “Barbara Heinrich. A Delicate Balance.” Ornament: Vol. 39, No. 4, 2017: pp. 30-35.

David Updike is director of publications at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. He has contributed numerous articles to Ornament over the years, including exhibition previews and reviews, and profiles of artists such as Namu Cho, Barbara Heinrich, Shana Kroiz, Holly Lee, Michael Manthey, Rebecca Myers, and Wendy Stevens. His deep interest in the arts expresses itself in each article, providing context and texture that gives valuable insight into the work he covers. In the last issue of our fiftieth anniversary, he delivers an exploration of the life and growing career of Timo Krapf, Barbara Heinrich’s son and a highly capable metalsmith in his own right. Seven years after writing Ornament’s cover article on his mother, he’s excited to see how Timo has developed his own artistic voice. Just starting his first semester at the Savannah College of Art & Design, Krapf and Updike met at an opportune moment.